by Jessica Handler

I have become, at fifty-three, a full-grown person. Two years ago, I stepped into the role of midwife to my mother’s death. I chose it. She was with me when I began. I would be with her when she ended.

Lung cancer had colonized her brain, her spine, her right hip and shoulder. Where did this begin? My father smoked, a lot. My mother smoked, very little. My parents and little sister lived fewer than ten miles from the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station on the morning that the reactor experienced a meltdown in March, 1979; I was away at college. Mom refinished furniture for a hobby, breathed the fumes, handled the toxins. After my father was gone from her life, her late-in-life boyfriend smoked. Where did this begin? Everywhere and nowhere.

“So this is what happens when you have six kinds of cancer,” Mom said the first time she fell. She said it again the first time she couldn’t stand unaided, and the day she threw up the crème brûlêe.

“It’s just three kinds of cancer,” I said, bringing her ginger tea to the table. We laughed, a little. We are dark-humored, and fluent in the language of terminal illness.

My mother had three daughters, of whom I am first and last. Susie has been dead for forty-four years, Sarah for twenty-one. Susie developed leukemia when she was six. I was eight. She lived less than two years. Our little sister Sarah lived with a rare blood disorder and died as a young woman. Mom and I spoke of them often. Often we spoke of them without words.

I told my sisters’ names to Y., our favorite nurse’s aide. “In case she’s looking for them,” I said. For dying people, past and present run together like chalk drawings in the rain. “She was calling for Susie yesterday,” Y. told me. I wondered aloud if Mom was troubled or frightened. “Not at all,” Y. said, relieved to know who my mother had been trying to find. “She was looking out the door, like she was calling in a child from playing.”

My heart broke.

•••

Some mornings I woke in my mother’s bed. Others I woke with my husband in my own bed, ninety-four miles from hers. There was a moment every morning when I didn’t know where I was.

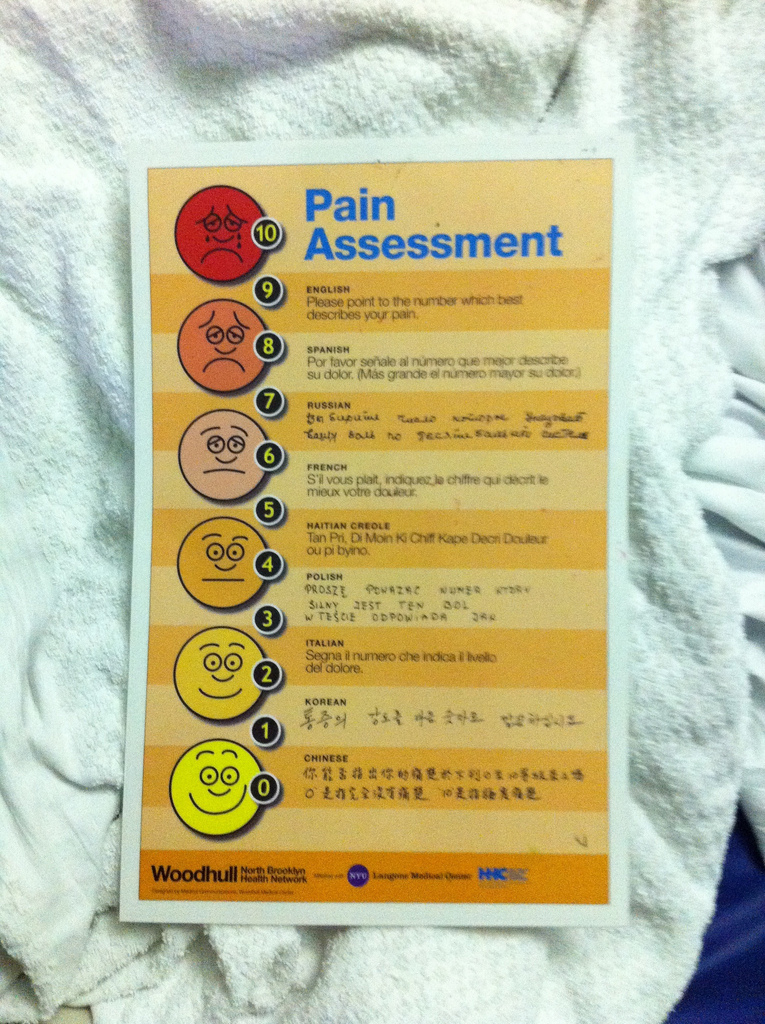

Mom’s pain was usually a two or three. On the Wong-Baker FACES™ pain scale chart, that’s somewhere between a smiley-face with barely knit brows and a smiley-face that appears to have something serious on its mind. The zero quantity of pain-free is represented by an untroubled smiley face with a touch of crazy-eyes. Neither Mom nor I reached a ten, the greatest level of pain. Ten is a crumpled, desperate face shedding drops that could be sweat or tears. Or blood. Her oncologist told us we were lucky.

