By Carol Paik

I had been thinking a lot about paper—specifically, about how much of it I throw away and how wasteful that seems—so I decided to try making some of my own. This happens to me from time to time: I become overwhelmed with guilt about the garbage I generate and I then think, well, it’s kind of pathetic to just feel bad, surely, there’s something constructive that Can Be Done. At other times when I have felt like this, I have taken up yogurt-making and bread-making, not for health reasons or because I’m preservative-phobic—quite the contrary, I’m all in favor of preservatives, at least in moderation—but because it seems that yogurt containers, bread bags, and paper are the three things I throw away in unconscionable quantities and I have this vision in my head of the Pacific garbage patch that won’t dissipate. The vision won’t dissipate, and apparently neither will the garbage patch.

Making paper is actually fairly easy. (As it turns out, so is yogurt-making, if you have a yogurt-maker, whose sole function is to control temperature; and so is bread-making, if you own a bread machine. I probably don’t need to point out that purchasing these appliances, compact as they are, negates the whole purpose of yogurt/bread/paper–making, which was to reduce my carbon footprint. Also, they’re only easy if you’re content, as I am, with relatively pedestrian yogurt/bread/paper.) When I first read about papermaking, it sounded really hard. It sounded like it involved roaming around in the woods pulling up fibrous grasses and roots with gloved hands, pounding them with a wooden mallet or something equally unwieldy and full of splinters, or maybe stomping on them in a vat. It sounded laborious, in a tedious way but at the same time, in addition, as if it involved some mysterious technical dexterity, some sleight-of-hand. But really it’s easy. And it does help if you buy Arnold Grummer’s basic paper making kit, available online for about $30.95, which consists of a “pour deckle” (a rectangular wooden frame), “papermaking screen” (a piece of mesh), a sturdy plastic grid, a wooden bar, and a sponge.

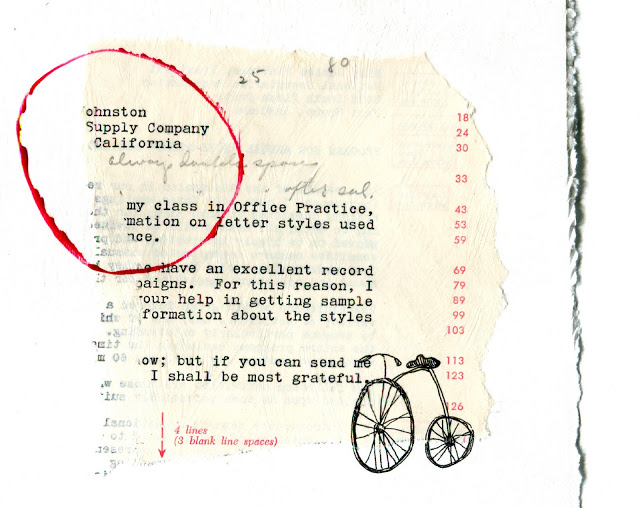

And while you can certainly go out into the fields and gather plants and boil them and pound them and boil them again until the fibers lose their backbone and will, all you really need, and what the kit recommends, and the whole reason I wanted to make paper in the first place, is garbage. You take your paper garbage. You take your old copies of Fitness and More (for Women Over 40) magazines that you got free for running the More half-marathon last year and whose exhortations and promises now weary you; you take bank statements and credit card bills (from before you went paperless); letters from your kids’ high school administrators about what they’re doing to prevent sexual assault; requests for money from so very many worthy charitable ventures, so many that you couldn’t possibly give to them all. In particular you take your drafts of the young adult novel you’re no longer even remotely interested in finishing.

You take it all and you energetically tear it all up, first lengthwise and then crosswise, into jaggedy half-inch squares.

You put a few handfuls, or about as many scraps as could be puzzled into a letter-size sheet of paper, into a blender, add two cups of tap water and push “blend.” The instructions say quite specifically that you should have a designated blender for this task. You shouldn’t blend paper and then expect to use the same blender to blend your smoothies. Making paper is a toxic endeavor, as scrap paper is laden with chemicals. One papermaking book I read suggested going to the local Goodwill or the garbage dump and finding a used blender, but I would be afraid of something electrical that someone abandoned at the dump so I went to the hardware store instead and bought the cheapest blender I could find, although it was kind of hard to find one that didn’t have fifteen different speeds. And of course that was frustrating, because the whole idea, remember, was not to buy another appliance! The whole idea was that I was going to be making something out of nothing, and making something out of nothing and reducing the Pacific garbage patch shouldn’t involve purchasing a brand new blender. So already, before I even started, I felt a little defeated and sheepish.

