By Pennie Bisbee Walters

I tried to talk my sons out of getting tattoos. To me, tattoos seemed like something for circus performers or punk rockers: a way to mar lovely, pristine skin. They were ugly, in design or placement, sometimes both, like the one of a snake I’d seen creeping up the cheek of a man’s face at the beach. I’d been noticing more and more tattoos during our summer beach vacations. Military sayings like Semper Fi stretching across a young man’s shoulders, the black words stark against his sunburnt skin. An intricate lacy sleeve of bright flowers and ivy covering a barista’s arm from wrist to shoulder. The odd trail of pink stars on the calf of the mother holding her toddler’s hand.

Snakes. Someone else’s words. Flowers and ivy. Colored stars. They were all unnecessary and permanent, I told Tim and Sam. What design could you get that you’d never regret? Don’t forget. You have a tattoo forever. But kids are all about the here and now. Tim, who was sixteen at the time, talked about getting a tattoo of Pittsburgh’s skyline or the small black-and-tan outline of our family dog. Sam, who is nearly four years younger, wanted a tattoo of the Coca-Cola polar bear, but with a bottle of Mountain Dew instead of the cola, claiming to be a rebel. I didn’t know if they were serious or just trying to provoke me, but I hoped the urge would pass before they turned eighteen and could get one without my assent.

•••

The idea first came to me while skimming through a small tabloid newspaper while I waited at a restaurant. Maybe it was the colorful ads for punk band concerts and head shops or the small brown tattoo of an owl on the back of the hostess’s calf that my daughter Meg pointed out. Something made me turn to her and say, “I’d like to get a tattoo someday. One of Tim’s birthdate or name or something.”

Meg snickered, then said something like, “Oh you’d never do that.” But my sister Kim said, “Yeah, that would be a nice thing to do. To remember him.”

•••

After getting a haircut one bright afternoon in August, I walked the four blocks to a Starbucks for a mocha, a drink that, in my grief, had become a staple—something about the warmth of it in my hands and its decadence. Allowing myself that indulgence was, in a weird way, a self-kindness that was still hard for me. I had to remind myself I was worthy of it. Like I reminded myself kids with good parents were dying every day. From cancer or car accidents maybe, though not drugs. Maybe I had been a good parent. But despite the number of drug overdoses—in Pittsburgh and everywhere else it seemed—it was still something I didn’t believe.

Kayla was standing beside the tattoo parlor three blocks down from my hairdresser, her head shaven except for a small blue tuft above her forehead. One side of her skull boasted her newest tat: a black tarantula beside the pink open bloom of a flower. Weeks before, I’d seen her photo on Facebook and thought, as a mother would, Oh Kayla, what are you doing to your body? That tattoo was just the latest in a series that spread across her chest and legs and arms. What led her to get one after the other after the other? Wouldn’t she someday regret at least one of them?

“Hey,” she said.

“Hi, how are you?” I walked up and hugged her. I remembered the card she sent to me after. I remembered all of them.

“I’m good. You okay?”

“Yeah, I’m doing okay.” I noticed the blue lipstick around the filter of the lit cigarette dangling in her hand. Blue lipstick looked so natural on her. The tattoos probably helped with that. “Hey, I’m thinking of getting a tattoo. Of my son’s handwriting. Can they do that?”

“Oh, that is so cool. What a great idea.” She dropped her cigarette to the cement and ground it out with the toe of her shoe. “Come talk to Ed about it.”

Ed was tall and in his forties, with a long gray ponytail and tattooed arms. His stencil machine could make an exact tattoo of Tim’s handwriting for just fifty dollars—what seemed a pittance. Before the parlor door even closed behind me, I knew that I would do it. It would go on the inside of my right wrist because he was right-handed. I could peek at it whenever I wanted to. It would be my secret.

•••

I made myself go into his bedroom, hoping to find his handwriting on a school paper in his desk drawer or a page of his Narcotics Anonymous workbook, if I could bring myself to read through it again. I’d read it the day after he was found, but remembering anything from those first days was like pulling something out of the ocean’s center, bottomless and dark. Some memories were just gone. I was thankful for that.