My pain would hover at five, if pain scales measured the heart. I dreamed that it was me on the blue plastic draw sheet the nurses used to lift her. At the grocery store, I got lost. Which aisle has the cranberry juice? Does Mom have English muffins? This grocery store is in my city, not hers. I’m stocking my kitchen one week, hers another. I don’t want English muffins. I don’t want juice. I have lost fourteen pounds in the last two months. My always-slender mother wasted away. She weighed so little that I could lift her like a toddler. From the bed to the portable toilet, to the wheelchair, to the piano, to the bed.

•••

When I was a little girl, I drew pictures of birds and of girls. I couldn’t draw faces, so I put bird heads on girl bodies and made bird girls. I concentrated while I drew, singing a two-note song to myself, sustaining what I’ve come to understand as a meditative state. What am I focused on now, watching my mother’s face and seeing my own in hers? The bird-girls of my childhood drawings never flew. They went to work and ate and played and smiled their giddy smiles with beaks. They had expressive eyes.

Before my mother flew, before she closed her eyes and dreamed morphine dreams, our eyes locked over the commotion; so much to say, and nothing to say. We spoke without opening our mouths. We spoke without words.

•••

Mom died in her bed at home. She was seventy-eight. Hers was what hospice will tell me is a good death. A great death, the social worker will call it.

Several weeks earlier, to a nurse, a visiting friend, a relative—I no longer knew, everyone seemed interchangeable but my mother and me—I spoke for Mom on her behalf, even though she was right there in the living room with us, in a wing chair reading about Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell. I spoke as if she weren’t there. “I don’t think Mom will want that,” I’d said, about a sandwich or a painkiller or someone’s insistence that she go outdoors in the wheelchair she loathed. Mom looked up from her reading.

“I can speak for myself.” She was smiling, but I’d hurt her feelings.

Drawing her out, I toyed with grammar, a subject that entertained us both.

“I’ve made you object and subject,” I said, “so what’s the verb?”

“Am,” my mother told me. “The verb is ‘I am.’”

•••

On what would be the last night of her life, I fell asleep just after midnight, curled up beside her. When the nurse woke me, I was surprised by my calm. But that night, we were doing nothing but waiting, my mother and I. She had been on morphine for two days, bitter pills the nurse slipped under her tongue. Mom winced when she tasted them. She hadn’t spoken for two days, and then only a whisper: “I love you,” to Y., who had been part of her life for nearly a year, who climbed into the bed with her that morning to hold her and weep. When I stood beside the bed and asked Mom to rest, to take it easy, she mouthed, “I will.” I told her she’s my favorite mother. She smiled. I’ve told her that for years. Two nurses rolled her like a log and changed the draw sheet. We had a hard night. The oxygen she never used, never needed, became urgent for the first time the night before when Mom suddenly couldn’t catch her breath. I rolled the blue O2 machine from where she’d secreted it behind a nightstand. The evening assistant helped her with the cannula. “Do you want me to call hospice?” I asked Mom. She nodded, taking in the canned air.

At one in the morning, I sat cross-legged on her bed, holding her cool hand. I thought about how death is the exact opposite of birth. An obvious cycle and a thought not original to me, but I’ve never had a child and never witnessed a human birth. There was no sweat, no blood, no sound but Mom’s subtle breathing, arrhythmic and gentle. Her bedroom smelled of lavender from the bushy plant on the patio and from her hand cream. I held one of her lavender sachets to her nose. She grimaced, then relaxed. “Tell her what you’re holding so she doesn’t startle,” the night nurse told me. I did, then held the sachet to Mom’s face again. This time, she was calm.

The night nurse had woken me, saying barely audibly, “It’s time.” Time for what, I wondered, thick with sleep, then saw where I was, that my mother’s hand was entwined with mine. I was neither anxious nor weeping, not begging Mom to try and live one more day. There’s a falsehood in that statement: I was anxious. I lived with a low frequency of anxious for two years. I didn’t want her to ever die, to leave me. There was not one thing that I could do to change our course.

I asked the nurse to tell my husband, dozing in the den. She vanished, returned with him, tucked a chair behind him. We focused only on Mom. Her breathing slowed; her apnea grew longer and longer. She stopped. I looked up, gestured to the nurse. I remembered her name: M., from the compassionate care team, the end-of-life, round-the-clock team. She held her stethoscope to my mother’s chest, my mother skinny and sleeping in her white waffle-knit long sleeved t-shirt. M. shook her head, told me she’s still with us. Mom took another short breath, shallow, a surprise to me, and then she was empty. As empty as an overturned glass. M. flicked her penlight on and leaned into Mom, lifting an eyelid. She shone the light, closed Mom’s eye, and said, “She’s gone.”

We took from Mom’s pinky finger the silver and jade ring that my grandfather made, and I put it on my own.

•••

Full grown comes and goes with me. I don’t feel grown, and then I do. There is no choice. I wear the ring, and I feel my mother holding my hand. I hear her voice, flying just outside the scrim of my world. “I am,” she says. You are.