But anyway, you take your non-fancy, non-European blender and blend the paper scraps and water, and when you have a blurry mess (takes about thirty seconds) you pour it into the wooden frame, which you have submerged in a small tub of water. There’s a lot of sloshing of water involved in the papermaking process, so you have to put the tub of water in the kitchen sink. Many papermakers advocate making paper outdoors, but it was wintertime when I felt the need to make paper, so outdoors was not an option. It made me wonder, reading this advice, whether most people who make paper live in California, or Arizona, or some place idyllic and temperate, some place that isn’t where I live, some place that doesn’t have long, drawn-out miserable winters during which you sit indoors thinking about how your kids will be leaving for college soon and won’t need you any more and how you’d better come up with a new sense of purpose or at least some hobbies.

So you need to occupy the kitchen sink. If other people need to use the kitchen sink or the surrounding countertop area, this could pose a problem, especially given the toxic nature of what you are doing. But you don’t care what anyone else needs right now, because you are determined to create something today, today you are going to make something, you are going to make something out of nothing, and that is a worthy goal, and one that is worth occupying the kitchen for, and if other people want to, say, cook, or get a glass of water, or something, they’re just going to have to wait because you deliberately and considerately waited to do this until right after lunch after you’d cleaned up the dirty dishes, so that no one should really need this area for at least a few hours and it’s not really asking that much for them to go away.

And furthermore those people don’t need to hang around and silently and concernedly watch you blend scraps of garbage with water in a blender, either. They must have better things to do.

So, you can decide how uniform you want your pulp to be. You can blend it longer and have a very smooth pulp, or you can blend it less and have some identifiable bits of paper floating in it. This is one of the parts of papermaking that is up to you; this is one of the steps where you can express yourself. Making paper in a blender is not rote or mechanical. It is an art, and this is why: you can decide how long you want to push “blend.”

Once you’ve poured the pulp into the frame, it floats around in the water and you dabble your fingers in it to distribute it around. Once the pulp seems fairly evenly distributed, you slowly lift the frame out of the water. There is a piece of wire screening across the bottom of the frame, and the pulp settles on top of this screen and as you lift it from the water a layer of pulp forms there. You hold it for a moment above the tub so the water can drain out, and then you are left with a layer of pulp that, once dry, will be your new sheet of paper.

The very first time I did this, it worked perfectly, and the second and third times, too. The pulp lay even and flat across the screen and I thought, there is nothing to this papermaking business. Not only have I tried something new, I have mastered it! In one afternoon! The fourth time I did it, however, with all the confidence of the seasoned, the pulp clumped up. I had to re-submerge the frame and stir the pulp around with my fingers several times until the screen was satisfactorily covered, but even then the layer of pulp was lumpy. I thought, good thing this didn’t happen the first time, I would have given up right then. My initial taste of success was sufficient, however, to make me keep trying despite this setback—but when I kept stirring and lifting and the pulp still would not lie flat, I almost gave up anyway. Who wants to make paper. What a stupid thing to want to do. You can easily buy paper. It cost more to buy the kit and the blender than it does to buy like a ream of brand-new paper. What do I think I’m doing, saving the environment or something? Go through all this trouble, and for what? Take up this space, make this mess, spend this time and effort … for what? For whom?

After this little paroxysm of self-doubt, I reminded myself that I am far too mature to have tantrums, that I am capable of handling a little frustration. I got a grip and went online. And the internet paper-making community rose to my aid.

I learned, through my research, that the problem could be that the little openings in the screen were getting blocked by paper pulp, making it so that the water did not drain out evenly. The screen needed to be cleaned with a brush. After I cleaned the screen, the pulp did in fact lie more smoothly.

Once you’ve lifted the sheet of proto-paper out of the water, you have to remove it from the frame. The screen is held in place by a plastic grid, which is strapped tightly to the frame with Velcro bands. You put the frame on an old cookie sheet (which you will never again use for cookies), unstick the Velcro, and lift the frame off the screen. And there is the paper, perfectly rectangular, with softly ragged edges that give it that unfakeable artisanal look. You then place a sheet of plastic over it and turn the whole thing over. You try to squeeze as much water out of it as you can with the wooden block, and when it’s pretty well squeezed you sandwich it between two “couching sheets” (other pieces of paper).

