By Dina L. Relles

“Will we be tying your tubes during the procedure?”

I was sitting cross-legged on the sticky pleather—the doctor’s sterile office familiar by now—my hands clasped under my full belly.

Moments earlier, my weight gain, blood pressure, and a healthy fetal heart rate were all scratched in tiny illegible marks on my overstuffed chart. The nurse with a tendency to call me “hun” had taken her two hands and caressed my bump as she spoke softly of her own family. Three boys, like me. And she tried, tried for that fourth. Three miscarriages later—the last at twenty weeks—she knew it wouldn’t be.

“Do you want your tubes tied?” I looked up to meet the doctor’s expectant eyes. The question was not new. He or the nurse, sometimes both, asked at each monthly visit.

I had yet to answer.

•••

I once loved a man who kept coming back.

He’d show up at the side door of the seventies-style off-campus apartment in the Portuguese section of Providence. I’d let him climb the spiral staircase to my room in back, the one facing Ives Street, with the lone blue wall we’d painted together when our love was young. Back when we drank and smoked and snaked his shitty silver sedan up the coast over winter break, The White Stripes streaming through the speakers. Back when we jumped up and down on that old secondhand mattress on Williams Street when, wasted, he proposed marriage before we collapsed, slick with sex and sweat.

Years later, he’d show up in bars across downtown Manhattan. We’d drink together because that’s what we did, huddled at the bar or in some corner booth, our heads touching, our speech slurred.

We stood on the dark Soho street corner, embracing as the cab idled. I was already seeing someone else, but we kissed all the same, our mouths full of memory. As if we didn’t know how to part without it. The mere taste of his tongue made me think of the scar on my knee from that time on the car console just over the Arkansas border. Part of me cherished the memento.

“I’ll call you?” he mouthed through the taxi window.

“Okay,” I said. “Sure.”

•••

I’d already be under the knife—that much was clear. My babies only came out with the help of a surgeon’s hand. After forty-eight hours of labor and over four hours of pushing, my first son—a week late—still held on.

Now I was facing my fourth C-section. At thirty-five, with a husband of thirty-eight, I had plenty of potentially fertile years still ahead of me. And, the doctor warned, a fifth C-section would be unwise. A tubal ligation is the recommended course. He—everyone—assumes I’m done.

And probably, I am.

But some of us have a hard time letting go.

•••

There’s a bin under my bed that no one ever sees.

In it, a pair of socks with iron-on labels from an old summer camp beau, floppy disks with early drafts of college papers, locks of towhead blond baby hair, a burgundy waitress apron from a gig in a breakfast place fifteen years back.

There’s a box of decaying Godiva chocolates from a boy I dated in 1989. Midway through that year, he moved upstate and would send me letters on primary colored paper drenched in prepubescent cologne. I saved those too.

Affixed to a broken bookcase against the wall of my parents’ garage are index cards with phone numbers of old friends or lovers in faded Crayola marker. I haven’t called any of them in years; those aren’t even their numbers anymore. I don’t take them down.

There’s a pair of two-toned oxfords with frayed laces and eroded heels stashed in the corner of my closet. I keep shoes long past their prime; they’ve walked with me; their soles bear bits of where I’ve been. My shirtsleeves hang past my wrists, and I should get my pants hemmed, but I don’t. They drag in shallow puddles, soaking up the muddy moisture, and I take that with me too.

