By Sarah M. Wells

“What song do you want to dance to, Dad?” I asked, scrolling through lists of popular father-daughter dance songs.

Nothing seemed right. No Michael Buble or Paul Simon or Stevie Wonder would cut it; this, after all, was my father—my flannel-shirt-and-faded-blue-jeans, muddy-work-boots, calloused-hands, five-o’clock-shadow, “fetch-me-a-Miller” father. What qualified as “our song?” Maybe “Feed Jake.” Maybe “Friends in Low Places.” Maybe “Act Naturally.” Maybe “There’s a Tear in My Beer.” Hank and Garth and Buck and the Pirates of the Mississippi sang about misery, friends, beer, and mama; they didn’t sing anything about their daughters.

By the day of our wedding, Mom and Dad had settled on a song. “It’s a surprise,” they said.

Four months earlier, I had come home from college graduation with my boyfriend who they liked well enough but were still warming to, and an engagement ring. Brandon had asked my dad’s permission first, of course, out of my hearing the day before, and Dad had said yes—he hugged me extra-long before I left, cap and gown still on.

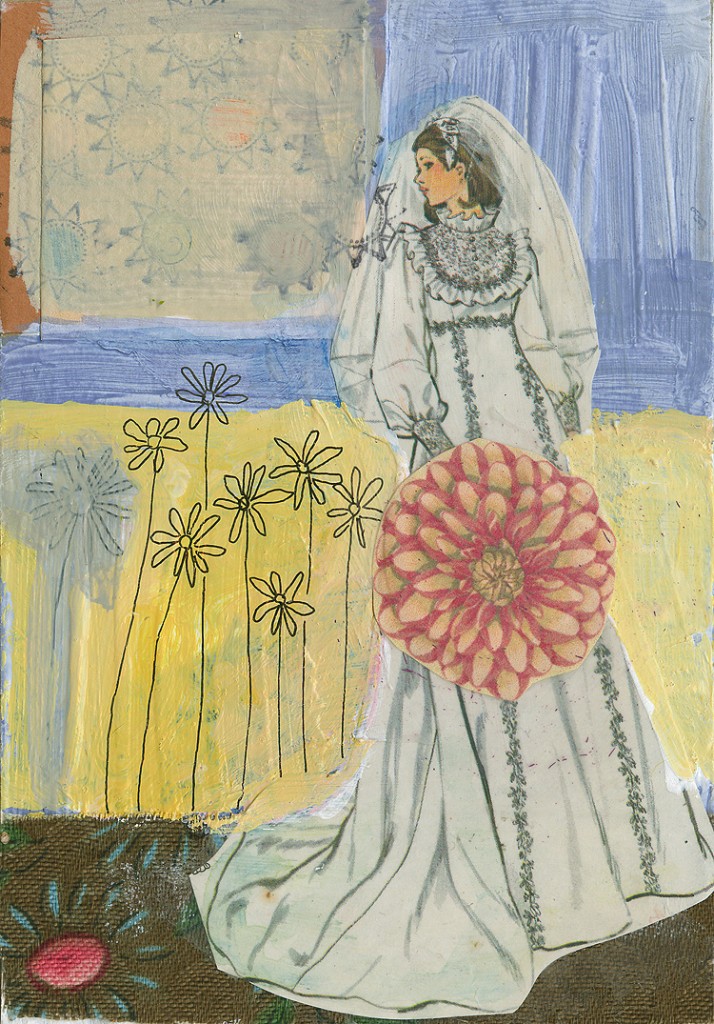

In the early planning days, Mom and Dad offered to write us a check instead: big party vs. down payment on a house. We waffled for a day or two, but in my head were visions of a white dress and a man in a tux waiting for me, dreams of dancing and spinning under a spotlight, all of our friends and family clapping and celebrating.

It was my day to plan, along with my mom, who navigated the wedding planning with me like she was my maid-of-honor. Mom and I picked the flowers—sunflowers and blue delphinium—the same that decorated the cake display we chose. We taste-tested the catering, got weepy-eyed over my bridal gown and veil, and designed the party favors together. The reception venue was our decision, too, even as my soon-to-be mother-in-law raised her eyebrows and said, “Really, a barn?”

