By S. Craig Renfroe, Jr.

The nurse looked at my chart. “I see you’re allergic to Basilhefflinne?” Basilhefflinne is a made-up word because to this day I don’t know what she actually said.

“No,” I said. “I have no idea what that word is.”

She wrote something on my chart. I was afraid she wrote, “He doesn’t know what that is.”

“Should I?” I asked. “Know what that is?”

She didn’t say.

“How would I know if I was allergic to that?”

She wrote something else on my chart.

I quit talking.

She prepared me for the surgery. It was a simple procedure, they had said—outpatient, performed in the doctor’s office. I had something on my lip, embolus, cyst, something, and they were going to remove it. Simple.

So simple I hadn’t cancelled my afternoon classes. I was teaching composition at a small private liberal arts college. In the South. In North Carolina. In a large city. In Charlotte. It’s Queens. Queens University. Queens University of Charlotte. Though technically at the time it was Queens College. Without the “of Charlotte,” which they added when they upped it to university, afraid students would think they were in New York, I guess.

The doctor came in. I had been referred by my GP, which was mainly what he did, that and told me to bike to work. This doctor was also a cosmetic surgeon—he told me this so that I wouldn’t be concerned about the effects of the operation on my face, any fears about disfigurement. I was instantly afraid of disfigurement.

Simple.

“We’re going to use another anesthesia,” he said, “because I see from your chart that you’re allergic to Basilhefflinne.”

“I’m not. I have never heard of that. At least I don’t know if I am.”

He wrote something on my chart. And then he stuck me with a needle in the mouth, the lips, and the face. The nurse put on Motown. I was instructed to lie down. There was a little towel that he put on my face at the nose and above—“to keep the light out of your eyes.” There was a contraption that went in my mouth. My face was numb. The doctor tugged on my lip. It was only when something warm ran down my chin onto my neck that I realized it was blood and he had been cutting me.

I’m not sure how long it lasted, but I was in and out in around an hour, so not long. Right at the end, he gazed at his handiwork and said, “Perfect. No one will know once it’s healed. Beautiful job.” And he was right, no one does know now, but saying that out loud was still kind of arrogant, right? “You’ll need this for when the anesthesia wears off.” It was a prescription for hydrocodone. “You’re not allergic, are you?”

“No.” Was I?

•••

Dorothy Parker, Algonquin Round Table wit, left Martin Luther King, Jr. her estate without ever having met him. After King was assassinated, the estate went, again according to her wishes, to the NAACP. In that same will, it said she was to be cremated but failed to spell out what was to happen to those ashes. Lillian Hellman, her friend and executor, not wanting to pay fees to the funeral home for storage, had them moved to the estate lawyer’s office. Dorothy Parker’s ashes remained there in a filing cabinet for seventeen years. Today, they are interred next to the NAACP’s headquarters.

•••

While filling my prescription, I marveled at my face in the pharmacy bathroom mirror. It was horrible. I was disfigured. My lip was black and swollen, and the stitches made me a kissing Frankenstein. I was not going to teach my classes later that day—this decision I made strictly out of vanity before realizing taking the hydrocodone meant I wouldn’t be doing much of anything.

I called the College of Arts and Sciences admin. She was one of the kindest people in the world, but she also refused to learn Excel, and so she did classroom assignments by hand using some arcane hand-drawn charts on taped together legal paper, which meant we spent the first two weeks of the semester moving classrooms. She also had a habit of God blessing her/him/it, which meant that person or thing was not living up to expectations. I told her I had outpatient surgery, and it took more out of me than expected (God bless me), and could she put notes on my classroom doors saying class was cancelled. She was happy to and told me to get better.

Then I made one more stop at the library. I had recently discovered you could check out movies for free from the public library, and so I freaked out several story-time-going young children with my face as I looked for a video I hadn’t seen. I was on a personal mission to see every single one of the “Greatest Films of All Time” (as defined by anyone who happened to make such a list) and figured I could use the drugs to help me get through some of the tough movies that I had been putting off. So I took the copy of Singing in the Rain and the hydrocodone back to my apartment.

