By Robin Schoenthaler

I was forty, and single, and pregnant, and jubilant. I blossomed during a perfect pregnancy and then proceeded to give birth to a beautiful baby boy I named Ryan Peter Schoenthaler, eight pounds twelve ounces and twenty-one gorgeous inches long. He died nine days later in my arms, still and cool.

I buried that boy on a sunny hillside in a tiny casket designed to look like a bassinet, and by the time I stumbled out of the cemetery, I was a dead woman walking. Some days I couldn’t keep my eyes open; other days I could barely speak. I dreamed in adjectives: impossible, unbearable, unimaginable; I woke up with verbs: pulverized, imploding, eviscerated.

Two years later, I gave birth to a boy named Kenzie James. I got through the pregnancy and birth through denial, plain and simple, with one permanent pricetag: nine months of total amnesia. Of that period of pregnant pause, I remember OJ Simpson and I remember grinding my teeth, and that is really all.

Three miscarriages and three years later, when my last son came along—Cooper Craig Schoenthaler—I was wholly awake and fully attentive and I remember everything. Of the six pregnancies, I am left with one birth story.

Cooper was delivered by Cesarean section. An average C-section takes six or seven minutes from incision to delivery; Kenzie’s took an endless half-an-hour; Cooper, eleven minutes. Eleven minutes to a lifetime.

I lay there while they opened me up again, floating along the arc-line that had gradually and irrevocably led me to this scene—lying flat on my back in a yellow room with bright lights. I was a woman physician under the care of women who started out just like me, women who struggled over books and tests and money and hostile men in positions of power for years at a time and who now put their bodies and souls on the line.

I remember my obstetrician Sharon coming to my hospital room at midnight to attend Ryan’s brain-dead baptism. I picture her holding my hand in the NICU that night and then again and again over the next five years. I think of all the phone calls: I would sob and she would let me make any appointment any time as I worked through the surviving of survivorship.

I think of all the tables I have laid on and all the doctors I have seen—a long line, a stately procession—giving me good news and bad news and no news at all. I think of Ryan’s delivery and his death. I think of how I lifted his body straight up above me, offering him to the sky. I think of Sharon two years later holding Kenzie aloft, in triumph, a giddy elevation of child-spirit, a peak moment, a crystal. I think of the dim light in Ryan’s NICU room where his soul sailed away, and the bright lights in Kenzie’s delivery room when his soul sailed in.

I think of the night light that Kenzie uses—how at three he is already such a singular little person who wants to look at books alone at night, how his soul is full of light and always has been. I feel the presence of both Kenzie and Ryan very distinctly within me, as well as a whole line of women who have given birth before me—my grandmothers and my friends, my mom and all the bereaved women in books and on buses.

I listen to the heartbeat monitors and think of Ryan’s heartbeat ceasing and Kenzie’s frantic heartbeat when he’s feverish and the roaring in my ears each time I miscarried and I can’t help but compare them to the steady beat-beat-beat that is my own heart’s rhythm in this room at this moment.

It’s a long eleven minutes.

Then I hear Sharon start to croon. In seemingly an instant, she again holds one of my sons aloft in the light. The overhead lamps create an aura, a halo, an embrace and I experience blindness reversed as the light heightens every pore and every limb and Cooper is outlined in beauty, screaming shrieking bloody beauty. He is alive, he is aquiver, he is a soul.

They bring him to me wrapped up and warm. I get my first good hard look at him: he is red-faced and dumbstruck, and I am the same.

I reach for him. No one says a word. The room is quiet; it feels like an altar. There’s no heart monitor machines now, no barking loudspeakers, just the murmuring of Sharon and her partner, and the nurses counting sponges. I kiss Coop over and over—his perfect cheeks, perfect skin, perfect neck. He turns to me when I speak.