As soon as I stepped onto the dark blue shag carpet, I took a deep breath. This room still held things from his good years, before he got sick, before things went so far they could never be the same. Baseball trophies, bobbleheads from Pirates games with his brother and dad. The faceless brown bear I’d named Bruno before Tim could talk. The thin white poster board covered in pictures of him. Of us all together. After the viewing, I’d propped it up against the mirror of his dresser, unable to pull the pictures off.

And now I wanted the tattoo there on the inside of my wrist. To look down and see it throughout the day and night. We had lost so much of him. He left his belongings on buses or at friends’ places where he’d stayed briefly those days he had nowhere else to go. And items I suspected he’d sold for drug money—his Xbox 360, my favorite Laurel Burch earrings, Meg’s nano iPod. Other things had probably been stolen by roommates when he lived at three-quarter-way houses after rehab, things we’d bought him before realizing just how much shit we were in, things that were cheap but desirable to someone who had little: the e-cigarette we bought him to keep him from the real, more dangerous kind, the black rainproof jacket with the warm fur lining, the silky soft throw because he loved the feel of soft things against his skin. All those things had gone missing, along with the son I’d known.

•••

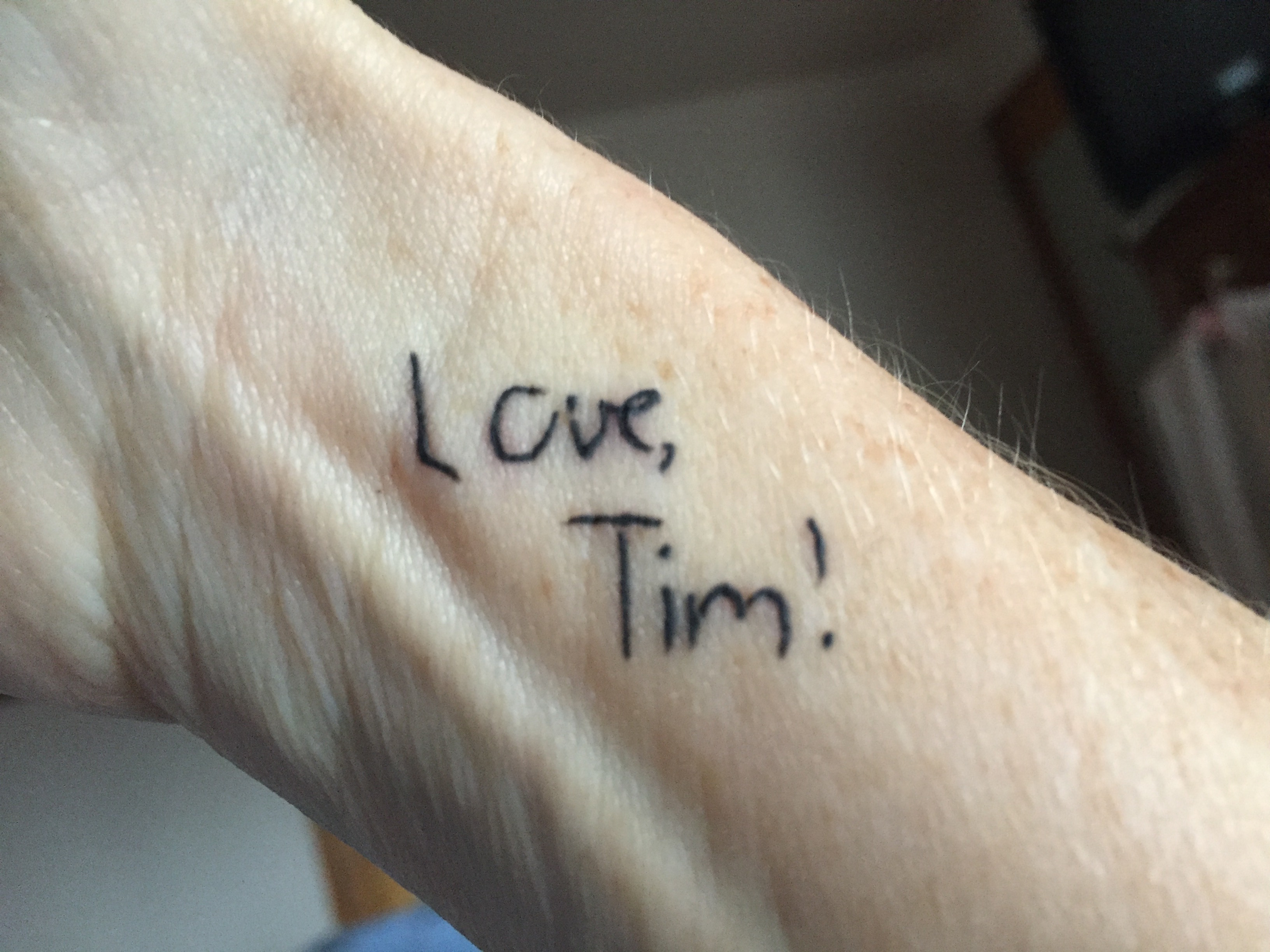

When I couldn’t find anything with his handwriting in his room, I remembered the Mother’s Day card he wrote to me when he was seventeen and still living at home. It was a bright shade of yellow, an oddly cheerful color for him to choose then; he always seemed to be somber, even sullen. The front of the card read “from your son. Mom, because of you, I grew up a healthy, well-mannered person who always tries to make the right decision,” and the inside read “As far as You know anyway.” Those words mocked me, since I knew he was already smoking marijuana then. Arguments about it had replaced civil conversations between us, despite the therapists and doctors, despite my pleading. Below the typed words “Happy Mother’s Day!” were the handwritten words, “From Tim!” that he’d scratched out and replaced with “Love, Tim!” when my husband Ken pointed out “From” was unnecessary. Tim sometimes needed to be reminded of what was obvious, lost as he was in the outer-space regions of his teenage mind.

