By C. Gregory Thompson

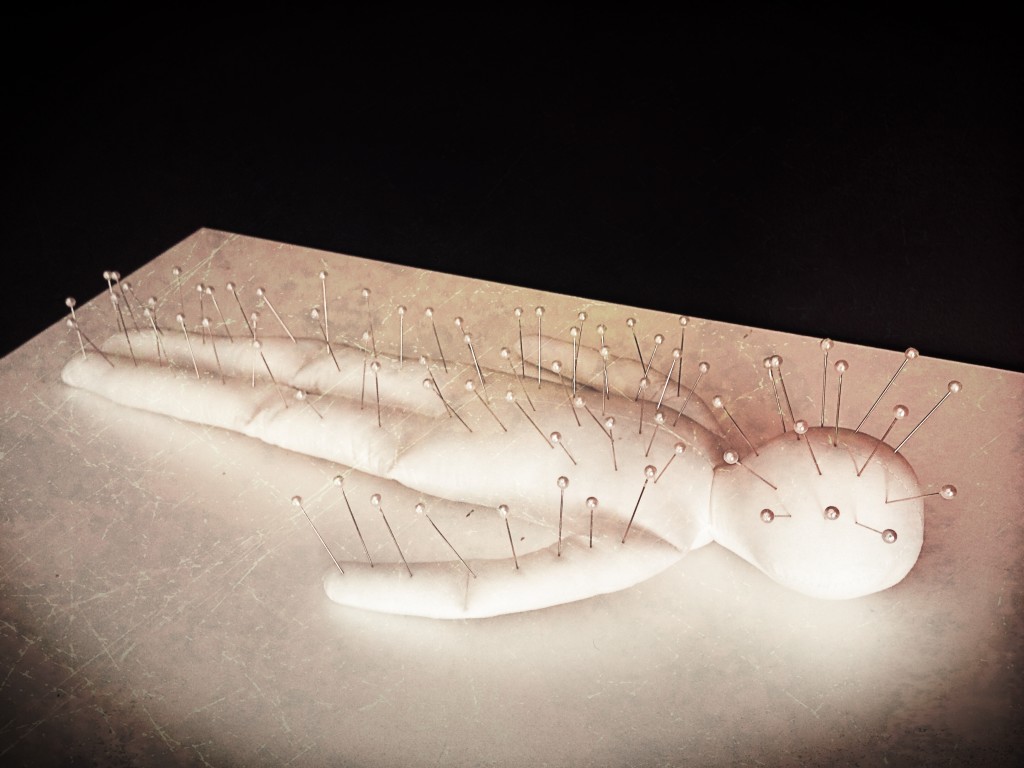

I see my dead father. Not in dreams, but physically, alive, out in the world. He’s always alone. I’ve seen him numerous times. He seems at peace, not lonely or struggling to understand his fate, his new whereabouts. Not laboring to return to the earthly plane. Problems endured alive, resolved; no longer important. On his own, no one else to answer to, to provide for, or support. Children, ex-wife, and wife number two no longer a responsibility or concern. Mistakes made, unmet expectations abandoned and not rectified. Unfulfilled and incomplete duties not complete and not fulfilled. Pain and sorrow, remorse and apology, lifted. A freedom he didn’t know in life. An aura of wonder surrounding him. He died on April 23, 2009, at age seventy-four, his cremains now interred at a cemetery in South San Francisco.

I saw him while on a Caribbean cruise in 2015. The ship docked at St. George’s, Grenada, and we had a half-day to explore the island. Walking back from Grand Anse Beach I noticed a man sitting on a pylon looking out to sea—my father, Ed. At least, it looked exactly like him. The bend of his back, the slope of his shoulders, the side-view of his face, his gray hair, even the clothes—K-Mart Bermuda shorts, a well-worn tee-shirt, brown leather fisherman sandals; his favored outfit. My father, Edward Willis Thompson. I did a double-take. I stopped and stared, studying, wondering, wanting, and needing. I wanted to go to him, but I did not. I wondered if it could actually be him, knowing—in my rational mind—it was not. In my fantastical mind, wishing it to be truth. I needed the healing that didn’t happen when he breathed.