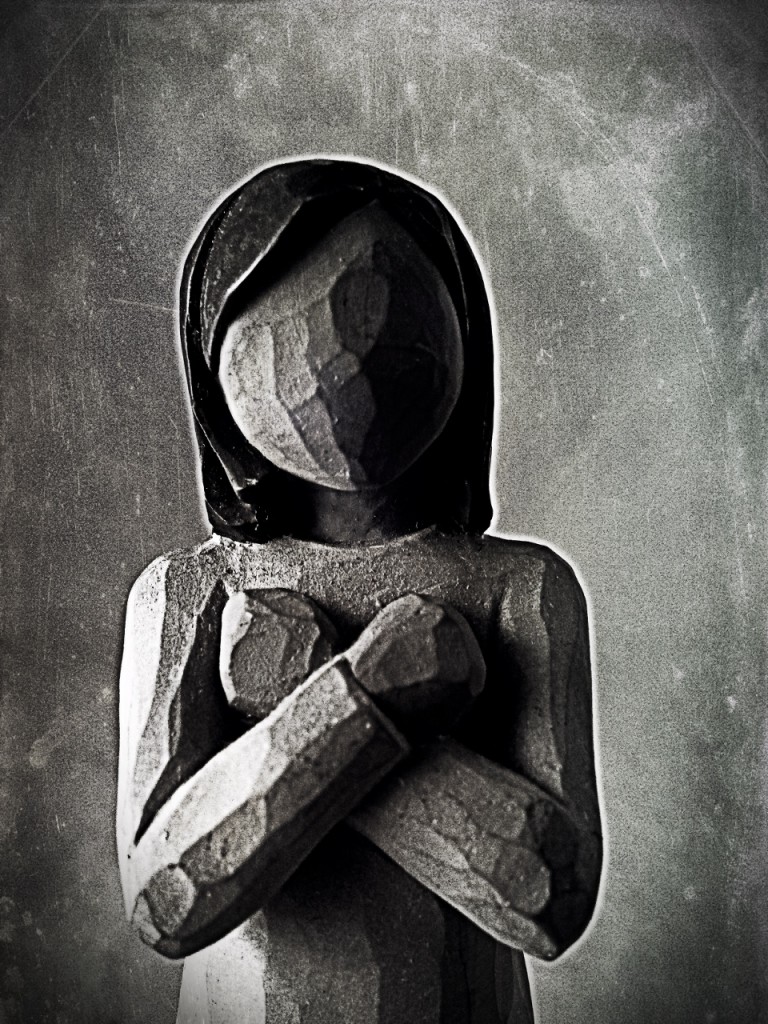

I’m heavy with the weight of all I hold onto.

•••

I went into labor with my third son four days before my scheduled C-section. I was tucking my older two boys into bed when I felt an insistent gush of fluid between my legs. Some frantic Internet research confirmed: my water had broken. I called my husband to come home, my in-laws to get the kids. Two hours later, we were walking to the hospital four blocks down the road.

By the time we reached triage, the contractions were coming fast and fierce. They only intensified as we waited for anesthesiology. Four minutes apart, then two. It took eight tries to land my intravenous line, my veins thin and resistant, my hands and arms bruised from failed attempts. Each time, the nurses would beg me to lie flat on my back. It was unthinkable in the midst of a contraction, as my body tensed and fought to push this baby out.

“It’s not fair!” I wailed again and again, thrashing my arms against the crinkly bed paper. All the labor pain was for naught—they’d be cutting me open regardless. But what I mourned most were the four days I expected him still inside me.

•••

Sometimes I try to trick time. I wake in the dark early morning, at three or four a.m., lengthening the days by stealing hours from the night. I am unwilling to let moments pass without living as many of them as I can.

•••

One day, I look up the definition of tubal ligation online and read that it’s a sterilization procedure, according to Wikipedia, “in which a woman’s fallopian tubes are clamped and blocked, or severed and sealed…”

My mind wanders to the days and weeks following my firstborn’s birth. “I’ll remove them for you in a single swoop. You won’t feel a thing.” My husband, a surgeon, stared disapprovingly at the Steri-Strips that still railroad-tracked my incision, over six weeks since the C-section.

“What’s the rush?” I countered. “They’ll fall off eventually.” I feared not pain, but a sense of loss. The tape residue on the backs of my hands from where they inserted the IV was long gone; my body was steadily shrinking as my son’s swelled—he had already outgrown all the newborn-size clothing.

The Steri-Strips, cruddy and useless, were all that was left of the lengthy labor and delivery, of the day that morphed me into a mother.

“A woman’s fallopian tubes are…severed and sealed…” I flinch involuntarily and close the computer screen.

•••

At my tenth college reunion, I pass the old dorm where, in room 150, we first made love. I close my eyes and linger there for a little, letting the wind whip my face, my feet unsteady. I force myself to feel back there—to remember the room, what I wore, how we laughed and worried we were doing it wrong. I try to conjure any scraps of conversation my imperfect memory will allow.

For a long time, on that date—of lost virginity to a lost love—I would carve out a few moments to recall whatever I could. Each year, it was less. Eventually May 8th came and went without me even noticing.

•••

I lie awake in bed and feel the flutter of the baby low in my abdomen. Soon my body will be emptied of another for good. I will the days before the birth to pass slowly.

•••

It’s not aging that fazes me; I’m not particularly attached to my youth. But it’s the letting go, the slipping away of anything I’ve been, known, loved.

Maybe if I carry enough with me through this life, I’ll move so slowly that nothing will change.

•••

My belly feels heavier this time, if that’s possible, my mood constantly shifting. Most of the time, I feel damn lucky. But tired, too, weighed down. Laden with another life.

