By Donna Steiner

I.

New snow on top of the old makes the yard look curvaceous, bundled-up, like a new layer of insulation batting has been laid over the bones of old architecture. In the air, glitter, flakes blowing off rooftops, snow chipping and rising off its own surface. The yard, up close, is a sheet of crystalline alphabets, a cold, alien Braille—a version that disappears if you touch it.

Sometimes, when the sun shines on freshly fallen snow, it’s hard to look outside; I find it painful to keep my eyes open. I have to squint or use my hand to shield my eyes or, more wisely, put on sunglasses. In the morning, when I check the window fresh from sleep, my glasses aren’t handy, and so I look out and see a snow-globe scene, a world of swirling, sparkling snow, sun glaring off all surfaces with an intensity that makes me turn away. Snow blindness—photokeratitis—is caused by the eyes’ exposure to ultraviolet rays reflecting off snow or ice. I’m in no danger unless I wander wide-eyed outdoors for hours without sunglasses, but I learn through a little research that if you’re ever lost in the winter wild without sunglasses, you can fashion a functional set of eyewear by cutting narrow holes in a bandana. Inuits used caribou antlers, creating goggles by carving slits in the antler and securing them to the head with sinew.

Today I’m hunkered down indoors, in need only of reading glasses, puttering around my study looking for something to occupy my thoughts or my hands or my time. While half-heartedly dusting some bookshelves, I come across a treasured gift from my grandmother, a small, leather-bound book labeled DIARY 1947. I don’t remember how it came to be mine, but I think my grandmother gave it to my mother, and when my grandmother died, my mother passed it on to me.

If my facts about my grandmother are accurate—and there are plenty of reasons to believe they may not be, including family lore about her birth certificate being altered by a priest, presumably so she could get a job at an early age—she was born in 1910, which means she was thirty-seven when she wrote in the journal. She was widowed at thirty-four, and when I first saw this book, I had hopes that I’d glean some insight into what her life had been like, how she’d coped with the sudden loss of a beloved husband, how she’d raised three children on her own. Instead, I found listings of celebrities my grandmother saw on her frequent trips to New York City from her home in New Jersey.

As I flip through the diary’s pages, I realize I’ve already made a factual error. The book didn’t belong to my grandmother, at least originally. My mother bought it for herself as a teenager. She made a few entries—very few—but one clearly says “I bought this diary today.” On March 3, 1947—a Monday—my mother went with her friend Marie and purchased a book that she intended, I surmise, to regularly write in. There are exactly five entries made by my mother. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, were made by my grandmother. I don’t know if they agreed to share the book, or if my mother lost interest and my grandmother decided to put the diary to use. My mother’s concise notations are here, in their entirety, complete with her idiosyncratic errors:

Today after school I went on the ave. With my girlfriend “Marie.” I bought this Diary Today.

“My Birthday.”

I went to my aunt’s New Year’s party. Went to bed 4: o’clock. Sleep there all night.

Today I went to New York and I saw Jimmy Stewart who was guest star on the broadcast “It Pays to Be Ignorant.”

Went to girl scouts. Met a new girl named Pat.

From these notes, all made, presumably, when my mother was about thirteen or fourteen years old, I learn she had a few noteworthy female friends. She was a Girl Scout. She was not accustomed to staying up late. She once attended a radio show featuring Jimmy Stewart. What I can’t discern is any evidence that she missed her father, that her mother or she struggled at all with his absence, that she had two younger brothers, that she ever attended school, that she liked boys, that she lived in Jersey City. There is no mention of emotion, of ambition, not even a reference to the weather. Her most common verb is “went.” She went places.

(My favorite photograph of my mother is in black and white. She’s just a girl, maybe ten years old, and she’s somberly staring out a train window, on her way to the city. She’s wearing a white dress and white anklets, and has an adorable haircut. It looks like she has a pencil case on her lap, and she appears to be deep in thought. The picture fascinates me, feels historical, weighty, relevant, like if I study it long enough I might see myself as a flickering idea in the back of my mother’s mind.)

