By Beth Kaplan

I’d been looking for her for twenty-six years, periodically Googling both her name and the various ways I thought her workplace might come up. But Penny Harris, my beloved childhood friend, remained invisible. And then last week, I was struck with one of those ideas that spark through the air: although neither of us had ever used her full name back then, I should try it now. Penelope.

In an instant, there she was: Penelope Jane Harris. It was her obituary. She died in August 2019. I was too late.

The memory of the last time I’d seen her haunted me.

•••

“Name’s Penny,” she said. “What’s yours?”

Penny wore thick-framed glasses, her straight black hair cut in a pudding bowl, pale skin erupting into angry patches of red. We met at a neighborhood birthday party where neither she nor I knew how we’d come to be invited. While the in-crowd girls in their frilly dresses gossiped and giggled and played Pin the Tail on the Donkey in the den, Penny and I sat on the turquoise brocade sofa in the living room swooning over our favourite book, Little Women. She preferred intrepid Jo, and I my namesake, saintly Beth. I told Penny that I wept for days after reading the tragic chapter where Beth says goodbye to Jo and then dies with the sun shining on her sweet face.

Penny’s head drooped. She touched her eye, then leaned over and smeared a wet finger down my cheek.

“Real tears,” she whispered.

“Wow. She’s weirder than I am,” I thought, touching the damp on my face, “and she doesn’t care.”

We were soulmates.

This was Halifax in 1962. She was thirteen. I was eleven.

•••

My new best friend lived in a child’s drawing kind of house, a white box with a pointy roof and black-shuttered windows. The windows were always closed, the downstairs rooms spotless and airless. Penny’s dad was tall and hurried, like the White Rabbit in Alice in Wonderland; when Penny introduced us, he bent quickly to shake my fingertips and vanished. Her mother was short and wiry with sharp eyes and a sharp voice. She was always tired, never offered Kool-Aid and cookies like mothers were supposed to. It was clear she wasn’t keen on me, Penny’s only good friend, coming over to play, but she never allowed her daughter to visit my house, I didn’t know why. She ordered us to keep quiet. Quiet!

We tiptoed to Penny’s room and closed the door. Playing outside, even in the backyard, was not an option; my friend was always wheezing with allergies and asthma. She also had eczema, scaly bumpy patches on her elbows and the backs of her knees that made her scratch until she bled, although she struggled not to. “My scratching,” she whispered once, “makes Mum very angry.”

We played with dolls, real ones and paper ones, while we talked about our schools and books and dreams. One day she wanted to tell me a secret.

“Guess what?” she murmured, pushing her glasses back up her nose, as she did constantly. “I was adopted.”

I’d never met anyone who was adopted and wasn’t sure how to respond. “Neat,” I said, holding the shapely new Barbie paper doll we’d been dressing. “Were … were you in an orphanage and everything?”

“Don’t know,” she said. “I heard my real mother had tons of kids already and didn’t have room for me.”

“I hope you were in an orphanage, Pen,” I said, thinking of Anne of Green Gables. “That’s so romantic.”

She turned away. “When I see a woman with lots of kids,” she said, her finger tracing the bright paper dress in her lap, “I wonder if she’s my mother. I wonder if she ever changed her mind.”

I’d often imagined I was adopted. Surely my actual birth parents were nicer than the ones I was stuck with. But deep down I knew that was a fantasy, whereas, it shocked me to realize, Penny really did not know who her birth parents were.

I was a demonstrative girl and wanted to hug her, but I sensed it best to keep my distance. We never touched.

Penny was excited to invite me one Saturday for lunch with her parents. We sat stiffly in the dining room around a large mahogany table, exchanging awkward remarks, while her mother served Campbell’s tomato soup and Kraft cheese sandwiches, not quite enough for the four of us.

My family has lots of problems, I thought, but coming up with food and conversation is not one of them. If I’d been invited back for a meal, I would have found an excuse not to go. But I was never asked again.

•••

Penny and I were mad for figurines. When either of us had saved enough allowance, we’d get the bus downtown to Woolworth’s on Barrington Street and buy a new figurine, small china horses mostly. We gave them names: Violin, Dancer, Fanfare. One day, playing stables in her room, we decided to create special homes for our horses out of whatever we could find. I sprawled on the floor on one side of her bed, and she on the other, in silence all afternoon, making up dramas.