•••

Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of that high school student bedeviler The Scarlet Letter—that is, used-to-be bedeviler; as I understand it now, they mostly read business emails. Hawthorne died in his sleep in the White Mountains, the same day his son was initiated into a fraternity by being put blindfolded into a coffin. Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of the pallbearers, wrote of Hawthorne, “I thought there was a tragic element in the event, that might be more fully rendered,—in the painful solitude of the man, which, I suppose, could no longer be endured, and he died of it.” For a man who wrote an essay called “Friendship,” Emerson was a real jackass of a friend. Though I guess the two weren’t actual friends, but neighbors. There are lots of journal entries of Emerson dissing Hawthorne’s writing and reports of Hawthorne hiding when Emerson would be headed down the path to his house. Emerson was buried in a white robe.

•••

My frenemy came to visit me at my apartment that afternoon. We’d met when I started as an adjunct at the university where he was a lecturer. The University of North Carolina at Charlotte is huge, at least to my reckoning, with over twenty thousand undergraduates. It is a monster of education, a bloated blob of learning. The English department had to staff all the English 101 and 102s for all the first years, though their class numbers were actually ENG 1101 & 1102s—that’s how big they were. I started as an adjunct but was offered a lectureship there and Queens at the same time. Ultimately, I chose Queens, and it has made all the difference. But for a while I taught at both—six to eight classes in total.

Before I left, I had gotten to know my frenemy around the office. We’d see each other at the coffee shop or at the bookstore or at the arts district. And then, somehow, we just hung out.

He was the worst kind of handsome man, the kind that hadn’t realized it until recently. Free of a long-term relationship, he was terrorizing women like a condo-bound lab unleashed in a dog park. Before this breakup, we used to watch Blind Date in his apartment, a reality show where snarky potshots were taken at couples on blind dates. Now I was watching Singing in the Rain on hydrocodone alone.

“It doesn’t look so bad,” he said. He said it with part disappointment and part aggravation, as if I’d misled him about my disfigurement.

“You didn’t have to come over.”

“I wanted to bring you some bread. It’s banana.”

The only kind of bread I hate is banana bread.

“And it was on my way to the shelter.” He taught creative writing to the homeless. He used orange juice on his cereal like milk because he was vegan. He was unbearable.

“Thanks for coming,” I said.

“I know you’d do the same for me.”

•••

Sherwood Anderson died from accidentally swallowing a toothpick. I could never get into Winesburg, Ohio. Tennessee Williams supposedly choked to death on the lid of an eye drop bottle but actually died instead from a drug and alcohol overdose. Writers seem prone to that one. Poe, for example, allegedly died a drunk—but it turned out that was an invention of a prohibitionist, using Poe’s celebrity as a warning. We can only guess at the real cause, and speculation has included anything from rabies to cooping, the practice of voter fraud where victims are drugged or forced to drink and then made to vote over and over—these repeat voters sometimes dying in the process.

•••

My other friend wanted to come over as well—I had the capacity for about two friends at the time, this being before Facebook, which has increased my capacity to around seven hundred. She wanted to bring me things, like soup, and she was very insistent on a vitamin E rub. For the scarring.

I didn’t want her help because I had been raised on twenty-one acres in the rural underbelly of North Carolina by people who believed in doing it all themselves. I had interpreted this self-reliance to mean: if you don’t do anything for me, I don’t have to do anything for you. I’m pretty sure that’s also what Emerson meant. I shared my theory with my frenemy, who was a big Emerson fan, but he only sighed. Then I told him Emerson was buried in a white robe and was a real jackass to Hawthorne.

So I didn’t want my friend bringing me soup and vitamin E because then I would have to bring her stuff when she was sick. I already owed my frenemy a visit and some kind of bread he didn’t like.

