By Jessica Handler

Last semester, one of my students asked me to change his grade on a quiz. The way I’d phrased a particular question wasn’t clear, he said, which is why he earned a 95 instead of a 100. I explained to him that the quiz was one of four, which together totaled twenty percent of the semester’s overall course grade. In other words, a five-point difference on a single quiz was meaningless.

He was having none of it. He was clearly worried about his permanent record. No matter what I might have told him, I know that he wouldn’t accept that the grade on this quiz, or any quiz, has no bearing on who he is as a person. That no school administrator is going to come roaring into the room with his grades from middle school. That for the rest of his life, no one is going to judge him on his GPA.

But who teaches him, or me, about how to judge ourselves as people? Parents, to start with. Teachers, perceived as proxy parents, even if we don’t want to be. I’m thinking here of my seventh-grade teacher, Miss Moye, who left us to our own devices while she stepped out for what I realize now was a smoke break. For however long she was gone—and it couldn’t have been terribly long—the noise level in the room rose to a solid wall of released energy. I was the kid who hunkered down to read ahead in my textbook, wishing I were as audacious as the over-excitable boy who managed to climb out of the classroom via the transom over the door. When Miss (I have no idea of her actual honorific—in Atlanta in 1971, all adult women were addressed as Miss) Moye was on her way back to the classroom, the PA speaker over our heads would click on. From the principal’s office, she’d whisper, “teacher’s comin’.” No matter what we’d been doing, judgement came from above the coat closet. Act right even when you’re on your own, because someone’s watching you.

Now that I’m a teacher, I love her for this. She must have cracked herself up.

I wonder when I stopped believing in the power of the Permanent Record that loomed over school like a wagging finger. Earn a bad grade and see my “permanent record” forever scarred. Get caught passing notes or miss my turn feeding the classroom hamster, and be told by someone (A teacher? A principal? A game of telephone on the playground?) that these temporary oversights will haunt me throughout adulthood and possibly into the afterlife. The permanent record that no one ever actually saw? It would follow me to the grave.

My elementary school grades, on their flimsy pink paper, have vanished into the ether. My high school adhered to the trend in “alternative education” by disdaining traditional letter grades. Instead, our teachers, with whom we were all on a first-name, Frisbee-tossing basis, wrote paragraphs-long assessments of our personal growth and individual strengths. I have no idea what happened to these dispatches from the barefoot and bell-bottom jeans front, but I appreciate the attempt to broaden the interpretation of how a person becomes whole. My college transcripts were useful only as items in my graduate school applications. My graduate school studies resulted in my first book, which was written as a kind of permanent record of a place, a time, and a family in crisis.

What is my permanent record, if it’s not decades-old grades and well-meaning teacher commentary? On every elementary school report card, I was given a checkmark beside the “uses time wisely” criteria, verifying that I had done just that: used my time wisely. That checkmark made me proud. What I’m trying to figure out, though, is what it means to use time wisely as an adult, if it’s not reading ahead while the teacher’s out on a smoke break. Who teaches us a viable template for a “wise” use of time? When do we learn to do that for ourselves?

•••

When my father was dying, he asked me to forgive him. As I sat by the crank-up hospital bed in his living room, my impulse was to list every act of his for which I could not forgive him. “What about this?” I wanted to say. “Or that?”

Instead, I lied. I said that I forgave him. Nothing good would have come of telling him otherwise.

