By Jenny Poore

The first time I got the instructions for how to avoid burning in hell, I was five.

I sat on my older sister’s bed as one of her friends asked me, “Are you saved? Because if you’re not saved, you’ll never get into heaven and you’ll burn in hell forever and ever. It’s easy to be saved though. Just close your eyes and repeat after me: I accept Jesus Christ as my lord and savior. Just do that and you won’t burn in hell. See? Easy!”

I looked at her skeptically through half-closed eyes and only mumbled the words, hedging my bets because that’s what children do when told things by older, supposedly wiser people but don’t fully buy it. I was a naturally suspicious kid, I suppose, and her curly perm and blue eye shadow didn’t inspire confidence. Afterwards, she nodded her head and popped her gum loudly, satisfied with her work. My teenage sister, having had enough of me crashing her space, kicked me out of her room and changed the record on the white stereo system I coveted. I clearly remember not understanding what had just happened, but I hung onto the words “Jesus” and “hell,” those two things feeling like the most critical parts of whatever lesson I had just learned.

I grew up in a non-religious family in one of the most religious places in America. Lynchburg, Virginia in the 1980s was an Evangelical Christian mecca that is second only to Utah for the religious devotion of its residents. The disaster smash of the Reagan years and the rise of Evangelical Christianity in the political arena happened literally in my backyard as an influx of thousands moved into my town to be closer to Moral Majority rock star Jerry Falwell’s Thomas Road Baptist Church and his freshly minted Liberty University. Our once-quiet street was suddenly three deep with cars on Sunday mornings and Wednesday nights. When people couldn’t get into the too-packed services, they’d sit parked at our curb and listen on the radio, completely overdressed for their Pintos and Datsuns, smiles plastered on their faces as they sang along to the hymns and nodded to their preacher’s words.

It was impossible to get away from the proselytizing. After-school clubs at friends’ houses always started with bowed heads and a prayer, and random teenagers would ask the status of your soul while you swung on the swings at the playground. As the church grew, it steadily bought up the beautiful old brick houses on my street and filled them with missionaries, families from other towns with five, six, ten kids who were homeschooled and who went door to door passing out small cards with bloody fetuses on them warning of the evils of abortion and whom to a fault could barely read. I never understood why they didn’t have to go to school, but I played with them because we were kids and they were fun and I just always ignored the warnings of what would happen to my eternal soul if I didn’t accept Jesus Christ as my personal lord and savior. You get used to being told you’re going to burn in hell. After a while, it’s just static.

But it was a static that itched and was omnipresent. We did not go to church, but everyone we knew did. As I got older, there were lock-ins and youth groups, and Scare Mare, the Thomas Road Baptist Church–sponsored horror house that is still a Halloween tradition in my town. Before it turned overtly political with rooms like The Abortion Room and The Drunk Driving Room, it was actually pretty fun, a generic scary house with strobe lights and people jumping out at you in masks, harmless and spooky and something to do in a town with not a lot to do.