•••

Mark Twain died twice. The first time was a mistake. Foreshadowing our own media outlets that rush to report without any verification, a newspaper printed Twain’s obit when it was his cousin, also a Clemens, in London who had died. Twain responded to a member of the paper asking about the mix up: “The report of my death was an exaggeration.” Only later, polishing his rejoinder for retelling, did it take it on its more famous form: “Reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated.”

•••

The email came later that night. I read it, I think, between getting up from the recliner, the TV blank from the autostopped VCR, and going to bed, leaving the TV on. Or maybe I read it in the morning after turning said TV off. Either way, I didn’t respond.

The subject line read: The rumors of your death…

The message said: Are greatly exaggerated. People thought you had died. The dean had to get involved, but we straightened it all out. Hope you’re well.

It was from the director of composition—my immediate boss. When I returned to Queens, I would suffer through the Mark Twain quote innumerable times. But it was apt, because the rumors of my death had been significantly exaggerated.

Here’s what happened as far as I could piece together: the admin put up my cancelled class signs. Groups of students eager to learn gathered by the signs in disappointment. Among this group, one student—and I know who, or I assume I do, to be a terrible person, one of those students who makes you wonder why you’re bothering to teach at all, other than to barely survive—this person said something to the effect of: “Class is cancelled because he’s dead.”

I tried to put a positive spin on this: “He’s such a dedicated teacher that he’d only cancel class if he were dead.” Though, I suspected it was more in the spirit of: “I hope they cancelled class because he’s dead.”

Another student, someone with less guile and not attuned to sarcasm, overheard this line and believed I had died. In her next class, she was visibly upset, God bless her. I imagine her with fat tears rolling silently down her cheeks. At the time, my death would have been a “That’s so tragic,” as opposed to now which would be more “That’s too bad”—I’m hoping to get to a “We all have to go sometime.”

The professor of the grieving student asked what was the matter.

“My English teacher died.”

“Who’s your English teacher?”

“Renfroe.”

“Renfroe died?”

Queens is still a small place, but then it was tiny. A thousand students, maybe. Class size at ten to fifteen. Everyone knew everyone. If UNCC was an impersonal educating machine, Queens was a learning family, with all the good and bad that implied. I was shocked when I first realized that Queens students knew one another outside of class. Back at the behemoth, I had to spend time getting them to know one another, but here I was having to deal with their social lives infecting the class, all the fights and romances and gossip. Lord, the gossip. It spread like gossip.

So that first professor, concerned about my wellbeing and/or eager to gossip, asked other faculty who in turn asked people in the English department, until someone finally asked the admin. She, God bless her, must have taken medical confidentiality very seriously and thought for some reason I wouldn’t want anyone to know about my outpatient procedure. So when asked if I were dead, she said, “I can’t talk about that right now.” Which, of course, meant, yeah, he’s dead.

The dean was finally consulted before the admin would tell them I had called in sick. It was an embarrassing way to draw attention to my flub, especially considering I hadn’t been working there very long. Here I was called out in front of the entire college for not planning ahead or possibly playing hooky.