For some time, our afternoons together were dedicated to creating a miniature exhibition that we called Project X. I would decide, say, on a hospital scene and make beds out of cardboard and Kleenex, an operating room of Plasticine and matchboxes, a row of bandaged horses lined up, recovering. Wheezing on the other side, Penny was creating a fairy horse’s treehouse of old cheesecloth dusters, bits of jewellery, wood scraps glued together.

And then we had the thrilling notion to create an entire new world; words and ideas tumbling out, we pieced the story together. I became Helen Foster and she Kristine Foster, orphan twins—fraternal, not identical—whose parents had died in a terrible fire. We’d been sent to stay with our curmudgeonly Aunt Gwendolyn on Foster Island, off the coast of England. In real life, I was sturdy with short brown hair, but my willowy Helen was completely different, with blonde locks cascading to her waist and a delicate face and voice. Everyone loved Helen for her selfless kindness. Penny’s Kristine was a fierce, reckless tomboy always charming her way out of scrapes. “She looks like me,” said Penny, “only prettier.”

Foster Island was mostly fields and woods, so we had our own horses. Mine, Champ, was a golden palomino. Kristine’s Firefly was a pinto. We rode bareback.

Penny and I kept two diaries, one for Foster Island and one for our real lives. At home, I was miserably caught between my parents, who’d separated once and still frightened me with their quarrels. Though I’d been pressed into reluctant service as my mother’s confidante, my little brother, with his blonde curls and dimples, was the adored favorite of them both. The injustice of my exclusion from my father’s heart burned in me. Dad, a noisy social activist, intimated that girls who liked dolls and dresses were boring conformists. He wanted a rebellious tomboy, like my Foster Island sister Kristine.

But I was gentle Helen, and despite the pain caused me by others, I tried to forgive everyone and everything. “Helen,” I wrote in my Beth diary, “is a kind of saint with an indescribable inner radiance.” When my mother yelled that I should clean my room, or Dad smacked the side of my head for some misdemeanour, as he often did, I’d choke back tears and do my best to turn into Helen. In my room, I’d look around at the jumble and murmur, “Oh, dear Kristine, look what a mess you’ve made! I’ll clean it up for you.” And humming softly, I sorted the clothes, tidied the papers, put away the stacks of books. How good it felt to be someone else, neat and serene and cherished.

With all my miseries, however, I sensed in the way Penny crept about her sealed home that her life was way worse than mine. Although she was an only child, I never saw her parents hug her or even talk much to her. Sometimes when she opened the front door, I tried not to notice her swollen eyes. On those days, as I stepped inside, the white house felt darker than ever. But I pushed away any thoughts about my friend’s difficulties; maybe the chilly remoteness I sensed in her home was normal and happened in other homes. In all our time together, Penny and I never discussed our family situations or our parents. I caught glimpses of her real-life diary, covered with her big black scrawl, but never saw what she wrote. We only discussed Foster Island—how we, brave sisters, could thwart foolish, crabby Aunt Gwendolyn to get what we wanted.

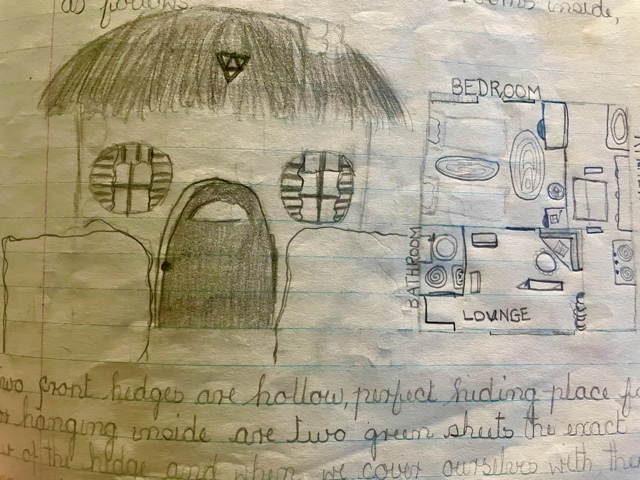

One afternoon, a new treat: Kristine and Helen discovered a perfect little house deep in the forest. We loved being on Foster Island, but the secret cottage was our favorite place. In my Helen diary, I drew a picture of it, hidden in the trees, with a thatched roof and bright sunny windows. There were matching hooked rugs in the bedroom, beside Kristine’s bed and mine. Champ and Firefly grazed in the field of wildflowers outside the front door.