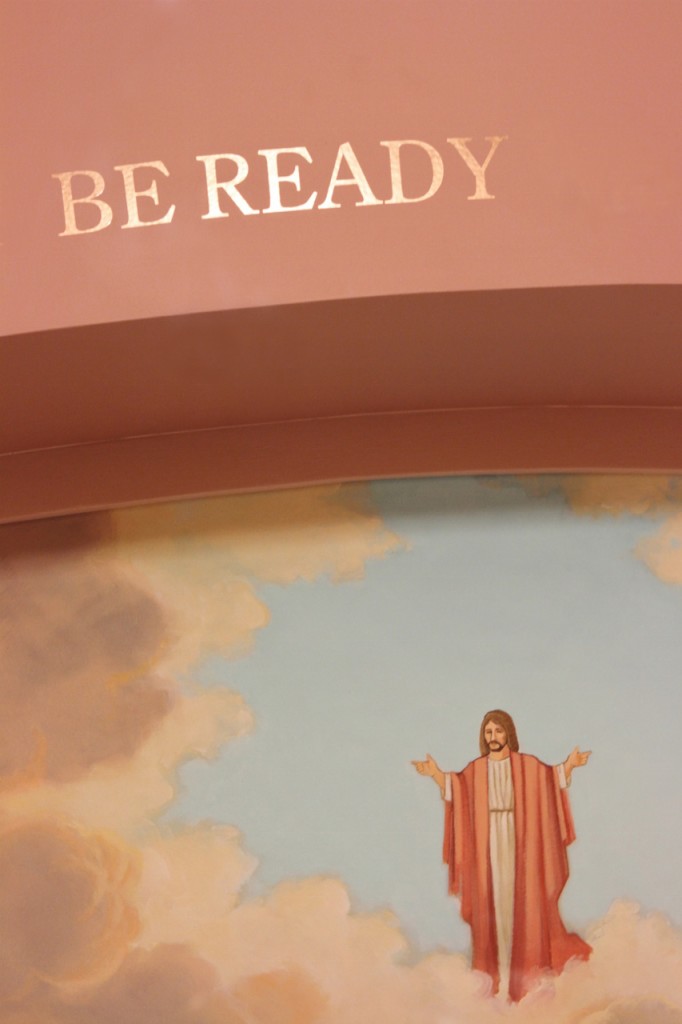

The last room of Scare Mare was always the scariest because it was after you’d left the haunted house completely. Puffed-up young men in polo shirts and crew cuts would line the path back to the parking lot with flashlights repeating in a disturbingly stern unison “Last room of Scare Mare, folks, last room of Scare Mare…” as they ushered you into one in a very long row of musty old army tents. It was always clear that this room was not an option. All attempts to skip it and just go back to your car felt forcibly cut off. I never knew anyone who got away with avoiding this last room even though we always talked about how we were totally not doing that, there’s no way they can make us go in there, the entire time we waited in line.

I was around twelve when my sister and her boyfriend took me with them the first time. As we left the haunted house and were funneled into the ancient army tents, my sister’s boyfriend just kind of shook his head in a “let’s get this over with” fashion and we took our seats in the metal folding chairs. My experience sitting in a church service was wholly limited to the rare Easter Sunday with my grandpa, some light singing and a short service and he’d slip me candy bars he’d sneaked in in his pocket. I was unprepared for the frothy and furious young man who stood at the front of the tent shouting at us and regaling us with the horrors of a forever in the fiery pits. “DO YOU WANT TO SPEND ETERNITY IN A PLACE LIKE THAT???!!!” He screamed at us, reminding us of the perversions and terror of the haunted house we’d just exited. “IF YOU DON’T ACCEPT JESUS CHRIST AS YOUR SAVIOR, THAT IS YOUR FUTURE!”

He went on and on about pain and death and depravation and was generally terrifying and foamy-mouthed until my sister’s boyfriend, recently home from the Marine Corps, and generally very strong and in-charge looking, spoke up and cut him short mid-sentence. “Hey!” he shouted. “You need to calm down. There’s kids in here.”

Slightly chastened, the lunatic preacher man slowed his roll and transitioned into the final part of the whole experience. “I’d like everyone to close their eyes and bow their heads…” He then gave a much quieter but no less passionate description of heaven and the story of Jesus and how he’d died for us and if you were a grateful and good person you’d just thank him for that by accepting him as your lord and savior so you could spend eternity among the peace and goodness of heaven and be happy forever and thank you for coming to Scare Mare folks, God bless you all, drive home safe.

I’d peeked through my eyes when our heads were supposed to be bowed and seen that, for the most part, everyone was doing as he’d told them to do, but I did spy a few hold-outs like me, others who were sneaking a look and just waiting for their chance to escape. I marveled then at the braveness of my sister’s boyfriend to challenge the preacher. You mean you can do that? You can tell people like that to stop yelling at you? If you can do that, then does that mean we don’t really have to come in here? Do I not have to bow my head even though people are always telling me to? I had questions.