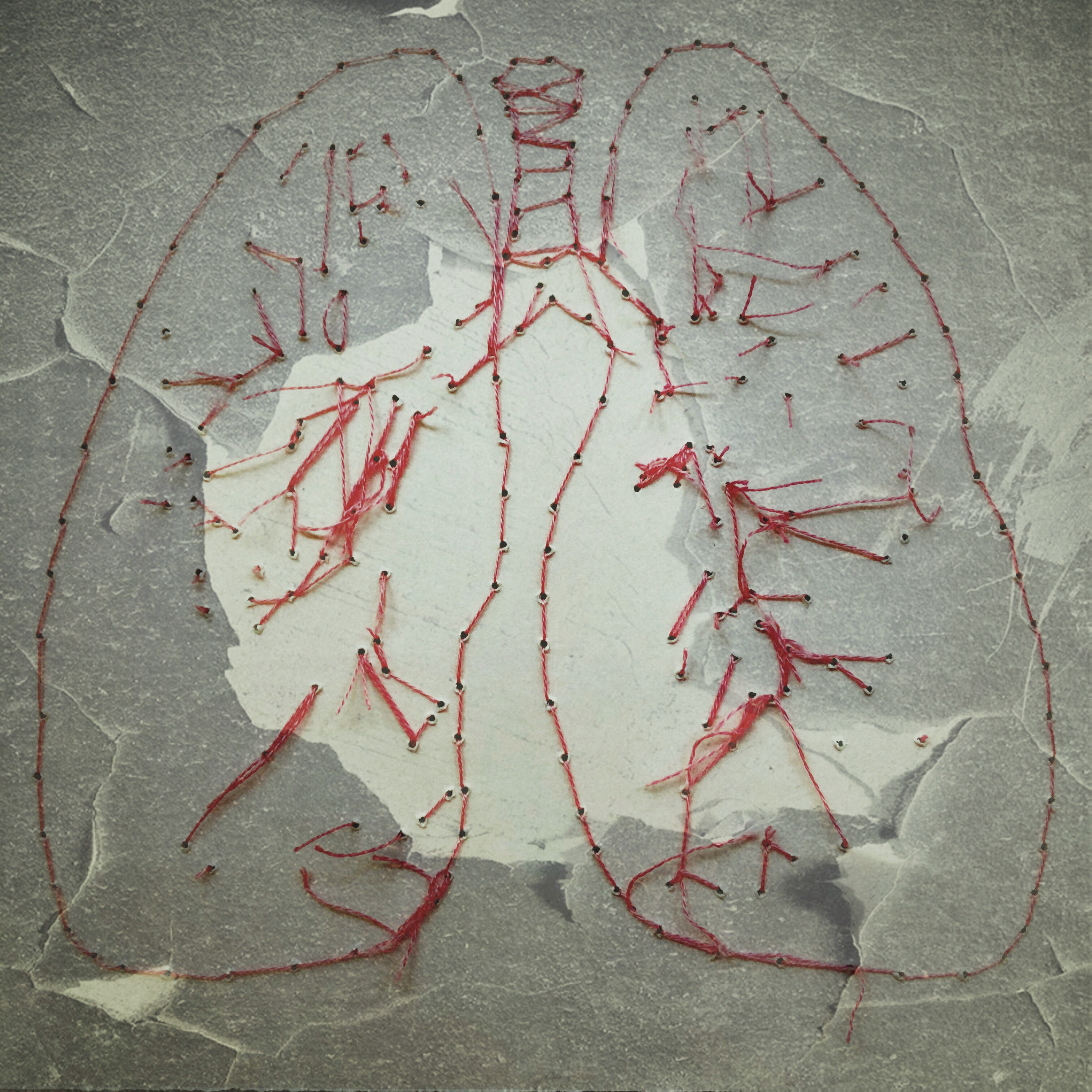

My father had turned sixty-seven that month. After a lifetime of four-pack-a-day smoking and decades of drug abuse, he had been diagnosed with cancer a year or so earlier. At that moment, he had less than a week to live.

When I was a child, my father intoned over the Passover Seder plate, “They tried to kill us, we won, let’s eat.” All the adults at the table laughed, and I did, too, believing this was the actual prayer. Of course it was, spoken by the irreverent, fun, charismatic version of my dad, acting like the kid who climbed out of the transom while the teacher was out of the room.

But this not why my father asked my blessing.

A few months ago, I awoke unsettled, because I felt that my father was in my bedroom. I could smell him. Pall Mall cigarettes and anxious flatulence. He had been dead nineteen years, but he was somehow present.

“Why are you here?” I asked the air near my husband’s nightstand.

“Forgive me?” my father asked. He was wheedling, like a child.

I closed my eyes. “No,” I said. “Go away. Maybe later, but I’m not ready yet.”

Proud of having told even a ghostly version of my father to leave me alone, I went back to sleep.

•••

My real permanent record is written, in part, in my father’s hand. That same hand that held an electric carving knife to my throat at a family dinner. I was about ten years old, and my laughing made sounds that grated on my father, especially when he was very, very high.

I wondered for years if I’d created a false memory from a roast, a carving knife, and my father’s instability. When I reconnected with a childhood friend last year, I got proof that it had happened. My friend described my mother frozen in fear at the table, unable to pull my father away from me. I remember my father’s face so close to mine that I could see his pores, his pupils spinning like pinwheels. I remember thinking, “Oh, he’s on acid.” I remember believing that was a reasonable excuse.

This is the same man who brought me, at eight years old, to Dr. Martin Luther King’s funeral. As we made our way through the solemn, slow moving crowd outside, and then inside Ebenezer Baptist Church, my father, gentle and grieving, lifted me to eye-level with the adults and turned me toward the first open casket I had ever seen. He wanted me to see Dr. King’s face up close, not on television as I had so often. What he wanted was for me to absorb the need for justice in the world.

Within a year, my father tried to shove me out of a moving car. When I tell this story, I laugh and say, “It was only in second gear,” but the irrationality of his act, his absence of judgement—or the presence of his cruel judgement of me—is what strikes my listener. My attempt to make this into a funny anecdote doesn’t land well.