After the father-daughter dance to whatever song Mom and Dad had picked, Rhonda and Brandon would get the party started. Rhonda’s choice for the mother-son dance was easy: Louie Armstrong would sing “What a Wonderful World” for thirty seconds, then the record would screech to a stop. Brandon and his mom would look confused for a second until Lou Bega’s “Mambo No. 5” would begin to play. It fit them perfectly.

I wrote the order of music and communion and rings; I designed the program and inscribed a poem; I recruited our friends as musicians. Brandon and I selected most of the songs and all of the Bible verses for the ceremony. We picked the pastor and the bridal party and the style of music to be played at the reception. We determined the flavor of this wedding, and this wedding would taste just like us.

The guest list: that was their decision—the parents—and it grew, and grew, and grew, until we all silently stared at it sitting on the kitchen counter. Who could we possibly cut? No one. Maybe there were a lot of other commitments that weekend, and the guest list would just… trim itself. Maybe in true Father of the Bride fashion, we could declare, “Well, cross them off, then!”

Also their decision: the alcohol. We toyed with the idea of a dry wedding for about a twelve-hour timespan because Brandon had just gotten a job at a new school, and we weren’t sure yet exactly how conservative they were. A few of his new employers made Round One of the guest list. It hadn’t been decided if they’d make the Round Two cuts.

“You want a what?!” Dad asked, his voice rising steadily. “We are not going to invite all of our friends to a wedding and not have alcohol. What kind of a party is that?”

“But, Da-ad,” I said. “We just thought, you know, the school… and maybe…” but it was no use. My excuses were weak, anyway; it wasn’t like Brandon and his family and our friends and our relatives never kicked back and drank a glass of wine or a can/ six-pack /case of beer, so why pretend otherwise and ruin a good time? Besides, it was Dad’s call. Dad’s decision. Dad’s lead.

So, okay, beer and wine, Dad. And yes, invite all of those people, even those people I won’t know when they come through the receiving line, and I’ll look at Brandon and he’ll look at me, and we’ll both smile and shake their hands and give them hugs and thank them for coming. And, okay, yes, pick our father-daughter dance.

•••

Down the aisle we went, Dad in his black tuxedo looking sharp, no John Deere hat to cover his balding head or shadow his features. His hand was tight in mine, tense against a few hundred sets of eyes that watched us while we two-stepped—left-together, right-together—our paces matched, the Fugman stride slow and easy like a mosey.

I saw only my future husband at the end of the aisle where Brandon waited for me. When we reached the pastor and he asked, “Who gives this woman to be married to this man?” Dad answered gruffly, “Her mother and I.” I turned my gaze back to him for just that second and wrapped my arms around his neck, and he held on, squeezed and squeezed, then released me to my groom, taking his seat in the sanctuary while I remained standing.

Later, after the bridal dance ended and I parted with a kiss from my new husband, our spunky blue-haired emcee called Dad onto the floor. Dad had donned his Father-of-the-Bride ball cap as soon as the wedding ended and wore it now as he met me for our dance. The bubbles from the bride and groom dance settled and popped on the dance floor. A slow piano, slide guitar, and light percussion played.

The cut-time of Mickey Gilley singing “True Love Ways” carried us along the hardwood, Dad’s calloused palm in my manicured hand. I smiled, even though the tune was unfamiliar to me. I guess it went to number one on the country charts in 1980, the year my parents started dating. Dad would sing it to her in the car as it played on the radio. So romantic, Mom says later. But this was our dance, our slow turn under the spotlight. It didn’t seem like the right fit—know true love’s ways—but what would have been?

Earlier in the afternoon, Dad gave me over, his daughter, his only daughter, his dazzled blue-eyed daughter grinning with confidence over the man she had chosen. I came into the sanctuary my father’s daughter. I walked out of the sanctuary my husband’s wife.

How long had I dreamed of becoming Mrs. Anyone? A boyfriend, a boyfriend, a boyfriend: I wanted one, as long as he would stay around. And then another one, and then I wanted that boyfriend to become a fiancé and that fiancé to become my husband, so I could become Mrs. Anyone. In college, that was the title that mattered: I wanted a partner. I wanted someone I could pour my heart into. That’s what I thought you did after high school and certainly after college. My mom and dad had grown up across the street from each other; she was nineteen when they married and twenty when she delivered her first baby: me. Today it’s ill-advised to marry young, trouble from the start, they don’t know what they’re getting into, a whole life ahead, plenty of time for that, but from where I stood, I felt behind already.

