By Kathleen McKitty Harris

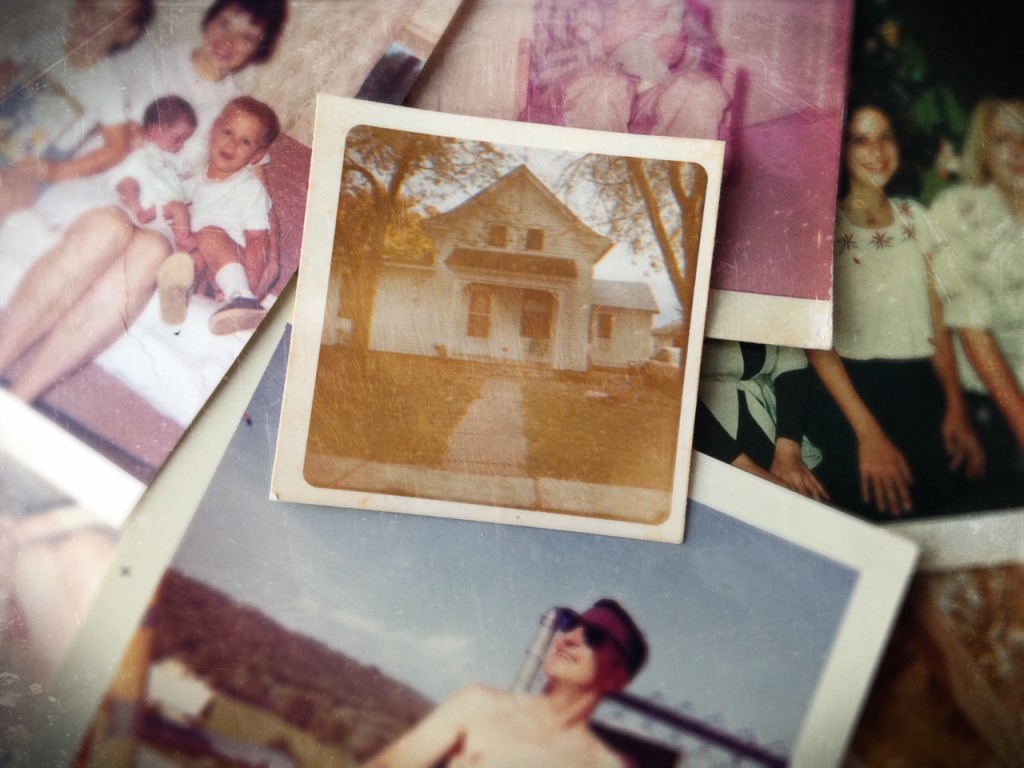

My father doesn’t want the pictures anymore. When he finds them in drawers or old shoeboxes, he passes them on to me—in used mailing envelopes bearing his new address, or in secondhand shopping bags printed with the names of retail stores long defunct, with curlicued fonts that spell names like “Bambergers” or “Gimbels.” When he does so, I am struck by the incongruence of my childhood memories, grouped together in no particular order.

The pictures usually make me cry when I take a moment to look at them later by myself. They guide me back to living rooms in houses long since packed up and sold, to the feel of scratchy rompers and dresses sewn by my mother from McCall’s patterns, and to the smell of my grandmother’s Chanel No. 5 perfume, cloying and comforting on hot July days in Brooklyn backyards. They return me, quite viscerally, to the freedom of childhood summers, to the comfort of love and acceptance craved by an only child and bestowed by a dysfunctional—albeit well-meaning—extended family, to days when what has become would never have been foreseeable or possible.

My parents divorced ten years ago, after more than thirty-five years of marriage. They were high school sweethearts, who amassed decades of memories between them. These pictures are markers of what once was and what never should have been, of what cannot be fixed, and what will never return. So they’re put aside, someplace dark, and tucked away.

