By Sara Bir

Of course I know better, but after sitting in the car for five minutes, I hit the horn. We’re ready. The pies I got up at six that morning to bake are ready. Frances’s change of clothing for the night is ready. Even the dog is ready, sitting expectantly in his crate in the back of our station wagon.

“Where’s Daddy?” Frances asks from her car seat.

“Daddy’s coming,” I say, which is true, he is. Eventually. Getting myself anywhere on time is challenging enough; getting our whole family anywhere on time is a triumph, and I almost pulled it off, at the cost of great anxiety and strategizing.

And now he’s ruining it. He’s in there brushing lint off his sweater or giving the sink one last wipe with the sponge or re-checking to see if we turned the heat off.

So I honk the horn, and it’s not a cute little hey there, the light is green! tap. It’s a get a move on already, asshole blare. Joe finally emerges from the house thirty seconds later, shaking his head, his mood as foul as mine. We will, once again, be late.

•••

I have ADD. My husband has OCD, and our daughter has ADHD. The difference between what she has and what I have is the H. It stands for “hyperactivity.” I’m excitable, but I’m not hyperactive. Some goes for our dog, who’s half border collie and half Jack Russell terrier. If you know about dog breeds, you understand that Scooter is a furry summary of our family dynamics. The collective metabolism of our household is off the charts.

Of course we didn’t get a dopey, mellow lab. Of course our dog is a mix of the two most intense, high-strung breeds. Of course Scooter sheds his silky-soft white coat prodigiously, and my husband descends upon those million stray hairs with a sense of purpose only matched by Scooter’s determination to attack the vacuum cleaner. Joe vacuums a lot, sometimes when the carpet marks from my previous vacuuming are still fresh. Many Scooter bites scar the vacuum’s plastic exterior.

An OCD-ADD union is the bleach and ammonia of marriages. We were in our twenties—what can I say? Existing was easy back then, and the pleasurable things that pushed our ugly acronyms into the margins of our consciousnesses were readily accessible. The list of what makes us compatible is long, delicious. And, on the other side of the column, there are those harsh capital letters, scrawled in black permanent marker. The delicate balance between the columns teeters, at best. We aim for teetering.

•••

For years, when I talked about my ADD, I described it as “the girl kind, where you’re dreamy and spacey.” But I stopped talking about it, because saying, “I have ADD” is like saying, “I have lungs” or “I often eat a few more potato chips than I originally set out to eat.” These things are fairly universal. Who doesn’t have ADD? So I concluded that its frequency neutered its power. All of the goals that I failed to achieve had nothing to do with that pesky nuisance. Obviously, I failed because I sucked.

Even the things I liked in school—English, art—I had to do my own way, or they didn’t get done. Filling out my math workbook in first grade, I always drew a Smurf next to each problem. The Smurfs would be polishing the subtraction figures or writing the answer in under the horizontal equals bar. Every Smurf had to be distinct. This, to me, was clearly the most important aspect of our math assignment.

Another boy in my class had ADD, but the kind with the H. His name was Ben. When seated, he created facsimiles of Transformers by sloppily cutting and folding pulpy blue- and red-lined writing tablet paper. Many of the things we covered in class are now a blur, but I clearly remember our teachers’ frustrations with Ben, the minutes dedicated during lessons asking him to stay in his seat, telling him to raise his hand before speaking. Every morning Ben’s mother sealed one of his pills in a white envelope, decorated the outside with a Snoopy sticker, and tucked it in his lunch box. One day, when our class organized our desks, about a dozen unopened envelopes tumbled from the chaos of crumpled worksheets and paper Transformers in Ben’s desk.

I didn’t have white envelopes with Snoopy stickers. My teachers expressed their concern to my mother during parent-teacher conferences, and sometimes in painfully earnest heart-to-heart talks with me. These talks invariably included the phrases “not meeting potential” and “so very smart.” This was back in the 1980s, before the rise of individualized education programs for kids with tricky learning needs. The adults in my life tried their best to reach out to me with the one tool they had: their hearts. It was not enough.

It wasn’t until high school, when it became impossible for me to coast by academically, that my mother got me diagnosed. We drove to a specialist about an hour away. He asked me to write out the alphabet in cursive and in printing, and then repeat a series of numbers after him. “Do you ever reach out and grab something without thinking about it?” he asked, and I gave him a frigid teenage fuck you look. What did he think I was, a toddler?