I am trying, here, to reconcile a permanent record that can’t be graded. My father tucked me in at night when I was small and sat at my side reading poetry in the same elegant baritone he surely used defending his clients in court. The ballad meter of Countee Cullen’s “Incident,” telling of a child stunned and hurt by racial violence, and the mystical images of T.S. Eliot’s “Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” lulled me to sleep.

The last time I saw my sister Susie alive, my father was cradling her in his arms as he rushed her out of our shared bedroom to the hospital. She had been ill with leukemia for a year, and died a few days later. Through my lashes, I watched him run with her. He was terrified, my mother was terrified, Susie was terrified, and so was I.

After my father died, my husband and I helped his second wife sort his possessions. My husband found my father’s Twelve Step workbook. He will not let me see it. “He blames you,” my husband says, “because you’re too much like him.” Throughout the workbook’s pages, my husband says, my father blames other people in his life, but he never accepted his own role in his permanent record.

It’s become clear to me since my father died that he lived with a mental illness that may never have been diagnosed. Within its rapid cycles, he treated himself with amphetamines and Scotch. That the amphetamines were (sometimes) legally obtained and that the Scotch was eighteen-year-old single malt is immaterial. His emotional and psychological turmoil escalated as my two sisters died of illnesses, as he brutalized my mother for failings only he imagined, as whatever had transpired in his own childhood ensnared his mind. Abuse is real, no matter the ZIP code, no matter if the clothing hurled to the floor is a Brooks Brothers’ suit or coveralls.

My aunt, my father’s sister, told me the other day that her mother once refused to let a woman wearing green nail polish into her house. I can’t corroborate this, but I believe it. My father’s mother, was, as the phrase of the time went, uptight.

What I’m saying is that my father must have been harshly judged, and then judging himself harshly, turned that blade to me. I am the first daughter, the oldest, the one in whom he saw himself.

•••

A few years after my father died, my husband and I vacationed in Memphis. We visited Graceland and Stax Records, and we toured the National Civil Rights Museum. It was there, in a display of photographs by documentary photographer Benedict Fernandez, that I came face to face with an image of an unsmiling young man in a suit and tie, sitting on a curb beside another similarly attired and equally serious young man. The Black man held a placard reading “Union Justice Now!” The White man held one reading “Honor King: End Racism.”

The White man was my father.

I knew the placard. It’s framed in my house. My father had given it to me the night he came home from the vigil in Memphis in 1968. I had never seen the photograph before, never known of its existence, and there in the museum, I screamed. A group of middle-schoolers, touring the exhibit, stopped and gaped at me.

“That’s my father,” I said, pointing at the image on the wall. I began to cry.

One of the students approached me. She peered at the photograph, then at me, then at the photograph again.

“You do favor him,” she said.

•••

My father visited me again the other morning. He seems to surface when I am emerging from sleep. Maybe it’s his presence that wakes me. I think this time he wanted me to forgive myself as well as him, to stop hearing the echoes of his angry words in my own head. To stop allowing him to judge me, even now.

I don’t know if I can forgive him, entirely. I can’t grade an abusive father’s relationship to a daughter. If he gets an A for some things and an F for others, does that really average to a C? On the days when my own fist splits my lip to silence his taunting voice in my mind, I’d say no. On the days when I turn to a poem and physically, truly, feel his longing for words, I’d say yes. If I wrote an assessment, as my high school teachers did for me, would I implore him to get the help he needed, or would I suggest something benign like learning to meditate or taking up a musical instrument?

Perhaps I should be grading myself, since I’m the one living with this permanent record.

I am trying to understand how to create a permanent record for him and for me. For us together. I want to teach myself to judge him fairly. I don’t know if I can forgive him, as he asked, or if doing so is a requirement for his, or my, final grade. But in trying to learn this, to read ahead in the book that he’s put down, I want to believe that I am using time wisely.

•••

JESSICA HANDLER is the author of the novel The Magnetic Girl, winner of the 2020 Southern Book Prize and a nominee for the Townsend Prize for Fiction. The novel is one of the 2019 “Books All Georgians Should Read,” an Indie Next pick, Wall Street Journal Spring 2019 pick, Bitter Southerner Summer 2019 pick, and a Southern Independent Bookseller’s Alliance “Okra Pick.” Her memoir Invisible Sisters was also named one of the “Books All Georgians Should Read,” and her craft guide Braving the Fire: A Guide to Writing About Grief and Loss was praised by Vanity Fair magazine. Her writing has appeared on NPR, in Tin House, Drunken Boat, The Bitter Southerner, Electric Literature, Brevity, Creative Nonfiction, Newsweek, The Washington Post, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Full Grown People, and elsewhere. She teaches creative writing at Oglethorpe University in Atlanta, and lectures internationally on writing. www.jessicahandler.com.

Follow

Follow