He sat alone; no one else on the beach or near him. The way he gazed out at the water—as if he was there, on that pylon, permanently. Like he’d found his place to rest, to live out his eternity. Possibly, I was meant to pass him, to discover him there, at his final resting place. So I’d know he was okay, now at peace. The sereneness of my vision of him led me to believe this was the case—a communication from his beyond to my within. And it could have been him. Who’s to say it wasn’t? We don’t actually know where the dead go. Maybe “Heaven” is a favored place from life. The beach—any beach, especially a tropical one—Dad’s favorite place in the world.

Before the Caribbean sighting, I’d seen him a handful of times: in a Home Depot parking lot; in a crowd at the mall; on the street in Glendale, California, where we live. Each time I had the same experience, I thought: Jesus, that man looks exactly like my father. After the third sighting, I didn’t question whether it was or was not. For me, it was. Even if it’s as straightforward as me seeing my father’s corporeal doppelgangers, it was still him. This is not something ghostly. It is something else. Ghosts are fine, I like them, I have no problem with them, but these sightings are not phantasms. And it’s okay. I’m not sure I need to understand or label them. They simply are. I find them soothing and calming. Is he reaching out to me? Possibly.

•••

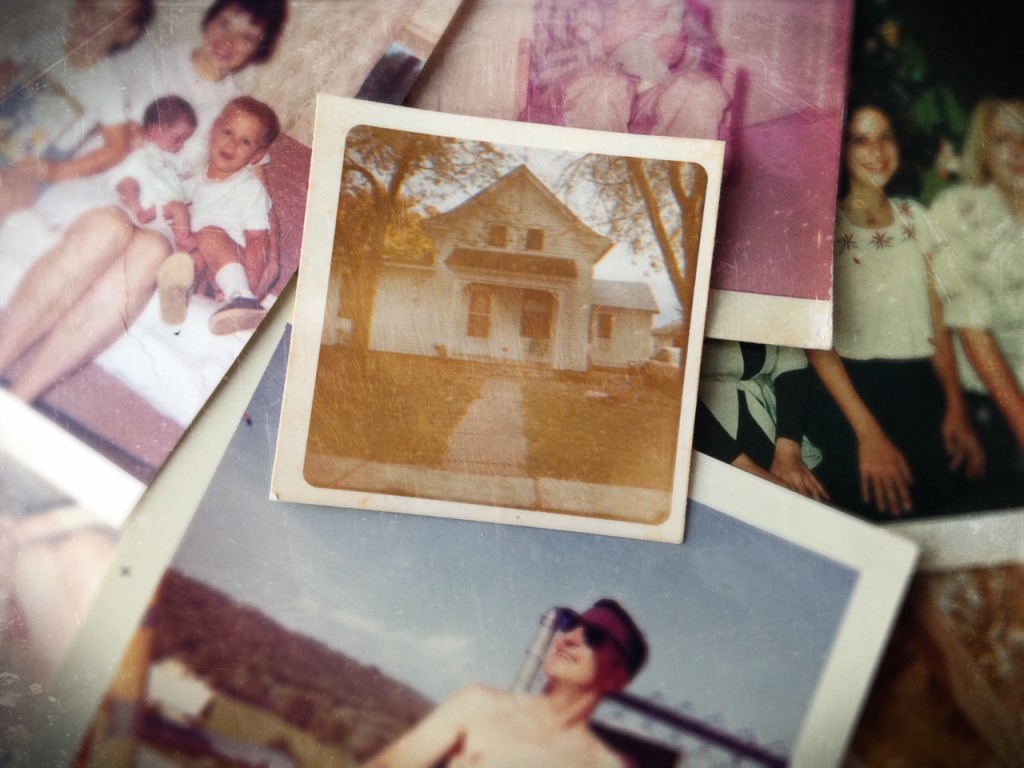

I was never all that close to my father. My parents divorced when I was five. He left the family and wasn’t around much when my sister and I were growing up. We’d see him on summer vacations, spending a week with him staying at a cheap motel in Avila Beach, California. The days filled with sun, sand, and water—and a whole lot of fun. He seemed to enjoy the time we spent together. He spoiled us rotten by buying us everything we wanted: ice cream at all hours; any toy we pleaded for; cash to spend ourselves. Standard absentee father conduct—making up for ever-present guilt. At the end of the week, he’d drop us off at home, our white skin now a dark brown, temporarily happy, father-sated yet sad all the same. We wanted him to park the car and come inside, return to our mother, to the family.

The vacations ceased when I was eight, the moment he married his second wife, Mabel. She wanted as little to do with us as possible. He went along with what she wanted. A strong-willed, opinionated woman married a weak-willed and lazy man. A mama’s boy, he wanted to be taken care of—the way his own mother had spoiled him. Mabel provided a clean, comfortable home, three squares a day, and her body at night. They had an unspoken understanding. He did what she wanted, and, pretty much—sadly too—only what she wanted. From that point on my interaction with him was sporadic at best.

•••

