By Jody Mace

Tarzan. Tonto. Tuvafana. These were the passwords that my father used for all his accounts. I learned this during the stage of his dementia when I had to manage his accounts. Guessing his passwords wasn’t too hard. I just had to go through these three possibilities and maybe add a 1 or a 2.

The bigger mystery was what the hell Tuvafana was. Tarzan and Tonto were self-explanatory since he was a fan of Tarzan and The Lone Ranger. But what was Tuvafana? I asked him right away, but it was already too late. He didn’t remember.

I thought it might be Hebrew, since Tuva is close to the word for good, Tov.

My dad had been interested in languages all his life and had many stories, which I didn’t necessarily believe, about his surprising proficiency at unlikely languages. There was the time as a boy that he was visiting a friend, whose family was Greek, and had impressed the boy’s mother by speaking Greek. Or the Chinese restaurant where he spoke fluently in Mandarin, and in Cantonese, just in case.

But I had no clue about fana.

During the years that I was managing my father’s accounts, I made many attempts to solve the mystery. Was it a character from a book? The name of one of his relatives?

But the mystery remained.

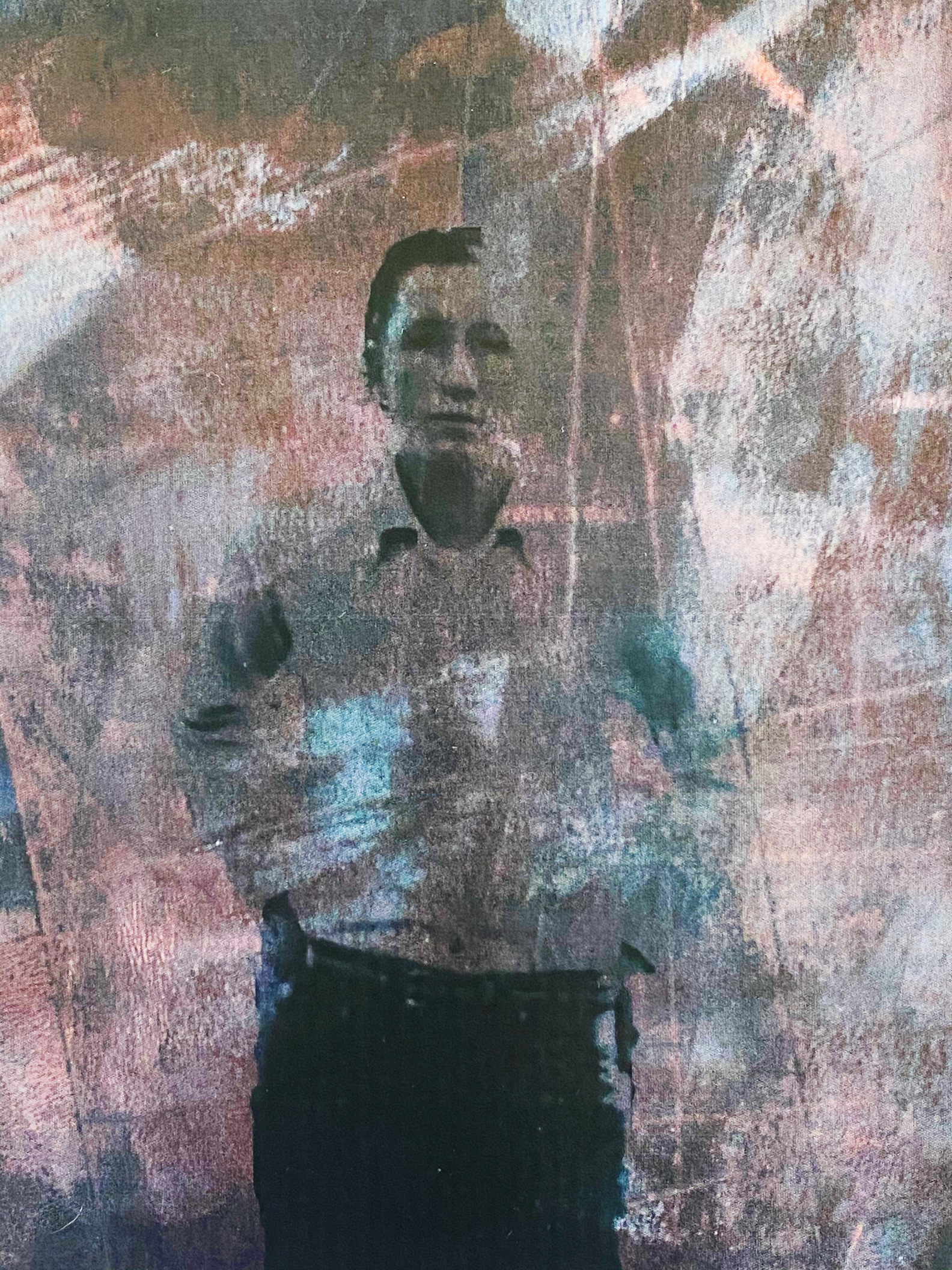

One thing about having a parent with dementia is how much of the past becomes a mystery, and how abruptly it seems to happen. It made me realize how little I had tried to get to know him when he was mentally whole. My life with my father was dominated by his stories, but they were both endlessly repeated and apocryphal. I think that over time I was worn down by his narrative and didn’t really have the energy or desire to start up more conversations. But as his dementia progressed, he grew quieter and I started asking questions to fill the void. Sometimes he talked. I have a collection of voice memos on my phone of the conversations that did take off. But a lot of times he didn’t want to.