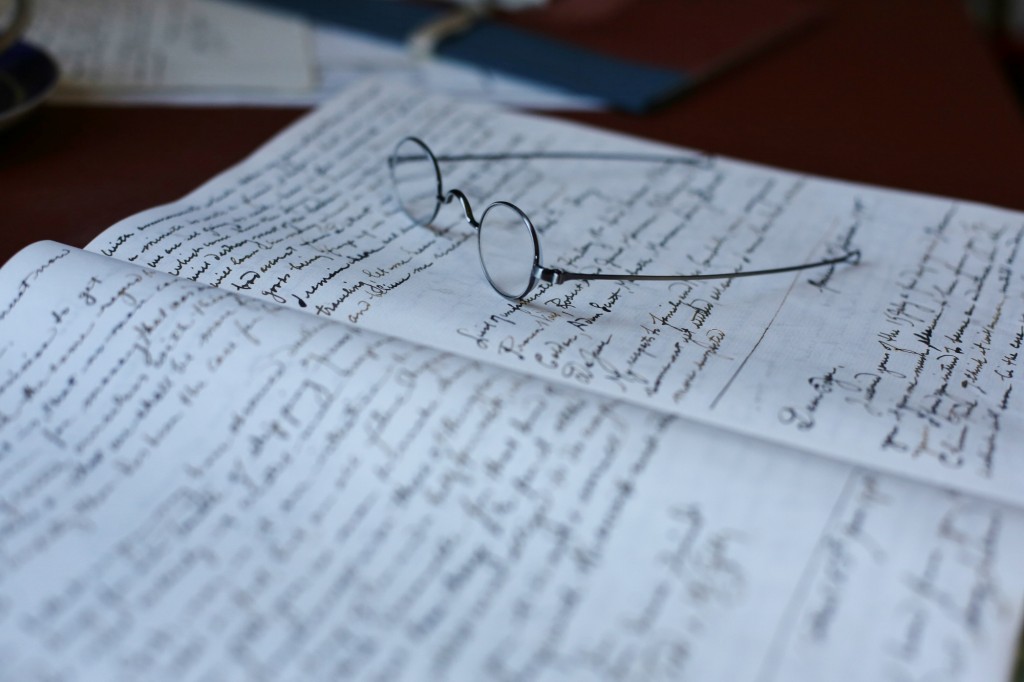

My grandmother’s entries are numerous and her handwriting flamboyant. While my mother’s cursive style is tight and her words huddle together, my grandmother’s script has a lot of air in it, lots of curves. She pays no attention to the lines on the page and often slants her entries as though the words are climbing steeply uphill. Representative entries from my grandmother:

I went to H.R.C. to Christen my Nephew Victor. I stood up for him. We had a Delicious dinner and at night we had a party for family. Had a swell time.

Went to New York with Dorothy. Went to see Ingrid Bergman. Manager let us in. Saw Last Act of Play Joan of Lorraine. Swell.

Saw Lucille Ball. She is one swell person.

Went to New York. Saw Quick as a Flash. Saw the Shadow (great) then went to Kate Smith Show. She sang all Irish Songs. She certainly is swell.

Dot had a party. 7 girls came. Had a swell time. Made some mony. Got some nice gifts.

A few notes:

- I’m not positive as to what H.R.C. stands for, but I think it’s probably Holy Rosary Church, which claims to be the “oldest Italian Roman Catholic church in New Jersey” and was just a few blocks from where my grandmother and her children lived.

- Dorothy (Dot) is my mother.

- During the thirty years I knew my grandmother, I never heard her use the word “swell.”

- Lest one think my grandmother found everything swell, I should point out that interspersed among the more positive entries—which are the bulk of her notations—are what she calls her “crumb lists.” These are stars who did not stop and say hello, sign autographs, or even wave to their fans.

- There’s no entry on my birthday. How could there be? I wouldn’t be born for twelve more years. Still, the blank page feels disturbing.

- There is no entry on May 8th, which would eventually be the date on which my grandmother died—forty-three years in the future. That, conversely, seems fitting.

- At the end of the book is a page for addresses. There are seven entries: women named Marie, Catherine, Theresa, Betty Anne, Dolores, Rita, and Mrs. Prichard. There are no addresses for men.

- My grandmother wrote with a fountain pen. Several fountain pens, actually, with inks in various shades of blue or black. Just a few entries are in pencil, with inked notations adjacent to them, like this:

Mary Martin (in pencil) swell person (in ink)

- Both my mother and grandmother seem to have abandoned the diary after October 9th. On that day, in 1947, they attended the premier of the play High Button Shoes, where they saw in attendance Frank and Nancy Sinatra, Danny Kaye, and Doris Day, among others. My grandmother’s assessment of the show: Very Good. I’m not sure if very good is better than swell.