When he was sick and dying of lung cancer, I visited him in the hospital. A shell of the man I once knew, he recognized me despite his dementia; he knew I was there and was happy to see me. Dying in a hospital bed at the VA facility in Palo Alto, California, his six-foot-four frame, legs twisted yet still gangly long, slid down the hospital bed so his feet dangled uncomfortably off the edge. I only spent a couple of days visiting; there was little to do except be in his presence and pull him back up the bed so he didn’t dangle off—over and over. He’d move, or wiggle, or shift his body, and down the bed he slid. Due to dementia, his stage four lung cancer, and the medications he was on, holding a conversation with him was not possible. Expressing my anger and displeasure for the way he treated us—his two children—would not be happening. Instead, I sat close to the bed and held his hand, or helped him eat ice cream or his lunch or dinner, feeling sorry for him in so many ways. I hurt for him and for myself. I did my best to do the prescribed things a person does for another, a relative, a father, who is in the throes of dying. I told him I loved him. I wish I’d done all of it because I truly felt love for him.

And, I can’t say I felt much either when he died. Mostly, I was saddened by what we were unable to achieve: a loving father and son relationship. A seemingly ethereal idea foisted upon me by societal expectations, out of reach, a dream in our family—but something I still desperately wanted. I didn’t mourn his loss in the accepted ways one is supposed to when losing a loved one. My grief was tied to lost possibility, to what would never be, not to losing my “father,” my “Daddy.” I hadn’t spent enough time with the man for the type of familial intimacy to develop that would warrant true and deep feelings of grief over his loss. To add to my confusion and misery, his wife cremated and interred him without telling my sister or me. There was no viewing, no service, and no burial—at least none we were invited to. Even in his death, we were treated the same as when he lived—excluded like we didn’t belong or exist.

•••

A recent sighting took place at our local Trader Joe’s. Dad was putting groceries into the trunk of a car. I found myself thinking, there he is again. Like before, it looked exactly like him—the height, the build, his movements, the clothes, all Ed Thompson, my father. A rote calmness emanating from him—a task as mundane as grocery shopping joyful. Not a care in the world. Similar to the island pylon resting place, I’m left thinking he’s still in that Trader Joe’s parking lot, still loading groceries into his trunk, over and over, on a continuous, never-ending loop, stuck in time and not unhappy about it in the least. A chore no longer a chore but a happy task. A final resting place or action could be malleable, or exist in multiple places, couldn’t it? The world of the dead not curtailed by human, earthly barriers of time and space.

