By Jessica Handler

The auctioneer’s receipt for my mother’s tableware reads, 78 pieces Rogers ‘First Love.’ $150.00. I put the receipt in a green plastic file marked “estate.” The hundred and fifty dollars I put in a household checking account.

Copious, easily tarnished silverware with extravagant names was a standard wedding gift in the fifties, when marriages were copious.

Salad forks, dinner forks, olive and pickle forks. Knives for checking for food between your teeth by eyeing the slim mirror of the blades. Soup spoons, dessert spoons, serrated grapefruit spoons, nestled large protecting small and smaller.

Marriages are easily tarnished.

I doubt that my father was my mother’s first love, despite the brightly named wedding silver. When she was fourteen, she held an unfulfilled crush on her cousin. His name was Paul, and he was sixteen. He could play the hell out of the piano: he rolled through some boogie-woogie. She never mastered boogie-woogie, but she played the hell out of Chopin.

At twenty-three, my father appeared to be a good catch.

I have a blurry memory of going fishing with my father, of gray predawn light, of mist, of trying to bait a hook.

My father was no outdoorsman: how could it be possible that we went fishing? Squinting at the narrow mirror of my mind’s blade, I can’t find an answer.

I have a memory of failing to catch anything.

A few years ago, a student told me he knew the guy who’d whistled the Andy Griffith theme for the TV show soundtrack. You know it: someone whistles a hearty tune while Opie and Andy amble to the fishing hole.

They appear to love each other.

I borrowed the idea in another classroom. I explained to my students how, when writing a screenplay based on a novel, a writer needs to show what’s inside a character. How to show closeness? Opie and Andy, walkin’ to the fishin’ hole.

It’s kind of a dumb example of depicting physical representation of the unspoken.

Try showing this in a screenplay: my husband laughing at a video on his computer of a mud-soaked hippo letting loose a blast of farts. My husband is in tears from laughter.

He’s a very funny guy.

I shine from the inside when I can make him laugh. I see him bent large in the blade, and I see myself small, barely a fleck. Turn the blade and I loom, large eyed and small mouthed, and he tightens to a speck.

That’s easy to show, but not this. Sometimes we don’t have anything to say to one another.

A colleague once told my husband to warn her if he planned to employ humor in conversation.

We think that’s very, very funny.

We didn’t register for silver when we married. We got beautiful dessert plates from Tiffany’s and a hideous, sharp-cornered crystal bowl that I wish now I’d had the sense to return. I lost it, buried it in the basement or a closet.

You could put your eye out with that thing—it’s worse than with a knife.

We came to the marriage with our own flatware from brand-name discount stores. The forks and knives, the soup spoons and those other spoons for what—yogurt? cereal?—cohabitated nicely.

Someone bought that fancy silver as a wedding gift for my mother and father. My father’s parents, most likely. They had money. My mother’s parents might have scrimped and saved for it. They loved her more than silver.

I polished that silver after Thanksgiving dinners, after the Seders over which my father intoned, “They tried to kill us, we won, let’s eat.” I appreciated the diligence required to wash, dry, polish, wrap, settle. Salad forks, dinner forks, olive and pickle forks. Knives and soup spoons and dessert spoons and serrated grapefruit spoons. A silver claw with four retractable prongs for sugar cubes. An archly modern Georg Jensen cheese knife, adopted by this silverware family.

You had to wash the silver in warm water, dry it, then dull each piece with a menacing-smelling cream from a plastic jar, polish it with a soft gray cloth, then put it to bed like dressed-up kittens in perfectly shaped red velvet forms inside a walnut case.

And I sold it all, earning less than the cost of a week’s groceries. One hundred and fifty dollars is padding, polish, a sliver of safety money.

I baited the hook: the silver had become small fish in the estate world.

The auctioneer took the heavy walnut box (heavier than I remembered) along with a quality but faux Mission desk, a cedar-lined blanket chest (I kept the linens), boxes of various “smalls.”

My own first love wasn’t a cousin, but a good looking boy in my high school whose parents had emigrated to Georgia from South America. He taught me to say “love” in Spanish. Yo te quiero.

This means I want you.

We had sex for the first time in my bedroom. My parents were at work. My sister was somewhere in the house, watching television, or practicing the piano.

Andy Griffith, maybe, or a Satie Gymnopedie. No boogie-woogie yet.

I was twelve, and my boyfriend was thirteen. I had made a bet with my best friend—which of us will lose her virginity before the other? I caught the first boy. I won.

I lay there and thought of groceries, of what was in the refrigerator and the pantry. I’d need to start dinner before my mother came home from work. I would make coq a vin. Or meat loaf. There were also fish sticks. I didn’t realize, at twelve, that these could be seen as sex jokes.

Sometimes when I set that table, I used the good silver.

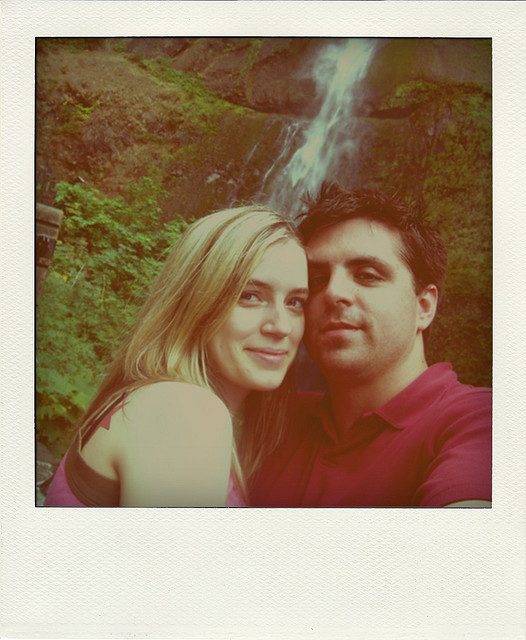

Now, my husband and I polish each other until we shine. We nestle together, large protecting small protecting large. We look in the distorted images we make in silver blades, and we laugh.

•••

JESSICA HANDLER is the author of Braving the Fire: A Guide to Writing About Grief (St. Martins Press, December 2013.) Her first book, Invisible Sisters: A Memoir (Public Affairs, 2009) is one of the “Twenty Five Books All Georgians Should Read.” Her nonfiction has appeared on NPR, in Tin House, Drunken Boat, Brevity, Newsweek, The Washington Post, and More Magazine. Honors include residencies at the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, a 2010 Emerging Writer Fellowship from The Writers Center, the 2009 Peter Taylor Nonfiction Fellowship, and special mention for a 2008 Pushcart Prize.

Follow

Follow