Then the paper needs to dry. You press the new pieces of paper under a stack of books so that they dry flat. The drying is the only time-consuming part of the process. You have to wait overnight at least. After that you—or I, anyway—get impatient and leave the pieces out in the open to dry, and they end up drying curly even after all that time being pressed under books.

Once I get started making paper, it’s hard to stop. You tear up paper, you pour in water, you push a button, you pour the pulp, you lift the frame, you remove the new sheet of paper. You do it again, if you want to. If you want to, you do it again. It can take on a rhythm. The grating noise of the blender no longer bothers you. You can become a little crazed. Soon there are damp couching sheets all over the kitchen. But tomorrow, you know, you’ll have a satisfying stack of curly, bumpy paper to show for it.

The paper is not necessarily beautiful. Some of it looks a lot like dryer lint. Some of it looks a lot like garbage that’s been ground up and flattened—surprising! But some sheets of paper are delicately colored from the inks in the recycled papers, and some have little remnants of words in them from the bits that you decided not to grind too fine. Some have truncated Chinese character limbs from the chopstick wrappers I used. Some have shiny bits from the linings of tea bags. One piece has colorful threads running through it that I harvested from the bottom of my sewing basket. Once you get the hang of it, you can start throwing pretty much anything in that blender. Even before you get the hang of it. You can throw almost anything in there, and you never know exactly how it will come out.

I’ve heard that all the molecules in our bodies have been used before. It’s the same with the paper.

But papermaking isn’t really transformative. You don’t really make a beautiful thing out of ugly things. I was hoping that at least I was making a useful thing out of useless things, but that’s not exactly true, either. I don’t think I can use this paper to write on. I don’t think I can run it through my printer. But still, I have a stack of paper where before I only had garbage. That feels like some cosmic gain.

When I decide I’m done for the day, mostly because other people do need to use the kitchen, I wonder what would happen if I had my own papermaking studio. With endless space and time to make as much paper as I wanted. To make whole, huge, luminous, empty sheets, using frames that require the entire stretch of both arms and all my upper-body strength to lift. Maybe I would make paper all day. I read about a man who does that, a professional paper artist. The Library of Congress insists upon using his papers to repair their most delicate treasures. But I wouldn’t want to do that. I would get tired of it if I did it all day. I would hate the pressure I would feel from the Library of Congress to maintain my paper’s quality. And what would I do with all that paper? The Library of Congress couldn’t possibly want it all. It would accumulate in stacks, in various stages of dry and damp, it would rise in dense towers, my house would fall down, I would never be heard from again.

I learned in this process that paper is a relatively recent invention. It was only introduced to the Western world in the Middle Ages. I am trying to imagine a world without paper. What did people use to write on? There was vellum, which is not technically paper, as it is made from skins, not from the particular water-based process used for authentic paper. Mass-produced paper did not exist until fairly recent times. Before that time, how did people write? More importantly, how did they re-write? They couldn’t, I bet. They probably couldn’t have conceived of wasting precious writing materials on a shitty first draft. They would have had to know what they wanted to say, and they would have had to have been convinced that it was worth saying before they would even have thought of writing anything down.

I have a growing stack of my own paper now. Each sheet is crisp and substantial, like a very healthy kind of grayish cracker. I like to look at the sheets. Some of them are little collages in and of themselves, with random bits of color and texture that are visually and tactilely pleasing. But whatever beauty the paper possesses feels so accidental that I can’t take any creative pride in it.

I shuffle my stack. I deem paper-making, overall, a qualified success, worth repeating when the issues of More start piling up. But in subsequent paper-making sessions I have been unable to recapture the thrill—no, I’m not overstating it!—the thrill, the magic, of seeing a perfectly flat, unique sheet of proto-paper emerge from the bath. Every sheet I make now feels like a product of a process, with some luck thrown in, rather than of magic. But maybe that’s okay.

•••

CAROL PAIK lives in New York with her husband in a half-empty nest. She expects to turn fifty next week. Her essays have appeared in Brain, Child, Tin House, The Gettysburg Review, Fourth Genre, and Literal Latte, among other places. She recently wrote the screenplay for a short film, Pear, that won the Audience Choice Award for Best Short Film at the Sedona Film Festival, and will next be screened at FilmColumbia 2013 in Chatham, NY (www.filmcolumbia.com) and the Brattleboro Film Festival in Brattleboro, VT (www.brattleborofilmfestival.org). More of her writing at: www.carolpaik.com.

Follow

Follow