By the time Penny turned fourteen, she had a bra and her period and had discovered pop music. “You don’t listen to the hit parade?” she asked one day, and I boiled at the condescension in her voice. She began to spend her money not on figurines but on 45s, which she insisted on playing for me, snapping her fingers. I told her “Louie Louie” was the stupidest song I’d ever heard. “I guess twelve is too young to get it,” she shrugged.

The change in my friend upset me. But still, most weekends, she and I sailed to our island and played there all day.

When Penny told me her father had taken a job in Victoria on the other side of the country, we both cried real tears. But immediately, we turned our separation into a story. Kris, we decided, was being sent far away to a special boarding school, but her unfortunate twin couldn’t go. Helen’s faithful German Shepherd had chased a rabbit onto the road, and she’d thrown herself in front of a speeding car to save him. Legs crushed, she was now confined to a wheelchair. But she bore her disability with infinite patience.

Penny and I swore to write to each other forever, and for a while we did, one letter from friend to friend, and another, in the same envelope, from sister to sister. I wrote to Penny that school was a drag and I was making a Hayley Mills scrapbook, and Helen told Kristine she was gaining strength in her legs and “I might even walk with crutches one day!” There were also notes in Aunt Gwendolyn’s flowery script, hoping her far-away niece was doing her algebra homework and eating her lima beans.

Envelopes from my friend included scribbled missives to Aunt Gwendolyn from despairing teachers at Kristine’s school, while Penny wrote about the actual boarding school her parents had decided to send her to, which she liked a lot and where she’d made a friend. And then came the day Penny sent only one letter. “I can’t do Foster Island anymore,” she wrote. “I’m too old for little kid crap.”

For a moment, I couldn’t breathe. I was not ready to be exiled. Just a bit longer, please, I wanted to beg.

A few days later, I carefully hand-printed and mailed an official-looking document. “To Miss Kristine Foster,” it said. “We regret to inform you that Foster Island has been destroyed by a long dormant volcano. Everything on the island was buried except for a burned and twisted wheelchair. Please accept our sincerest apologies, and best wishes for your future.”

Penny did not reply.

•••

More than three decades later, I was invited to Vancouver to act in a play. A forty-five-year-old single mother, I was also a former actress attempting a comeback. One night, waiting for me at the stage door was a familiar form with dark pudding bowl hair, pale blotchy skin, and black-rimmed glasses. I knew her instantly. “Penny!” I exclaimed. “Real tears!”

We met for coffee, spilling over with fond reminiscences of Project X and Foster Island. I told her about the confused decade of my twenties, my marriage and divorce, my two children and recent work as a writer. Despite all those vivid fantasies, I said, I now write only nonfiction because I value true stories most. It has taken a long time and a lot of professional help, I said, but I feel pretty good about life.

At forty-seven, Penny had never had a partner and had always lived alone, but she enjoyed her work hunting down tax cheats for Canada Revenue. “I think I might be gay,” she said, looking sharply at me to see if I was shocked, “but I’m really not sure.” I told her many of my artsy friends were gay, and I’d even explored, briefly, if I was too. Another bond.

Waiting until the waitress had refilled our coffee cups and left, my friend leaned closer and told me softly that her mother had recently died.

“After the funeral,” she said, her face expressionless, “Dad finally apologized to me for what happened during my childhood.”

As she took a breath to go on, I knew. I knew what she was going to say.

“There was something really wrong with Mum,” Penny said, pushing her glasses back up her nose, her voice monotone. “I mean emotionally, mentally. She liked to torture me. My playtime with you was one of my only escapes.”