Yes, I also earned a bachelor’s degree. I sought out opportunities to lead and to stretch and to achieve, to do more, earn praise, perform. Dad always said Fugmans aren’t afraid of work, Fugmans are hard workers. He instilled this drive. He was the man who had been my guide. But Brandon was the man I had chosen to walk with me out of the sanctuary, the man who would walk beside me from the altar forward. He brought me a different sort of pride. We had weighed and measured our potential, considered our compatibility, discussed the ways we would raise children, established our priorities. In him, I had found a worthy Scrabble opponent, someone I could adventure with, a man who could say “I’m sorry,” a man who would forgive me, too. For all of that and more, I had chosen him.

Now, Dad held the hand and waist of Mrs. Brandon Wells as we danced. Far in the past, a little girl crawled across his chest and stole his John Deere cap, blue eyes grinning into the face of the camera. She asked for Hooper Humperdink at bedtime again, and now we can all recite it from memory—Pete and Pat and Pasternack, I bet they come by camel back! Back there, too, she watched her mom and dad spin slowly in the living room to “If We Make It Through December,” not knowing then the depth in that melody, not knowing then the weight behind eyes connecting and smiles, what it means to make it through December, together. He taught that little girl the cast of a rod, the slow click and reel after the bobber plunked onto the surface of the water, how to bait a hook with a squirming night crawler. He coached the in-and-out of orange construction cones for hours until she mastered how to parallel park before her final driving test. Whether intentionally or accidentally, he had been preparing me.

Now, we turned slow around the dance floor, each sway a step closer to the last note in the song. Gone was the night we stared up at the cloudless sky on the hill by the old maple and waited for the meteor shower. Evenings swaying in front of a fire pit, turning front ways then back to warm our bodies as we talked about God and faith and family and regret, until the coals flashed red and black, flames dying, then walking slowly into the house to bed. There would be no more creasing wrapping paper in the dry heat of the excavator’s shop on Christmas Eve with him, no more Dad topping off and lifting my bushel basket of corn from the end of a row and spilling it with ease into the bed of the red pickup truck, Dad gunning the accelerator of the snowmobile through the fields with me clinging to his coat toasty in my snowsuit and helmet, Dad showing me the slow slide of a cue stick between thumb and index finger and then the thrust that sent the cue ball breaking against the racked triangle of billiard balls.

All of life before that day squeezed between his dusty calloused hands and mine, a slow turning, slow turning until the end notes began to play. My fingers are my father’s; long and lean, rough along the palms from a summer shoveling mulch, tough where a pen had rubbed and formed a writer’s bump. They were made for work; they were made for pouring your sweat into the thing you loved.

Even over the black tuxedo, fresh trim, and aftershave, I could breathe him in when we embraced, the scent of sweat and sun and earth and oil, “I love you, Sare,” he said.

“I love you, too, Dad.”

“It is a beautiful song,” Mom tells me later, “and we chose it for a beautiful girl.” Sometimes we’ll sigh, sometimes we’ll cry, and we’ll know why, just you and I… Maybe it was perfect. As Mickey Gilley lulled a final “…know true love ways,” Dad spun me out, then pulled me back in, my white dress billowing, the bill of his father-of-the-bride cap shadowing his smile.

•••

SARAH M. WELLS is the author of Pruning Burning Bushes and a chapbook of poems, Acquiesce. Poems and essays by Wells have appeared recently in Ascent, Brevity, The Common, The Good Men Project, New Ohio Review, Poetry East, Puerto del Sol, River Teeth, and elsewhere. Sarah’s poetry and essays have been honored with three Pushcart Prize nominations. Two essays were listed as notable essays in the Best American Essays 2013 and 2012. Her memoir-in-progress on dads, husbands, and the girl between is tentatively titled American Honey. She is the Administrative Director of the Ashland University MFA Program and Managing Editor of the Ashland Poetry Press and River Teeth. http://sarahmwells.blogspot.com.

Follow

Follow