I was losing my only remaining parent, little by little, and with him was going all the knowledge of a different, but related world, where people who looked like me spoke Yiddish and wore long dresses and ran a corner grocery store. Which relatives did he visit in New York as a child? What led to the failure of his family’s grocery store? Why did his father have different countries and years of birth on his passport and life insurance application? Nothing huge. Just little things that started out as facts and then became questions. And then, when there was no way to answer the questions, they became mysteries.

•••

It’s a well-known phenomenon in my family that people tell me everything. I might ask one casual question, and complete strangers tell me about their first marriage, their cigar business, the novel they’re writing, the time they were homeless. I think it’s because I find people interesting, and they can tell.

But somehow that interest didn’t extend to my father, at least not in action. I guess I thought I’d have time for questions later, and then I didn’t.

•••

Solving mysteries has got to be one of our most fundamental drives. From Encyclopedia Brown to Nancy Drew to Sherlock Holmes to Jessica Fletcher, when they solve a mystery, they solve it. There’s no half-assery involved, no lingering doubts. That’s the kind of mystery solving I like. You find a hidden staircase. You catch the thief as he tries to execute his heist. You ask that one question that forces a confession. Everything clicks into place like a puzzle that can only be solved one way, or a meticulously maintained old clock. Clean.

•••

As my father’s dementia progressed, not only could I not solve the mysteries I knew about, but there were more mysteries every day. He often told me about things that were clearly dreams, or tv shows, but he thought they had happened.

I was learning to meet him where he was. This is the way you’re supposed to communicate with people with dementia. You don’t tell them that they’re wrong. You just let them talk and respond to what they say, as if it’s real.

He was in a continuing care facility, but in the “independent living” part of it. I knew that he would need to move to a memory care unit, or something like that, with more security, but, when? He actually functioned just fine in his apartment, with lots of help and supervision. I was there a lot, and there was also someone who came in twice a day to make sure he took his pills, and someone else who helped around the apartment a couple times a week. He told me every day how much he loved his apartment, especially the recliner I had bought him. It truly was the happiest I’d ever known him to be.

When is the exact moment that it’s best to make someone measurably safer but at the cost of making them immeasurably sadder? He seemed okay for now, but I knew that the decision was bearing down on me. I envisioned the decision like two arcs on a single graph. When do they cross? It’s a wrenching calculus.

One August morning I got a phone call from my dad. He said that he had returned my magazine to the library but had forgotten to put my note in it. There was a library in the facility where he lived, and he regularly borrowed magazines from it. I hadn’t borrowed a magazine and I hadn’t written a note, but I said, “Thanks for returning it. Don’t worry about the note. It wasn’t important.”

I had met him where he was. He seemed relieved, and I felt good that I had responded to him kindly.

Then, late in the afternoon, someone called me from the front desk of the care facility. Nobody had seen him that day. Was he with me?

When an 86-year-old goes missing, it’s an emergency. He had never walked away from the facility before. Not once. Not a step. He couldn’t have been less interested.

It took several hours under the blistering sun, and the help of a what seemed like a whole precinct of police officers, but it was ultimately the GPS signal from his Jitterbug phone that led us to his body. He was lying in a clearing in an overgrown wooded area near his apartment, with his hands crossed on his chest, his eyes open to the sky.

I don’t think anyone comes out clean when their parent dies. There’s always something to feel guilty about. But when you were the person who was supposed to keep them safe, and you didn’t, no matter what the reason, it hits hard.

I think about the things he missed in the two years that he’s been gone. He missed his granddaughter’s Bat Mitzvah and his grandson’s college graduation. He missed the isolation of the pandemic, which he would have hated. He missed Trump losing the election, which he would have loved. Mostly, though, he missed the free fall of decline he was about to experience, and the loss of freedom. There was some medical event, maybe a mini-stroke, that had confused him and set him to walking. He missed going into a nursing home or hospital. Maybe he did this just the way he wanted to. Who knows.

“Who knows?” seems to be both the question and the answer to everything, the only response to a mystery that will never be solved. Who knows what he was talking about when he called me about the magazine? Who knows where he was when he called me? Who knows where he thought he was going? Who knows why he lay down in that clearing, looking exactly as if he was going to take a nap? Who knows.

I wish I had tried harder to solve his mysteries years ago, when they would have been easier to solve. Maybe the biggest mystery isn’t even about him. Maybe it’s about me—why I didn’t try to know him better when I could. Why I assumed that we were just too different to really connect.

I’ve been learning Yiddish for a few months. When I work on it I think of him. Although I doubted some of his stories of language acumen, he was definitely a fluent Yiddish speaker. His family spoke it when he was growing up. I keep wondering if I’ll come across Tuvafana but I haven’t. I’ve worked my way through “food,” “friends,” “complaining,” “leisure,” and “office,” but no Tuvafana.

The other day I googled Tuvafana again, and this time I got a hit. It wasn’t a definitive explanation. It was no smoking gun, no invisible inked message with a code I cracked. I don’t know if this was actually something my dad, a lover of languages, once came across and then forgot where it was from. I don’t even know if the translation I found was correct. But for now, I’ll take it.

It was a word in someone’s Facebook status, in an unfamiliar language. I typed it into Google Translate, which identified the language as Shona, a Bantu language spoken in Zimbabwe.

The translation was “We are the same.”

•••

JODY MACE is a writer and website publisher in Charlotte, North Carolina. Several of her essays have appeared in Full Grown People.

Follow

Follow