Observing him, I wondered if he was buying groceries for us. Like this father, the version I saw in the present day, might go back in time, and do the right thing. Was he going to bring groceries to help feed my sister and me? To add to our food stamp-supplied coffers? To remove some of the burdens on my overworked mother? To ease her financial strain? He’d bring the groceries when he came to pick us up for a weekend visit. Like a good father and ex-husband, he’d hand the bag of groceries to my mother and then help us with our suitcases. We’d drive off with him to a motel for another spoil-us-rotten weekend, momentarily forgetting how he wasn’t in our lives. Or, would this be one of the numerous occasions when he didn’t show up?

One of those times, my sister and I, dressed, coats zipped up, suitcases ready, waited patiently by the front door. Then, the allotted time passed and no Dad. Hours went by, still no Dad and no phone call. Our mother tried to locate him by making a series of calls. Her anger with him—for us, for herself—palpable. Coats removed, suitcases stashed, she wiped away our tears, and finally, a phone call came days later. He didn’t have money for gas, or his car broke down, or he had to work, or who knows what the fuck else of an excuse he’d come up with. Not once, but over and over this took place. Our childhood a never-ending, continuous loop of disappointment.

•••

How to explain simultaneous love and hate? Or concurrent joy and anger? Recently, since seeing my dead father out and about in the world, I realized how I felt about him: I loved him and hated him; he made me happy and so fucking mad. I now see my entire involvement with him existed on a yo-yo continuum. He could be the most charming man—father—in the entire world one day—bringing us gifts, taking us to the movies, showing us a good, fun, time. Through a child’s filter he loved us, he brought us happiness, and we loved him back. Followed by a long absence, a cancellation or a no-show when he was supposed to take us for the weekend, or some other equally injurious hurt. After one of these, the tears, the anger, and the hatred bubbled to the surface, polluting the prior felt love. This up and down, love to hate, joy to anger went on all through my childhood, into my adulthood, up to his death.

Buddy—the nickname he earned growing up with four siblings outside Oklahoma City—was a jokester and a kidder; a big, overgrown kid. Bighearted too, generous of spirit, he was kind to small children and animals. Without question, I know a gentle soul resided within the man. Social, he loved people, he loved his family; he had Okie and country blood in his veins. He used to sing Merle Haggard’s lyrics “I’m proud to be an Okie from Muskogee” over and over. And he meant it. From him, I learned to appreciate my Okie heritage. The salt of the earth, hardscrabble people my relatives were and still are; survivors. People and a place he evolved from.

But, there was another side to the man that didn’t jive with the Okie-identifying, softhearted big kid version. Life kicked him in the teeth over and over, and he took the hits. He didn’t fight back. His divorce from my mother. His unintended abandonment of his children. His failed career—stuck in middle management after earning an MBA. His second marriage to a horribly controlling woman. A woman who cut him off from his siblings, from his children, from his friends. The parts of him I hated were the results of him quitting, giving into life: his confusion about right and wrong when it came to us kids, his passivity, and laziness in not doing the right thing or allowing others to decide what he wanted, or even what he felt, and the selfishness all of this manifested. He ended up a depressed, inadequate, and indolent wimp, and he knew he was. And I hated him for it.

I now see the hatred overrides any love I may have felt. It is the stronger of the two emotions, and I don’t know if it is changeable. I have often wondered if it would have been easier not to have a father, to not know there was a man out there in the world, living and breathing, who was my so-called “father”—the man who gave me life. The mere fact he existed and ignored us feels more problematic, difficult, and painful than if he simply didn’t exist or had permanently disappeared. The hurting hurt over and over and over, and it still does. And, once dead, no going back. A door slammed shut, hard, in my face. I’d forever believed there would be enough time to fix it. Then, there was not.