(My favorite photograph of my grandmother appears to have been taken in a studio. She is wearing a white dress with dark stripes on the sleeves. It is fitted and stylish, and my grandmother—whom I knew as a short, plump, elderly woman—is slender and stunning. Around her neck are pearls and she’s wearing a trendy hat and white gloves, clutching a small purse. Her hair appears to have been done professionally. It is, in other words, a glamorous shot, dramatically different than the Polaroids and faded photographs that show her sitting in a lawn chair wearing white Keds or clustered with one or another of her sisters or grandchildren. Although she is smiling in every photograph I have and, in fact, was often laughing and was, in fact again, considered the life of any party, I can’t help but see her, in these photographs and in my memories, as lonely. Perhaps it is because she spoke, aloud, to her deceased husband every night in bed. Perhaps it is because she lived considerably longer without him than with him. Or perhaps photographs are mirrors, and I see some fundamental loneliness in her that is simply my own default nature.)

II.

Before I learned to write, I’d implore my mother to read my scribbles and tell me what they meant. I’d take a pencil or crayon and scrawl something that resembled, I thought, actual handwriting. “What does it say?” I’d ask, holding my work up to her. My mother would make up a story, tell me what I’d written, and I’d listen, rapt, impressed with my own startling creativity.

I didn’t stop there, however. I tried to read meaning into everything. During breakfast I’d take a few bites out of a slice of toast and hold it up to my mother as though the bread were a sheet of paper. “What does it say?” I’d ask.

“It says ‘I am a hungry tiger,’” my mother would respond, absent-mindedly.

Looking up at the clouds, I’d ask what they said, and she’d read me the clouds’ message. If I had scratches on my leg, I’d ask her what letters the scratches made. When my father told me stories at bedtime—stories that often featured me as the protagonist—I didn’t understand that he had made them up; I didn’t know yet what it meant to imagine. When a little girl named Donna was able to ride a flying horse in those stories, I thought it was magic not only that a horse could fly, but that in some parallel world there existed a girl with my exact name, my exact age, with a family just like mine, with long hair like mine. I wasn’t sure how my father knew about her, but I didn’t doubt the veracity of that knowledge.

I still try to unearth meaning wherever I look. Whether it is a snow-covered field, or a book written in by a woman gone for two decades, or whether it is the body of a lover that I am studying with my fingertips, I am attempting to read a text. That’s a common tendency—as is trying to find meaning in erasures, blank spots, in what isn’t said or written.

I have an envelope of “skeleton leaves,” which are made by soaking actual leaves—in this case, those of a rubber tree—in bleached water for a few weeks. After that lengthy bath, someone hand-rubs the green off the leaves. This is a delicate process, as the leaves’ veins can easily tear. I don’t know who discovered this process, or exactly why anyone does it, although it appears to be a kind of art. But a friend gave me the packet, imported from Thailand, and I love the gift. I study the skeletons with my eyes, with my fingertips, under which they feel like rough paper. Human fingers are hypersensitive; scientists believe we can detect a bump 1/25,000 of an inch high. I’m doubtful about my own sensitivity, but I can feel a leaf’s midrib and its veins, and the entire remnant is surprisingly sturdy. I could tear it, but I’d have to make an effort. Inflicting damage would be intentional rather than accidental, knowledge that allows me to study the skeletons without worry.

I have no memories of my grandmother in winter, I have no memory of her in New York City, I have no memory of her beyond being mine—my grandmother. When I picture her, the sun is always shining, she is always tan and freckled and sleeveless, her shoulders smell of Noxzema, she is laughing. I hang on to this diary the way one covets any treasure, storing it away for safekeeping, taking it out every so often, blowing dust off its leather cover. Sometimes I use the book as a kind of talisman or oracle, deciding that whatever page I open to will mean something, give me some kind of important message to live by.

Today when I open the book to look for a message, both pages are blank. But I can see through the blank pages to the writing underneath, as though looking through skin and seeing blue shadow veins beneath. It is a list of celebrities, of stars, and I can see, if I squint, the last words she wrote in her loopy, lovely penmanship: It was Swell.

•••

DONNA STEINER’s writing has been published in literary journals including Fourth Genre, Shenandoah, The Bellingham Review, The Sun, and Stone Canoe. She teaches at the State University of New York in Oswego and is a contributing writer for Hippocampus Magazine. She recently completed a nonfiction manuscript and is working on a collection of poems. A chapbook of five essays, Elements, was released by Sweet Publications.

Follow

Follow