•••

My tattoo would be monochromatic and simple: the words Love, Tim! in black ink. What my son wrote to me. His printing. His words. I imagined seeing them whenever I turned over a soapy dish in my hands or spread lotion that smelled like oranges and ginger across the dry palms of my hands. I’d linger in those tasks, seeing the black, block handwriting that wasn’t yet there. I could feel him write the words, his hand twisted around the pen, face tight with concentration. He had hated his handwriting homework, even before the torture of writing cursive letters began, but now those shapes he hated drafting seemed to be all I had left.

•••

On my fifty-fourth birthday, I felt like a switch had flipped inside me. I had to get the tattoo that night. The urgency I felt was a wave pushing me along. I didn’t resist.

“Hey there. What can I do for you?” Ed said. He was the only one working at Jester’s Court Tattoo that night.

“Hi. I was here before. I’m Kayla’s friend. I wanted to have a tattoo made from this card.” I opened it and pointed to Tim’s words.

“Oh yeah, I remember. Just words, right? We can do that. It’ll be fifty dollars.”

We stood together looking at the card, and I explained how I wanted to include the exclamation point but not the thin underlining that Tim had drawn under his name. Meg and I had debated in the car whether to include those extra markings. At first, I thought I’d just include his name, but then decided that Love was an equally important word, since I knew in my heart that it was true. Despite how things had ended.

One of our last phone conversations had convinced me of that love, relieved me of a little bit of my guilt. That talk had been an absolution, a gift, though I didn’t see it at the time. Love, however powerful, was not, it turned out, strong enough to cure or rescue or tame. But love lived on in spite of death, of heartbreak, of a parent falling short. I had learned that much.

Meg liked the punctuation mark because it showed the exuberance and energy he had then. I liked the idea of a marker that showed who he once was, before the addiction took full hold. Thinking of him adding the exclamation point made me smile, although it made me feel sad, too. Every memory had those two opposing sides: happiness and sorrow. Glad to have known him, so sad that he was gone. I lived a dichotomous life now.

