By Lori Jakiela

My bio-brother says his father was in the movie business. He says his father played piano. His father, my bio-brother says, was an amazing piano player, long fingers, a real natural.

Bio is what my brother and I sometimes call each other to make sense of things. It’s hard to find language for what we are and how we feel about it, so sometimes we don’t bother at all.

I’m forty by the time my brother and I meet. He’s a few years younger. When we’re together, my brother and I like to compare hands. We press our palms together, measuring. Our hands are big, long-fingered.

“We get it from the old man,” my brother says.

•••

My brother and I weren’t raised together. His mother gave me up for adoption before he was born. His father abandoned his family for Hollywood years ago.

My brother’s mother is my birth mother, but when I say mother and father, I mean the parents who raised me. I say “real.”

When my brother says mother, he means the mother who raised him, a woman I’ve never met. When my brother says father, he means a stranger.

•••

My brother asks if I play piano.

I tell him I do.

He says he hopes I’ll play for him some time.

I tell him I will.

•••

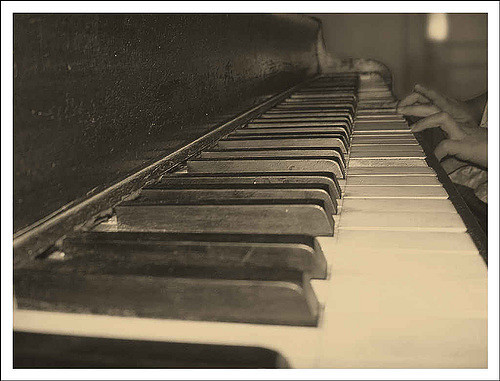

Soon my brother and I will be together in my basement, and I will play songs on the piano I learned on as a child. The piano is over thirty years old, an upright Kimball, but the keys are good. My mother, the mother who raised me, kept the wood polished with oil soap so it still shines.

I do my best to keep it up.

I polish it when I can.

I play my brother “Begin the Beguine,” my father’s favorite song. My father, the father who raised me, was a singer, before the war, before the mills, before he got bitter and sad and stopped singing.

Once he won a contest and got to sing on the radio in Braddock, Pennsylvania, and for a while everybody knew him as the boy who sang on the radio.

Then they forgot what song it was he sang.

Then they forgot it was him who sang it.

Then they forgot my father’s name and how to spell it.

Then they forgot my father ever sang at all.

The song he sang was “Begin the Beguine.” The story goes, my father cut a record that day as part of his prize, but I never saw a record. No one did. My father must have kept it hidden or destroyed it.

Or maybe there never was a record. Maybe that was just a story. Maybe there was just that one time in the radio studio, one take, the D.J. picking his fingernails, saying, “This is it, kid. You got five minutes.”

My father always thought the song’s title was “Begin the Begin,” as if any minute his life would start over, as if any minute it would be good.

I tell my brother this and laugh, even though I think it’s sad.

It’s one of the saddest stories I know.

•••

I play my brother another song—“Somewhere My Love,” my mother’s favorite, the theme song from “Dr. Zhivago,” a sap story set in the Bolshevik Revolution.

I have always hated this song.

My mother would make me play it over and over for guests.

I tell my brother this story, too.

I tell him about the time my mother made me play it for her cousins, Dick and Stella.

“Dick was a bastard,” I say.

“I know a lot of bastards,” my brother says.

“Me too,” I say.

My brother says, “I know that’s right,” and puts a hand up for me to high-five.

•••

I’m sixteen, and Dick and Stella have just pulled up in their paneled station wagon. They’re staying for the weekend. I hear Dick say, “Jesus fucking Christ,” and I hear Stella apologize three ways.

I’m hiding out in my room when I hear my mother call, “Oh, Lori baby. Come say hi to Dick and Stella. Come play ‘Somewhere My Love’ for us.” It’s her sing- song, welcome-to-my-perfect-home voice.

My mother watches a lot of old movies. She’s spent a lot of money on me—piano lessons, dance lessons, doctors, clothes and food. What she wants every once in a while is to impress people—in this case, Dick and Stella. What she wants is for me to come out and be, just once, a perfect daughter. What she wants is a lacey white dress and pigtails and for me to say “Oh, yes, Mother dear.”

What she wants is for me to skip.

Most times I try. We keep our fights between us. In front of other people, I want her to be proud of me. I love my mother. I want to prove I haven’t been a complete waste.

With Dick and Stella, though, there’s a problem. Dick is nasty. He’s also a drunk. He beats Stella. I do not know how often or how bad, but she is always nervous and he is always rough, and everyone in the family knows this and no one says much about it.

“You know how men are,” the aunts say.

“They have a lot of passion between them,” the aunts say.

“Dick has an artistic temperament,” the aunts say, that word again, temperament.

I think Dick’s name suits him. I tell my mother this.