I was thirty-five, in my own marriage for nearly ten years, as I witnessed the dissolution of my parents’ union. The small, lacquered coffee table, the Pfaltzgraff dishes, the Christmas ornaments, the kitchen chairs with cane seats—all once merely functional items—were now essential to my mother and father, after passing through their lives largely unnoticed. They were life rafts, and my parents clung to them, alone and adrift, as they became unmoored from the weight of their married life. It was jarring to visit each of them in their makeshift apartments and see the physical objects of our former home, now unmatched and without their counterparts. Tables without chairs. Couches without pillows. Cherished collections, now halved.

The photographs, however, were largely left by the wayside. Who wants the wedding album from the marriage that didn’t survive? Who needs the box of Kodachrome slides from the honeymoon in late-sixties-era Kauai, that Christmas in the first apartment in Manhattan, the first ride in the new car, or the time we went on that trip north to Vermont and stopped along the way for fruit pies to take home? Who wants to remember that there was good there, even if it was only as bright and brief as the flash of light capturing it? Who wants visual proof of the dour, cold faces, the spark gone from someone’s eyes, the distant body language, the signs, all the signs—long before the other had awakened to it?

Most of our family photographs remain in a storage unit that my mother has rented for too long in Connecticut, because she still can’t bring herself to sort through everything. When her promised dates of delivery come and go unfulfilled, I don’t press her for them, out of kindness. My father has a few in his possession, and he offers them to me when he thinks of it. When he does, I discover moments I’d forgotten, or that I had never been cognizant of, given my age in the photos.

There are familiar memories, new to me again from alternate angles of relatives’ cameras. I sift through shots of birthday cakes and party hats, cellophane-wrapped Easter baskets, tricycles with streamers, toys long since lost or sold at garage sales, presents stacked under tinseled Christmas trees, and every-day moments on outerborough summer streets and in backyard pools. There are blurry ones, many poorly framed, with ripped edges and creases. They were captured with cameras that we no longer own — my parents’ old Instamatic with the blinding flash bulb box, from my uncle’s old Nikon, or from the Polaroid we kept for a while around the house.

Sometimes, they humble me as I realize how little we had—and how much there still was to go around. We all lived in close quarters, seemingly on top of each other, in two-family houses and apartments and row houses. We were together. Often. This explains why several relatives often usually weren’t speaking to each other, my desire to have borne my husband more children, and why I yearn for a houseful of people yelling and clattering together on any given holiday.

One photograph will never be returned to me. It’s a vertical shot of me in cap and gown, bearing a broad, white smile, at my college commencement. I’ve taken my glasses off, for vanity’s sake, which ironically worsened my look with the tight squint of near-sighted eyes. I can sense that my father is there somewhere before me, squeezing the shutter button, but I’m not exactly sure of anything except his shadowy shape.

I was the first woman in my family to graduate with a bachelor’s degree from college, and the first person to go away to college at all. My parents were proud of my accomplishments, and of their numerous sacrifices to get me there. After my graduation, my mother had a large print of the photograph framed to suit the decor of my father’s office. It matched the cherry credenza behind his desk, and he displayed it there for several years in his midtown Manhattan office.

When my father’s company moved downtown to the World Trade Center in the mid-nineties, he brought the picture to adorn his new office on the 92nd floor. On September 11, the day the towers fell, he survived because he was simply late to work that morning, and had not yet arrived at his desk.

In the weeks that followed, I thought of the photograph’s journey and wondered what its fate had been. Had it fluttered out to the murky Hudson River? Had it incinerated in the collapse? Would it be recovered in someone’s backyard in Brooklyn, clinging to a chain-link fence and wrongly labeled as the photo of a 9/11 victim? The thought process was my irrational way of distancing from the physical horrors that had occurred. The thought would surface when I could only focus on the chaotic flight path of flimsy photo paper, unable to humanize the abject pain and fear that took place on that day.

Photographs are small truths. They house our past. They help us to remember who we once were, when we have strayed so far from our beginnings.

•••

KATHLEEN MCKITTY HARRIS is a writer and native New Yorker, living in northern New Jersey with her husband and two children. Some of her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Creative Nonfiction, The Rumpus, Literary Mama, Brain, Child, and McSweeney’s. She has also been named as a Glimmer Train Press short story finalist and as a three-time finalist at the Woodstock Writers’ Festival Story Slam. Her website is sweetjesilu.com.

Follow

Follow