“Take a seat here and get comfy. I’ll be back in a flash,” Ed said, walking to the stencil machine. When he returned and handed the card back to me almost gingerly, like he knew its value, I slipped it carefully back into the plastic sleeve I’d brought it in and laid it beside me on the chair. He rubbed my wrist down with alcohol and then a milky lotion to help the stencil ink stick to my skin. He showed me the stencil first, then peeled the back of it off and held it parallel to my wrist, ink side down.

“I want it tilted so I can read it.”

He shifted the paper, waited for my okay, and then pressed it onto my skin for several seconds, rubbing it once with his thumb. When he peeled the stencil back, Tim’s words were left behind.

The needle, when he took it out of sealed plastic wrapping, was longer than I’d imagined and reminded me of the IV needle the nurse had pushed into my skin the night I went into labor with Tim nearly two weeks early. I’d felt so unprepared to parent him.

I watched Ed feed the needle into the top of the small machine and turn a stubby knob until the needle was in place. Holding the gun in his hand like a pencil, he dipped the needle into a cup of black ink the size of a thimble. I heard a thick buzzing noise as he tested the machine, operating it through a small pedal on the floor near his feet. He bent over my wrist and I heard the buzzing again as he began at the top of the letter L. I watched as the needle punctured the skin on my wrist, leaving ink on top of the purple stencil markings. When I asked Kayla what getting a tattoo felt like the day I stopped into the parlor, she said like a cat scratching your sunburn. For me, it was just a subtle scraping, dull and somehow distant, like it was imagined or in the past. Maybe I wanted to feel Tim so badly that I welcomed the feeling of his words being etched into my skin, my body that had held him for those eight and a half months, kept him safe. Maybe the tattoo really didn’t hurt much. Maybe it did, but I was too numb to feel it. Or maybe I wanted to feel pain to feel him again, I don’t know. I only know the needle felt light and quick.

When we left the tattoo parlor, my wrist wrapped with bright purple tape, I was euphoric, a feeling little known to me since Tim’s death. I felt lit and warm and accompanied in a way I hadn’t when I walked in. My skin was now home to a secret kinship, a shelter for a part of my tender, vanished son, suddenly found.

•••

When I’d seen him last, his hair had grown shaggy and wild again like when he first started using. He mostly wore black cotton t-shirts that hung on him like a tent and bore the silhouettes of Notorious B.I.G. or Big Pun. I’d grown used to those XL shirts that swallowed up his five-foot-eleven frame, his narrow hips and shoulders, as if he wanted to hide, his pants so long and wide-legged they billowed up around his bright green and white skate shoes. His clothes were more than a fashion statement: He didn’t want anything pressing in on him.

•••

For weeks, I babied the skin of my right wrist, following Ed’s instructions carefully: wash three times a day with an antibacterial soap, pat it dry with a paper towel, then rub in a fragrance-free lotion and let the tattoo get some air. I enjoyed the ritual of it, the patting dry with a gentle touch, the feel of the lotion, cool and soft.

•••

When I first considered the tattoo, imagined the script carved into my wrist, I kept going back to my penultimate conversation with Tim. I said before it was a gift, though I spent much of the call pleading with him to listen, to hear me, when—I see it now—he was no longer capable of it. The addiction had suppressed his ability to listen, the way that other diseases suppress your immune system, leave you unable to fight. Maybe if I tell you what he said, you’ll understand. Even without having been in my shoes those six years. Maybe it will be enough to recount his words that day.

I had been at my office with a stack of pages to edit, but I was getting little done. Most days were like that for me then. A struggle to focus, to care about work when my son’s life—and therefore mine—was becoming a natural disaster. He’d been texting me for forty-five minutes, seeking my approval, my acknowledgement that his plan for the immediate future held merit.

Here’s what he was planning to do just weeks after his second overdose and week-long hospitalization: move into an apartment with Jake, a young man about his age whom he met at rehab. Two addicts who thought the occasional use of marijuana or can of beer would be no problem. Two addicts still living in denial, unable or unwilling to face the reality of their disease.

