By Reyna Eisenstark

A few years ago, my ex-husband C. (already my ex-husband of a few years) fell down in his living room and could not get up. He was eventually able to crawl to a phone and call 911, and he assured the cop who showed up that he wasn’t drunk. It’s hard to know what exactly the cop thought of him, a fifty-year-old man crawling around on his hands and knees in a once-beautiful house that had been gutted to its studs and that also included cages of parrots that may or may not have been squawking in panic.

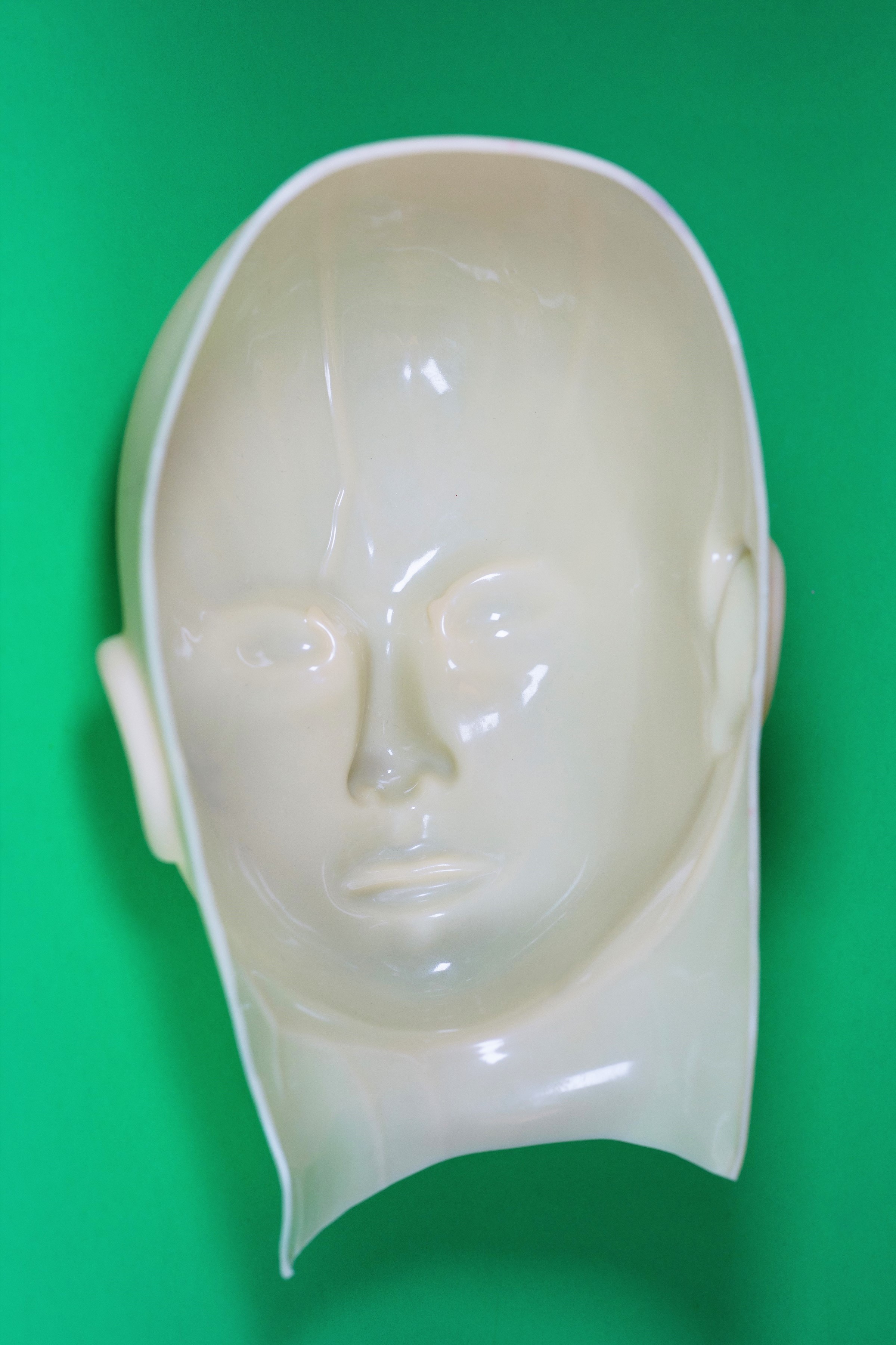

C. had been having difficulty with his balance for a few weeks. After the fall, an MRI revealed the cause: hydrocephaly, or fluid that had been accumulating and creating an intense pressure in his brain. At some point, years ago, during our marriage, he had fallen, possibly from a ladder (neither of us could really remember any kind of significant fall), unknowingly damaged his head, and the fluid had been slowly building until his brain could no longer take it. This is not a precise medical explanation, but it’s the one I’m going with.