•••

JESSICA HANDLER is the author of the forthcoming Braving the Fire: A Guide to Writing About Grief (St. Martins Press, December 2013.) Her first book, Invisible Sisters: A Memoir (Public Affairs, 2009) is one of the “Twenty Five Books All Georgians Should Read.” Her nonfiction has appeared on NPR, in Tin House, Drunken Boat, Brevity, Newsweek, The Washington Post, and More Magazine. Honors include residencies at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, a 2010 Emerging Writer Fellowship from The Writers Center, the 2009 Peter Taylor Nonfiction Fellowship, and special mention for a 2008 Pushcart Prize.

Follow

Follow

Thank you. So beautifully written. So well said.

Love this piece. Thank you for inspiring me (yet again).

Jessica – Thank you. This brought back the profound combination of love, loss and acceptance that I’ve experienced – right there with you. Loved “chalk drawings in the rain”

This is a beautiful and wrenching essay, inviting the reader to nod in recognition, smile, mourn, wonder, and, most importantly, to inhabit the relationship between two people who love each other so very much. In this essay I recognize moments from relationships in my life, small and important moments that are hard to describe, hard to tell as story. Here these moments are articulated, illuminated, given their proper place. Thank you.

Wow.

Your work helped soothe my memory of my mom’s 1985 demise. Bless you.

“Sad is the deep person’s happy.” So as I sit here, saddened to the core by what I just read, I am, at once, happy. There is such beauty, such insight, such vividness portrayed in this essay. I find it calling to mind images of me holding my grandmother’s hand. How shocking it is to one day find the proverbial shoe on the other foot. Where once she protected me in the clasp of her hand, I now protect her. For me, she kept me from getting lost. For her, I keep her from falling down. Bittersweet and poignant.

So touching and lovely

Wow – I am so moved that this piece touched so many people. That’s the thing about writing well about loss – our stories are our own, but there’s such resonance when they make an impact. Thank y’all so much for shouting back. If you liked it, letter others know, and that will build more community for FGP!

I expected to cry. I did not expect to cry so deeply. This is beautifully written. The social worker said your mother’s was a good death. What I admire most is the courage and love with which you witnessed her passing. That is a good life.

Beautiful,Jessica. Your words bring comfort to so many~ Thank you for sharing such an eloquent and intimate essay.

This is an absolutely stunning essay.

Dear Sweet Jessica,

I am astonished by the generosity of this vivid, powerful essay. Thank you for writing it. The way you summarized the “extent” of your familiarity with death was so powerful—it gave me the courage to read the rest of this daunting and haunting tribute to grief itself. I am humbled yet inspired by your bravery to write about this so soon—which proves that writing can be one of the most exquisite of healing arts.

I am a daughter and a mother. Reading your beautiful piece – simple and yet profound – leaves me feeling my heart tugged in both directions. I have, thankfully, not yet had to endure such a loss; but just the thought of it, made tactile and piercing by your story, is enough to bring tears to my eyes. Beautifully written. I’m sorry for your loss.

Thank you for being so candid, Jessica. The passing on the pinky ring was so poignant. When my mother was dying of cancer, i crawled into her bed and got under the covers with her. We laughed and talked about nothing that was everything.

“midwife to my mother’s death”… I love that phrase. I became a grown up at 50. Now, I’m 8, having started the count over again AM (after Mom). Thank you for a marvelous, truly heartfelt read.

A beautifully honest and emotional piece, one that I could relate to after being with my mum as she passed away last year. At 26 I feel I have been robbed of so much time with mum but take some comfort from being there to make her passing as peaceful and loving as it could be

Really, really wonderful. Every note is true.

Dammit Jessica Handler, you made me cry. It was totally worth it.

Thank you, this was moving. My mother died at home a year after being diagnosed with Pancreatic Cancer and I’ve always been conflicted about the notion of a ‘good death’; but your essay has a tone of peace and serenity (for me at least, maybe its my mood)that makes me think perhaps this is as close to death being ‘good’ as one can hope.

Beautifully written and true. Thank you.

Glorious piece of writing. The depth of suffering so palpable, an essay to be cherished, read, and re-read.

I’m a daughter with an aging mother, and without sisters or children, so I felt a certain kinship. To adequately express how this essay soars, how the emotion clenches, how the chi of our humanity as women of finitude seems impossible. But there it is, my attempt to tell you how viscerally this piece matters to any of us who have lost, or will lose, a beloved parent.

This is a beautiful narrative. Sometimes we can’t make the decisions we want to make, and I am so glad you were able to spend this precious time with your Mum

Wow, this is stunning! And that you wrote this so shortly after her death is beyond amazing.

Thanks, Jessica.. While my mom suffers from Parkinson’s with dementia, not cancer, so much of what you said rings true. Thank you for putting so many of my feelings into words. I can only pray that her death will be as peaceful as your mother’s. Never easy though.

This is exquisite. I am deeply grateful that you are willing to share your journey with the world. Thank you.

This is a beautiful essay. Remarkable. I just ordered one of your books and am getting the other at the library.

Thank you so much!