“You will be respectful,” my mother said before Dick and Stella arrived. “They’re family,” she said, as if that explained anything.

By artistic, the aunts mean Dick is a musician, a barroom pianist, and a good one. When he plays, Stella sings along, like the terrified little lab mouse she is.

Dick is not trained, like me. He reminds me of this each time we see each other.

Trained pianists, Dick says, are like trained monkeys. Real musicians don’t have to be taught how to run a scale or play the blues any more than real monkeys have to be taught to swing from trees and fling shit.

“You’re either born with it or you’re not. Me, I never had one goddamn lesson,” he says now as he settles into my mother’s good wing-backed chair.

He’s wearing Hawaiian shorts and a tank top, black socks and sandals even though it’s October, even though there’s frost coming. He has a can of Iron City in one hand. The other hand keeps time to some music only he can hear.

I think Dick is like a dog in this way. He’s always hearing things.

He taps out those rhythms on the arm of the chair. He rolls the beat through his fingers, like they’re already on the keyboard, like they never can rest. I watch his fingers, how thick they are, how big and hard his hands seem.

I imagine him hitting poor Stella, those fingers coming down again and again in a slap. I can’t imagine what she’d do that would make him so mad.

“My sweet Dick,” she says, and her voice warbles and clicks, like a cotton candy machine filled with pennies. “He plays like an angel.”

Maybe it’s something awful and simple.

Dick the angel-playing pianist can’t bear the sound of his wife’s voice.

“I’m a natural,” he’s saying. “I play by ear. Have since I was this high,” Dick says, and he takes his rhythm hand down low, an inch above the carpet, to show he’s been playing since he was a fetus.

Stella’s tweaking, a Pekinese on the Fourth of July. When Dick tells her to get up to the piano, when he tells her to sing along to what I am about to play, she jumps like an M-80 just went off in her shoe.

Poor Stella with the horrible voice sings when Dick says sing, even if he’ll slap her for it later.

I play my best for my mother, who wants to be proud, who wants to show me off, her well-trained and talented daughter. My mother sings along with Stella. They smile at each other as they sing. They hold hands, like singers do in those movies they watch.

The two of them could torture dictators into giving up their countries, their families, their stashes of fine cigars, their own ears, they’re so beautifully unimaginably off-key.

When it’s over, Dick just sits in his chair.

“Well aren’t you two the bee’s knees,” he says to my mother and Stella. He doesn’t smile. His fingers thrum their invisible keys. He’s quiet, then he says to me, “I can see you’ve practiced that one a lot.”

I nod and think for a minute he’s going to praise me.

He says, “You’ve been taking lessons for how long— three, four years now?”

He says, “How about I give it a go?”

He hoists himself out of the chair and walks to the piano like a linebacker. He sits down on the bench and it creaks under his weight. He rolls one wrist to loosen it, then the other.

Then he plays.

I’d like to say he’s terrible. I’d like to say he hits the keys with a jazzy rendition of chopsticks. I’d like to say he thumps the keys like the brute he is.

But he plays beautifully. His fingers don’t even seem to touch the keys. His whole body becomes part of the instrument, the music. There’s no separating it.

Dick is a beautiful pianist and the world is worse because of it.

“There,” he says when he is finished. “That’s how a piano’s meant to be played.”

Weeks later, I’ll get a letter from Dick, who will tell me I have the technical skill to be a concert pianist but not the heart. I have the physical ability but not the soul. I should give up and not waste any more time.

“I figure I should tell you now for your own good,” he says. “You are not a born pianist.”

It’s a crushing thing.

“You’ll thank me,” Dick writes.

•••

I didn’t thank him that day. I didn’t thank him ever. I wished him dead more than once. I wished Stella would kill him in his sleep—a pillow to the face, a stove left on, something easy like that.

Still, Dick was right. I wouldn’t become a pianist, though all these years later I still play, and one day I find myself sitting in the basement of my childhood home, playing the piano Dick once played, the very same piano, for a man who is my brother.

“You’re really good,” my brother says. “Just like my old man.”

Maybe I wasn’t born a pianist.

Maybe nobody’s born anything, though Dick thought he was.

“I know a lot of dicks,” my brother will say. “My father was one most of the time.”

I won’t know if my brother’s father is my birthfather.

I won’t be sure if it matters or not.

“Do you know any Bruce?” my brother will ask, and he’ll mean Springsteen.

•••

LORI JAKIELA is the author of the memoirs Belief Is Its Own Kind of Truth, Maybe; The Bridge to Take When Things Get Serious; and Miss New York Has Everything, as well as a poetry collection—Spot the Terrorist! (Turning Point, 2012). She teaches in the writing programs at Pitt-Greensburg and Chatham University, and co-directs the summer writing festival at Chautauqua Institution. She lives outside of Pittsburgh with her husband, the writer Dave Newman, and their children. For more, visit lorijakiela.net.

Follow

Follow