For weeks, I hedged. I never felt uncertain of my answer, but the utter irrationality of it kept me from admitting it to myself, from speaking it aloud. One Tuesday, halfway through the pregnancy, I found the words:

“It’s the finality of it,” I start. “I’m just not ready to have my tubes tied, even though this is likely our last. So no.” My voice gains strength. “I can’t.”

•••

The rain pounds mercilessly on the roof, ricochets loudly off the metal gutters. It’s only three p.m., but the skies are black. My oldest son’s school bus turns slowly onto our street, delivering the last of my three children home.

I’ve collected the stray lawn chairs and trash pail lids from along the driveway, stowed them in the garage. I gather whatever I can, keep it close.

We are safe against the storm.

•••

DINA L. RELLES is a writer with work published in The Atlantic, Atticus Review, River Teeth, STIR Journal, Full Grown People, The Manifest-Station, The Washington Post, and elsewhere. A piece of hers was recently chosen as a finalist in Split Lip Magazine’s Livershot Memoir Contest. She is a blog editor at Literary Mama and is currently at work on her first book of nonfiction. You can find her at www.dinarelles.com or on Twitter @DinaLRelles.

Follow

Follow

I could relate to this so easily. I don’t like to let things go either. So many lines in this touched me when I read them. Beautiful. This is what memoir is meant to look like.

Thank you so very much, Kerry–what kind words. I’m so glad you could relate. Thanks, always, for reading. xo

Fertility and virginity and lost loves and fragments of memories…. “our mouths full of memory.” Oh, how you mine this decision to sever and seal, to cut yourself off from future life and lives. Aching and gorgeous, every line. Love it so much, Dina.

I wish I could cut your comments out and fold them up into little letters that I could stash away along with everything else I hold so dear. You always, always see straight to the heart of things, of me. Your words here are a gift; thank you for them, Daisy. xox

YOU are a gift! keep going….. birth that baby and more!

As someone who is seventy one years young who lay awake last night and walked through memories of all four years of college like it was yesterday, I can so relate to this piece. When I was recovering from my fourth C-section, my OB stopped by the house as I lay reclining contentedly on the couch with my newborn asleep on my chest. “Could I have just one more, I asked,” with a mischievous smile? “You’ll get over it in four or five months,” he assured me. I’m not sure I did.

Oh I love this comment so much–I imagine myself at seventy one feeling exactly the same way. People say you’ll know when you’re done, but perhaps some of us never really do…thank you for this.

Oh, this is beautiful Dina. I’m a saver too, a holder onto of things from the past. Nostalgia is my kryptonite but also my gift. I want to linger, to remember. I’m having a hard time feeling done with babies even though I pretty much know I am, and I can understand not wanting to be severed and sealed.

YES–I’ve come to believe there is a certain power in nostalgia. It’s a thread I keep coming back to in my writing–circling it and why it has such a hold over me. Ultimately, I think it has everything to do with deeply loving the time we have here on earth–not wanting to let any of it go. And yes…never severed, never sealed…Thanks so much for reading and adding your thoughts, Dana. xoxo

Just gorgeous. I once spent an entire plane ride trying to conjure up an image of every single person I have ever known and at least one memory with that person. I wanted to ensure myself that those who are long gone, for whatever reason, are still a part of me. I smiled the entire flight.

I love that so much. What a tremendous exercise! And in flight–where emotions run high (pardon the pun)…thanks for sharing this.

This is breathtaking, Dina. I have two boys and my husband is done, even as I long for the scent of newborn and the feel of them pressed into me, nursing again. I keep far too many baby clothes. And lately tears prick my eyes far too often.

I love your gathered memories here. Thank you for sharing. And I’m sending wishes that they’re always safe.

Thank you, dear Dakota. And I know exactly what you mean–I’m not sure I will ever truly feel done…

Beautifully written.

Thank you!!

Oh my gosh this was such an incredible read. I can’t remember when I was captivated by words like I was with these… Your vivid pieces of history, beautiful reflection and deep introspective thoughts on letting go moved me so deeply.

Thank you for this exquisite piece of work. Wow. You are SO gifted.

Thank you so very much, Chris. This comment warmed my heart. Too, too kind. xox

Boy, do I feel every word of this essay. You write beautifully about complex emotions that, for some of us, arise from the awareness of receding time.

Thank you so much, Kim. The awareness of receding time…yes…

This is beyond beautiful, Dina. The details themselves linger with power. So much to think on here — thank you for sharing such a beautiful story with us!

Thank you so much, Antonia–means the world coming from you. xo

Such a beautifully woven piece. Thank you.

How did I miss this? Dina, such excellent work as always.