My stomach heaved as my friend talked about years of anguish at the hands of her mother. “She locked me in the basement—sometimes I didn’t even know why,” she said, as I shook my head in horror. “She beat me and mocked me when I cried. Or it was just that she wouldn’t give me anything to eat. No dinner for you for a week, she’d say.”

“Oh, my friend,” I said, appalled.

“Before I met you, my parents adopted a little boy, Sean,” she told me, chapped hands gripping her coffee cup. “He was the joy of my life. I’d run home from school to take care of him. Then one day, I got home and Sean was gone. Without a word of warning, my mother’d sent him back. She told me she couldn’t cope with him,” Penny said, “and if I wasn’t careful, the same thing would happen to me.”

I writhed in my seat, heartsick. “I should have done something, helped in some way,” I cried.

“Nobody knew what was going on, Beth,” she said, so quietly I could hardly hear. “No one.”

I made a move to hug my friend, to convey concern and care, but the prickly barrier surrounding her was as impenetrable as ever. Perhaps now as then, I thought, admitting vulnerability, allowing in compassion, would hurt too much.

We pledged to renew our correspondence—not by email, but by real mail, like always—and after my return home, the letters began to flow again. Being in touch with a treasured childhood friend, reading her familiar black scrawl, gave me immense pleasure; something vital and long missing had been found. I smiled to think how wise we’d been back then, two intense, unhappy girls who’d imagined themselves, with such vivid detail, into a kinder place. Though still anxious and hyper-sensitive, I was well on my way to feeling truly at home in the world. I hoped my friend was as well.

One day she wrote to say she had exciting news: she’d met a wonderful man and was madly in love. He was struggling financially, she said, with an unfair, demanding ex-wife and two children; last year, through no fault of his own, he’d lost his job. She had invited him to live at her place and would gladly support him until he got back on his feet. She was sure he’d soon find a job, and her life would be happier than it had ever been.

“Do you remember our secret cottage in the woods?” she wrote. “I feel like I live there now.”

“Yikes, no, Penny,” I said out loud. How could I not be concerned by what she’d described, her lonely susceptibility to what sounded like a manipulative man? Should I say something? I’d failed to help her a long time ago and must do so now. But how? Finally, thinking I might be the only person she trusted, wanting above all to protect her, I wrote a gentle letter, begging her to be careful with her heart.

I never heard from her again.

•••

After all those years of wondering about and trying to reach my friend, I wept to read the brevity of her obituary: Penelope Jane Harris, August 31 1948 – August 19 2019. There were no messages of condolence. I was desolate. If only just once I’d been able to offer an embrace, to express my love, my gratitude for her courage and her imagination and her friendship.

And then, by the miracle of the Internet, I discovered something else: a B.C. woman named Penelope Harris had donated two parcels of land to a local First Nation. I clicked further and found a series of photographs. This Penelope Harris had very short white hair and no glasses. But I knew the cheekbones, the eyebrows. Her lively face.

Penny had bought two small parcels of land near Prince George as an investment; decades later, the area still undeveloped, she’d given the land to the Lheidli T’enneh First Nation. In April 2019, she travelled from her home in Abbotsford to Prince George for a ceremony during which they’d celebrated her generosity.

“I feel there is nothing we can do to fix all the things we’ve done wrong as a society to Canada’s Aboriginal peoples,” she said in a speech to the local press. “The line we were all fed about what the Canadian identity was, how great the Canadian story was, that has now fallen to pieces for all to see. Good. We were all duped. We’ve been lied to for generations. But we know that now.

“What are we doing now to make things right?” she concluded.

In his response, the chief called her gift “reconciliation in action.”

“We will always think of Ms. Harris as one of us,” he said.

Penny died four months later.

The First Nation community gave my friend a beautiful black and red hand-embroidered jacket. In the photos, she’s wearing the ceremonial coat, and her face is radiant.

•••

BETH KAPLAN, a former actress, has taught memoir and personal essay writing at two Toronto universities for decades. She’s the author of four nonfiction books: two memoirs, a biography, and a guide to writing memoir that’s the textbook for her courses. Her next book, an essay compilation, is nearly finished. Her website and blog are at bethkaplan.ca.

Follow

Follow