For many years before this incident took place, I had been fascinated by a famous head case—that of twenty-five-year-old railroad supervisor Phineas Gage. In 1848, Gage was packing blasting powder into a rock when it accidentally triggered an explosion that drove a metal rod straight through his head. Gage survived this accident, which destroyed a portion of his frontal lobe, but afterward he was apparently “no longer Gage.” This once amiable man became angry and abusive; his personality had been permanently altered. Or so every basic psychology and neuroscience text would have you believe. The case of Phineas Gage is usually held up as the first time doctors were able to correlate the frontal lobe with personality, but many of these early studies are now considered questionable. There is evidence that Gage was still Gage, that he eventually recovered after the accident. Yet like many stories of this kind, the more interesting myth has persisted. I (and many others) very likely preferred it.

•••

Once I learned about C.’s diagnosis, I thought back to our marriage, to a time when, though I couldn’t really pinpoint it then, his personality had begun to change. He’d always had a bad temper. But at some point it got worse, so that when he was angry, the anger was more vicious, cruel. He was no longer C. I did notice it, but it was a slow, steady buildup, just like the fluid in his brain, and there was so much else going on, things that would have likely ended our marriage anyway. But I never suspected that his personality was being damaged from his own brain.

There is a metaphor C. often used throughout our marriage that has only seemed relevant to me now. It’s this: before football players wore helmets, they were more careful about not crashing into people’s heads. Once helmets became mandatory, the players attacked harder and got, paradoxically, more injured. C. would point to this in instances where “fixing” something actually made the problem worse. This story always resonated with me as, I suppose, various stories about head injuries did. For some reason.

•••

After the MRI, C.’s balance and other functions slowly got worse, until about a month later when doctors inserted a shunt into his brain to drain the fluid, and he was basically back to normal. Except not exactly normal. Normal the way he was before the injury so many years ago. He told me that he’d had no idea how much rage he’d been carrying around with him all the time until it was suddenly . . . gone. He was also able to read books again, to focus on things, to stop feeling irritated at everyone. The intense pressure in his brain had subsided.

After our separation, but before the accident, C. had other medical issues to deal with, but this did not keep him from doing dangerous work around his house and rescuing a large number of parrots, which he’d wanted to do for years. The parrots were always squawking and were allowed to take up as much space as they liked and, if you were not careful, would fly directly at your head as you entered the house. So much of C.’s life was about not protecting his head and I do mean this in every way possible.

•••

But this is not C.’s story; it’s mine, and the myth persisted. It was easy to tell myself that a brain injury was at the root of all of his terrible behavior and poor decisions. The question as to why I simply accepted all of this is one I refused to answer. Who doesn’t like an excuse?

One time, in my early twenties, I showed up at a therapy appointment five minutes late. My therapist at the time, who I didn’t like all that much, made a big deal about my being late, about how it wasted both our time, etc., and I just apologized and hoped we would move on. But then she looked at her appointment book and realized I’d only been five minutes late. She thought my appointment had been thirty minutes earlier and that I was thirty-five minutes late. Okay, fine, I thought, but she wanted to know why I hadn’t pointed that out, why I’d let her go on and on like that when I’d really only been five minutes late. I must have seemed crazy to you, she said. Why didn’t you say something? And this is probably all I got out of my short time with her as a therapist: why didn’t I indeed.

•••

Probably the more apt metaphor for this entire situation, better than Phineas Gage, better than football helmets, is that of the frog who jumps out of a boiling pot of water versus the frog who sits in a cool pot of water and does not notice that the water is getting hotter until it is too late. Except that this too is an imperfect metaphor. A frog will very likely jump out of a slowly boiling pot of water once the water gets too hot. But this is one of those metaphors that is useful anyway because, even though it’s not really factual, we know exactly what it means when we use it. Psychology professors like to repeat the story of Phineas Gage because they like what it suggests, even if the facts are wrong. I’m pretty sure the facts about football helmets are absolutely true though. That was the thing about C. Sometimes, his metaphors were right on.

•••

One of the things that scientists really did take away from the case of Phineas Gage is that the brain and mind are one thing, and that alone is pretty impressive. What I can finally take away from the case of my own ex-husband is that the damage to his brain/mind made things much worse for all of us, but that the outcome (me leaving our marriage) would have, should have, been the same. Though I am the kind of person who tends to obsess over random moments in the past that unintentionally changed my life, I haven’t done so with this one. It turns out I am done worrying about his head. I am looking after mine.

•••

REYNA EISENSTARK is a writer and editor living in upstate New York. You can read more of her writing here. Or all her Full Grown People essays here.

Follow

Follow

I was drawn right into this, the conversational tone, the detail about the parrots. And then the question from the therapist later, just hanging there, unanswered. Really nice.

I can relate to so much in this essay, especially “Why didn’t I indeed”–the story of my life, the story of my memoir. Thank you for sharing your story, Reyna.

Wonderful piece, thank you.