•••

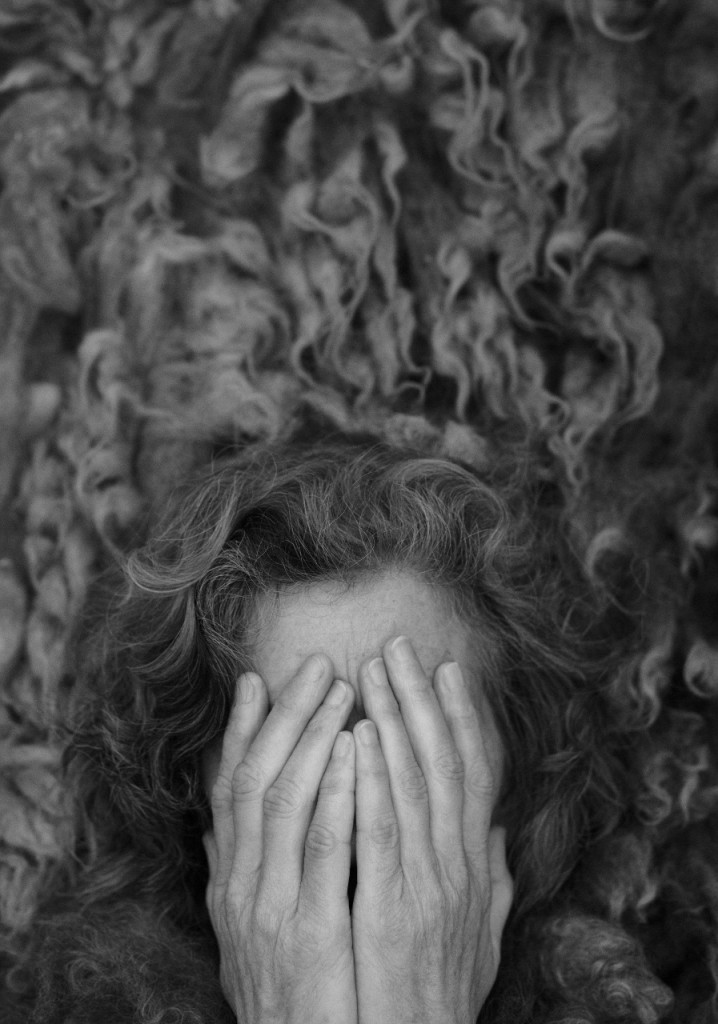

I have a French friend who, when she was a young girl, lost her mother to suicide. She once told me a story of walking along the crowded streets of midtown Manhattan where she lived during her early twenties and passing a woman who looked exactly like her long-dead mother. Her mother she hadn’t seen since childhood. She stopped and turned around to look for her, and when she did, the woman wasn’t there.

I understood why she told me the story. It gave me chills then, it still does now. Was the woman she saw her mother, a ghost, something else? Who can say? It’s not important. For her, it was real. Somehow, the woman who brushed past her and then vanished was her mother. I feel the same about my fatherly sightings. He can be real for me, there in the flesh, if I decide he is. He hasn’t ever come to me in my dreams, not that I remember or am aware of—only in these sightings. Unfinished business, it could be. I suppose we have quite a bit. I wanted something from him he could not give, and I know he was aware of failing my sister and me. I know he felt guilty and remorseful but not enough to fix it. That’s the unfinished business.

No matter the explanation or understanding of the sightings, they bring me comfort. These are unanswerable questions. I accept he might be somehow trying to reach me. Why would I ever not? Why would I cut myself off from that possibility, from any possibility? I wouldn’t and I won’t. After all, who truly knows the truth of what is out there, of how these things work? The dead versus the living. We should all be open, like a conduit, to all of it, to any possibility. Shouldn’t we?

•••

C. GREGORY THOMPSON lives in Los Angeles, California where he writes fiction, nonfiction, plays, and memoir. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Offbeat, Printers Row Journal, Reunion: The Dallas Review, Every Writer’s Resource, and 2paragraphs. He was named a finalist in the Tennessee Williams/New Orleans Literary Festival’s 2015 Fiction Contest. His short play Cherry won two playwriting awards. He earned an MFA in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts at the University of California, Riverside/Palm Desert. He is on Twitter as @cgregthompson.

Follow

Follow