When the phone rang, I considered not answering. I had so much work to do, and debates with him took a circular path, his reasoning so illogical there was no possible resolution. Afterward, I had trouble retracing the tangled branches of his thought. It was, I suppose, a symptom of his drug use, his brain struggling to follow its own thoughts, the connections numbed or diverted. But I knew I had to try.

“Hi, Tim,” I said, doing my best to not sound annoyed and probably doing a poor job of it. I was lousy at hiding how I felt, especially with him, especially when I felt afraid or angry—two emotions he always seemed to bring out in me.

“Hey, Mom.” His voice always sounded monotonic, flat and emotionless, his mind forever planted firmly somewhere in the middle of happy and sad. I wondered if he ever felt anything anymore without drugs.

“Tim, I think you need to go back to rehab now. It’s what you need. Not moving in with Jake.” When he didn’t respond, I kept going. “You almost died. Again. Tim, you need help.”

“Mom, it’s okay. I’m done with that shit. Jake and me are gonna get an apartment and it’s gonna be fine. I got my job now, and he’s working. We can afford it.”

“Jake is an addict, Tim. He’s a nice guy and a friend, I know, but he’s not good for you. Remember what they said at rehab? That you need to change your friends, your habits, your hangouts. It’s the only way. You need to find friends who are clean and have been that way for a while.”

“It’s fine, mom. He does a little marijuana now and then, but that’s okay. We can do that. A lil marijuana or a beer ain’t gonna hurt. I’m off the hard stuff, I promise.”

I swung my chair away from my desk until it faced the window. Hearing him talk that way was scaring me. Most of my knowledge of addiction came from the Sunday family sessions at rehab, and I remembered what the counselor said every week: Addicts had to leave their old friends behind. Old friends led to old habits and old habits led to relapse.

“Mom, did you hear me?”

“Yeah. You know you can’t drink at all anymore, Tim. Or use any drugs.”

“Mom, it’s okay. I can do it once in a while.”

“No, you can’t. Mel was clear on that. You can’t. You have to stop it all. And you have to get new friends.”

“Mom, I can’t. And I don’t want to. I have a job now, and I want to be out on my own. I can do this.”

I stood up and looked at the sky, at the single bird gliding toward the building just a hundred feet away. Tonight, when I was locking my door and heading out, the whole flock, black and busy, would be gathering on its rooftop. “Tim, you can’t. It’ll happen again and this time—” My voice fell into my throat and I started to choke up, my voice suddenly thin and wispy. “Tim, you can’t. You won’t survive it again. You…you will die. And I can’t take that, I can’t.” I started to cry. “I can’t let that happen, Tim. I love you. You have to do what you can to stay clean.”

“Mom, I love you too, but it’s my choice. I can’t go back to rehab. I just can’t do it again. I’m gonna move in with Jake, after I get a few more paychecks.” He paused, and I watched the lone bird land on the rooftop, his black silhouette clear against the darkening sky.

“And Mom, no matter what happens…if I die, it’ll be my fault, not yours.” The quiet between us thinned and stretched out, but I was too terrified to speak. I could hear the ticking of my office clock, the blood rushing in my ears. I began to sob openly, holding a wet Kleenex to my face.

“Mom, I know you and Dad love me. You guys are the only reason I’m still alive.”

•••

Looking back, I knew. The way he was talking, there was only one way things could turn out. He wouldn’t go back to rehab. He wouldn’t stay clean. He would make what few choices he could, decide the few benign things that drugs had left him control of, like it or not, without my help.

Today I wonder, was he saying goodbye to me? Did he know it, too? To leave me with those words I’d cling to just weeks later, words full of his love for me and Ken, proof that he knew all we had done to try and save him.

I don’t know the answer. But the word Love—the way he wrote it—on my wrist above and just to the left of his name—is how I remember that call, his words, uttered to me with all the certainty his numbed heart could feel, a mark of his love for me, true.

•••

PENNIE BISBEE WALTERS, who works as a technical writer in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, is currently working on a memoir about loving and losing a child who suffers from the disease of addiction. Her poems have appeared in Voices from the Attic.

Follow

Follow