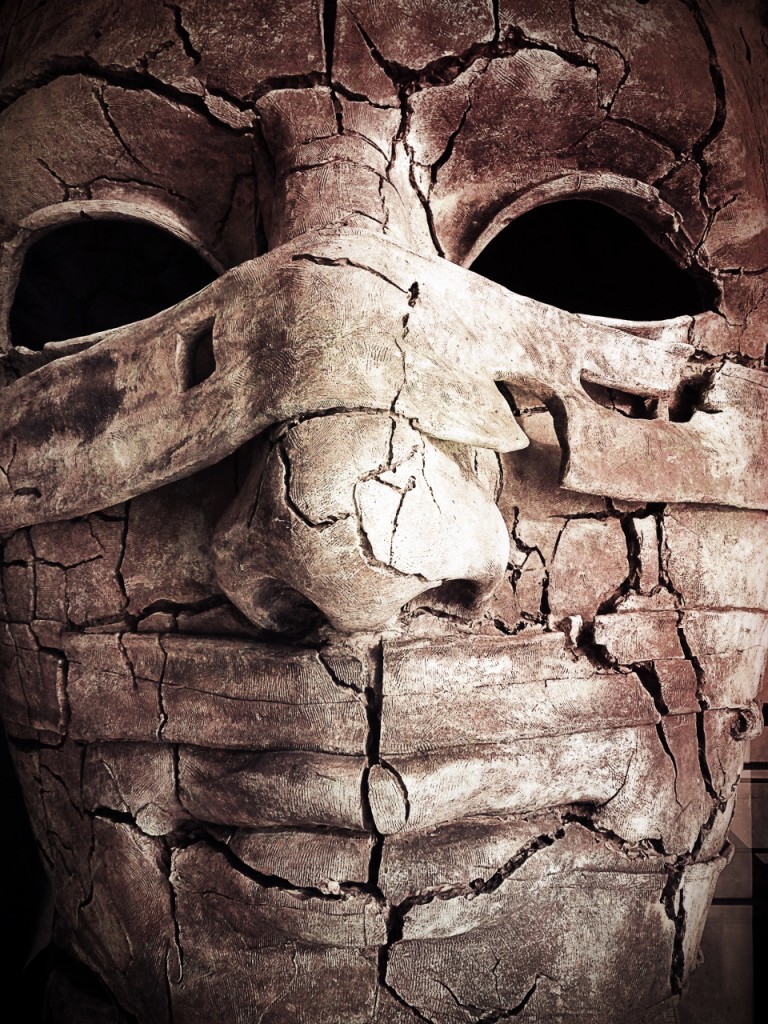

The dean didn’t hold it against me though—he was formerly a philosophy professor and I had impressed him by talking about Jeremy Bentham’s headless mummified body, which is actually just his skeleton in clothes padded with hay. Bentham, one of the founders of utilitarianism (“The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.”—the Spock doctrine) and also an atheist, willed his body for dissection on the condition the remains be preserved in an “Auto-Icon,” still housed by the University of London. His mummified head was deemed too grotesque a topper and so the Auto-Icon has a wax sculpture head, the real one sitting covered between his feet. For a time, I was obsessed with the death of writers and philosophers.

The dean had pictures.

•••

Shakespeare is supposed to have died on his birthday. Twain, when he died the second time for real, fulfilled a kind of prophecy because beforehand he had said, “I came in with Halley’s Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don’t go out with Halley’s Comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: ‘Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.’” A couple days after Halley’s Comet’s closest pass to Earth, he died of a heart attack.

•••

I told my frenemy the whole story about my death misunderstanding as we graded comp papers in the strip-mall Starbucks.

After taking it all in, he said, “Why do some women want to talk dirty in bed? Isn’t regular sex good enough?”

“I don’t know. Pretty crazy though, right? Over a minor operation.”

“It’s barely noticeable,” he said. “I wouldn’t even notice it.”

“Right,” I said. “That’s why the story. Strange, right?”

“I wouldn’t even bring it up.”

I don’t anymore. And I also don’t see my frenemy anymore—we’re not even Facebook frenemies.

My other friend brought me the vitamin E despite my protests, and I used it and the scar went away. And I let her call me late at night, three or four in the morning, whenever she had insomnia and we talked. She was worried about death and knew I was too. I’m not sure she was specifically worried, as I was, about the story aspect, every life having to end like every story. There are lots of ways to stop, some intriguing, some forlorn, some bizarre, but some just end.

•••

S. CRAIG RENFROE JR. is an associate professor at Queens University of Charlotte. His work has appeared in Puerto del Sol, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Barrelhouse, and elsewhere. You can follow him @SCraigRenfroeJr.

Follow

Follow