Despite years of being told I’d burn in hell if I didn’t Accept Jesus Christ as My Personal Savior, I never decided to accept Jesus Christ as my personal savior. Even as a kid I saw the fallacy of the whole process. If he’s so nice, why would he send people to burn in fiery pits forever just because of some loophole clearly based on vanity? That never sounded like something a personal savior would expect from you. Beyond that, though, I steadily became aware that there was always a streak of fear and smallness that ran through the hundreds of exchanges I’d had with the True Believers in my life. It was nothing I wanted to be a part of. I can still count on two hands the number of families that consider themselves Christian who actually act in a way that the Christ I’ve read about would be proud of. Two hands in this town of thousands upon thousands of families.

I grew up with what I now know is a siege mentality, this feeling that my universe was occupied by hostile forces who were not only not on my team but who openly and publicly proclaimed that terrible things were going to happen to me and my kind and good-hearted family if we did not jump through their very specific hoop. It’s a terrible thing to be told repeatedly in public and in private and by strangers and friends alike that you are not worthy and will be punished horribly for it. That does something to you down deep; it changes you and others you in a very specific way. I’m not sure at what age exactly that it finally happened, but at some point I embraced this “otherness” and made it my own. I have no religion, I don’t want a religion, and I am completely comfortable telling anyone that.

Home is home. though. That nightmare Halloween house is staged on the grounds of the long-gone cotton mill where my grandfather’s people all worked and lived and raised their babies. The community of Cotton Hill is still a vibrant one, where people share stories of the weaving room and the mill nursery and birthday parties on Carroll Avenue. Our memories are long. Despite the tidal wave of evangelical Christians that poured into my town starting in the eighties, I’ve always been quick to claim ownership. Though so often it seemed like I didn’t fit, here I refused to be run off. “It’s them who don’t fit,” I’d think, “I was here first.” So, like my own parents, I parked my little family right behind Thomas Road Baptist Church where for a long time after old Jerry still preached and dared all comers to try to make me feel less than, try to make my children feel less than, woe unto those who might try.

Walking my eight-year-old son home from school the other day, he said, “Michael asked if I believe in God and I told him no, and he said I was going to burn down there forever.” I looked at him and he was pointing to the ground with a smile on his face. We laughed about it because I have done my best to make my children bullet-proof in this city we live in. I have prepared them so they know that there will be people out there who will tell them mean and untrue things so it doesn’t bother them like it did me when I was small.

“Well, that wasn’t nice of him. But you know it’s not true, and you know he can’t help it. He just doesn’t know any better.” My son smiles and nods at me but he always looks bummed when this happens, because it happens and happens and happens, as it happened to his older sister, too, and it will to his younger sister as well. He is a kind boy and he would never assume awful things to happen to others for no good reason. A god like that makes no sense to him. He figured out the falseness of it long before I did.

Homeschoolers keep their kids out of our public schools because, ostensibly, it’s my children they should be afraid of. My godless, secular humanist children and their evil ways. But I learned a long time ago and I continue to see now that the pressure so often moves in only one direction. I am certain that my children aren’t roaming the halls of their schools shouting, “God is dead! God is dead!” The lack of love and generosity extended to those of different sexual orientations or religious beliefs or other ways of life is still blatant and harmful. But call them out on their unwillingness to just let others live their lives as they choose and you’re persecuting them for their religious beliefs, as if a religion based wholly on the persecution of others is a religion at all.

But not all is lost. Whenever my kids come home and tell me the latest story of how they’re going to burn in hell, I don’t just remind them of the falseness and foolishness of the statement. I also take time to remind them of the Christian families we know who are good and love us and all others without reserve, those who’d never tell us that we’ll burn in hell. It took me a long time to realize that those Christians really are out there, and if I believed in a god, I’d thank him or her for them. Because those are the people who remind us of the possibility of good in a world that so often promises us otherwise. Who remind us to not pick up and throw back the stones we so often find at our very own feet, who would never ever force us into a musty old army tent to shout.

•••

JENNY POORE writes about parenting, public education, politics, and occasionally things that do not start with the letter “P”. Her work has most recently appeared in xoJane, Mommyish, Dame Magazine, and Role Reboot. You can follow her on Twitter @Jenny_Poore and at her blog, Sometimes There are Stories Here.

Follow

Follow