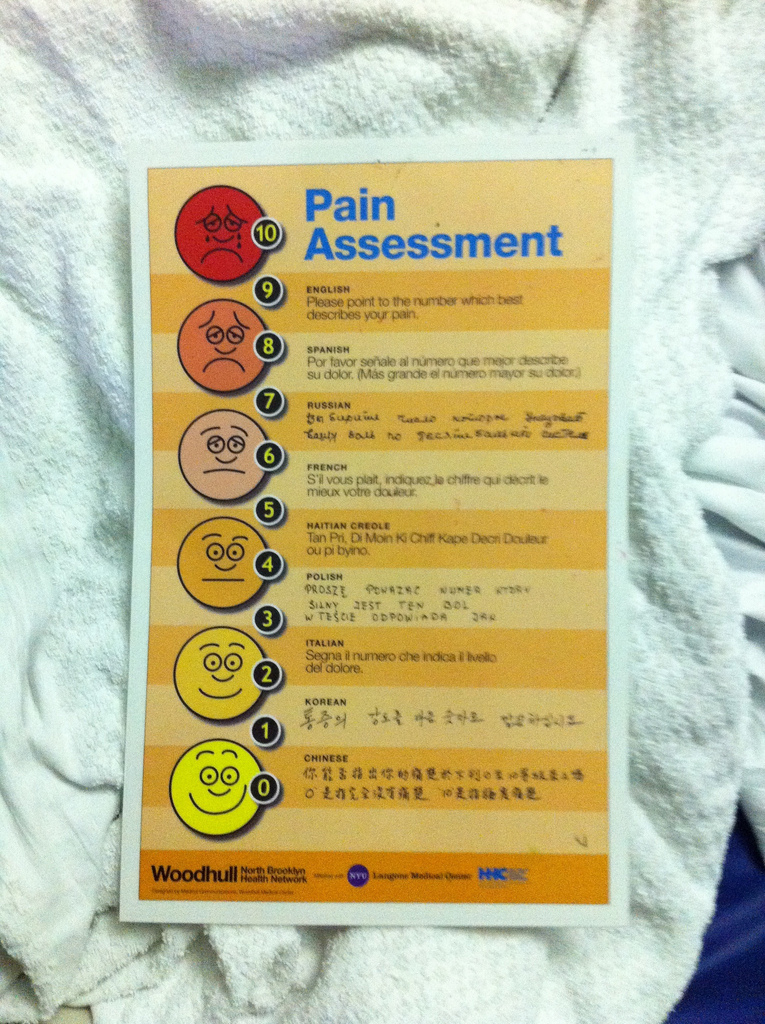

I lay there with this miracle in my arms, flooded with all that can happen over the course of half a decade. I remember the long period after Ryan’s death when a pain-free interval seemed impossible, when anguish never ended and never waxed or waned.

But I realize, lying there, that somehow, somewhere, something carried me through. It is too strong to call it “hope”: there was no hoping back then. It’s too strong to say it was anchored in me—it was not. But it must have floated, in and out, with the moon, or with the seasons, or maybe with each breath.

Because something helped me hear the muffled words that sometimes bounced off the sheer rock cliffs of my pain. I began to hear the voices in the cemeteries I visited—voices of mothers who murmured that if I could just keep breathing long enough the tunneled darkness might begin to lift. I began to see the anguish of my cancer patients in terms of cells defying death. I began to connect myself to a humanity bound up with suffering—plague victims, war dead, road kill, religious martyrs, and most of all a long line of women who had keened over children in caskets.

Something had taken hold of me. It wasn’t optimism or confidence or faith in an equitable universe—that was gone and would never come back.

It was much fainter: a tiny turning, a whispered murmur, a miniature red berry lying deep and dormant. But the berry dropped a seed and the seedling took. A tiny bud appeared and on it there must have been a drop of dew, and that was where I let that little thing that must have been hope float. I never touched it, I never named it, I really never even knew it was there. I just let it float. I let my hope float. I let my hope float on an impossibly tiny bud and now I had another son, I had two more sons.

They move us to the recovery room where it is dimly lit and quiet. Cooper nurses. I am pain-free and at a level of peace that is hard to describe to this world. I curl up on the gurney in the darkened recovery room, all dreamy sated senses.

Eventually the nurse and I begin to chat. She remembers Ryan well. “Every time I pass Room 428 I think of all the flowers you left behind,” she tells me. Then we coo about Cooper, how beautiful he is and already such a good nurser and so alert and connected and smart.

She tells me then about her own difficulties with conceiving, her doubts and how frightened she has become. I can so completely relate to this young woman at the beginnings of yet another long trail. She says to me, “We’ve tried so hard to have a baby, but I’m afraid to keep trying. How did you keep your hope alive?”

I start to tell her, but I hesitate. I’m suddenly tired beyond imagining, my eyes and limbs feel weak and I am nearly asleep. I murmur, “Just let it float.” She says, “Hope Floats? Isn’t that a movie?” and I giggle into the pillow.

Lying there laughing, I feel them like a flash flood, the raw and precious lives that led us here: the lives where pain has a beginning but anguish has an end, where seasons start and berries fall, where there are voices that can pierce the darkness and where cells that split can mean life in one year and death in the next and where there are webs that connect us with our ancestors and that in the darkest winter there are buds that can act as cradles and that hope may not spring eternal but that it can absolutely float.

•••

ROBIN SCHOENTHALER is a writer/mom/physician (the order varies by the day) who lives outside Boston with her sons Kenzie and Cooper. They are now seventeen and fourteen, and Ryan, had he lived, would be a freshman in college. Her website is www.DrRobin.org.

Follow

Follow