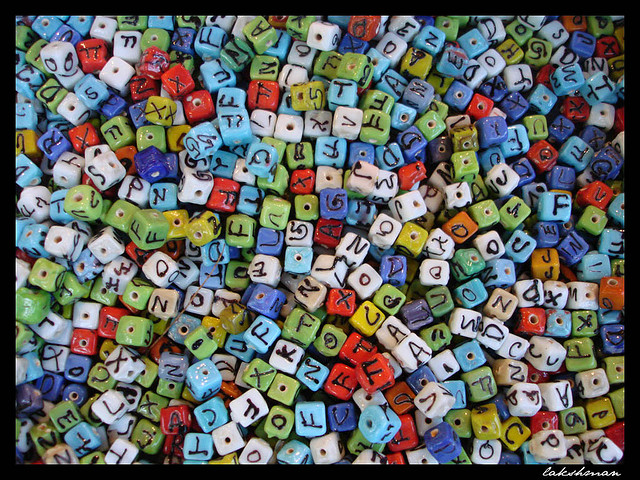

After the appointment, my mother took me to the bead store, a safe zone. I often stayed up late into the night making my own intricate clay beads in those days. It’s too bad the SAT didn’t have a bead-making section.

We did no follow-up. I didn’t want to take drugs; I was afraid they’d irrevocably change something fundamental about me, like a lobotomy.

There was no talk from anyone—my teachers, my parents, that worthless excuse of a specialist—about modifying my study habits, or about creating study habits, period. I dropped out of college, twice. I quit my first desk job—staff writer at an alt-weekly, a coveted gig for a twenty-something with no college degree—after a year and a half. ADD people do not handle deadlines well. They take on disproportionately epic importance until the scope of the deadline eclipses the project itself.

Another thing I did was work at libraries. Four of them, over the years. This I excelled at. I spent the majority of my time shelving books. There was no question about where things went. The alphabet is always the alphabet; the Dewey Decimal System is always the Dewey Decimal System. Pick up a book, look it its spine label, slide it between two other books in its appropriate place on the shelf.

At home, piles upon piles of sadly abandoned projects littered my office. The unfinished novel, the stalled book proposal, the unsent query letter. I had no idea where to begin making sense of it all. There it was, the demon phrase: “Not meeting her potential.”

Pick up a book, look at its spine, slide it on the shelf. Numbers and letters. The alphabet. P-Q-R. J-K-L. I can say it backwards in a heartbeat. It was my religion, the rosary I fingered for strength.

Five years ago, I got a prescription for generic Ritalin, hoping it to usher in a sunny new era of productivity. It’s helpful to some, but, alas, not to me. I still have the very same bottle, with maybe a dozen pills left. One day I decided to give them another chance, and I took two instead of one. The resulting freak-out was like a tweaker’s version of a bad acid trip. I drew a skull and crossbones on the bottle and hid it in the very back of the medicine cabinet. Back to the drawing board.

•••

Frances is not diagnosed, not officially. But when I see her do things, I see me. Her brain works faster than her body does. She hits, she grabs, she utters hurtful phrases. Her latest is “poopy mama.” This is when I tell her she can’t do something or have something. She wants everything all of the time, and she does everything all of the time.

This is very ADD. It’s one of the things I like about it, and it’s why Attention Deficit Disorder is poorly named. Actually, we have a surfeit of attention. The world is so full of awesome ideas! They surge through your brain like electric joyrods! Every morning, you wake up and taste the magical possibilities of the day! A hundred of them! And which one to pick? And how can all of those magical possibilities be realized in twenty-four measly hours, because they absolutely cannot wait? And oh shit, the day is already half over, because managing those electric joyrods takes an incredible amount of energy, and it turns out you will bring none of those possibilities to fruition before the sun sets. Depression sets in. Time to go home. The day is a wash. (Difficulty prioritizing. Having totally unrealistic expectations. Not handling failure well.)

Frances isn’t there yet. Her days are filled with free play and a fairly flexible structure. She usually enjoys preschool and has only had one biting incident. The school follows what is called “The Creative Curriculum.” It’s child-led, a good fit for her. My inimitable girl is a square peg. You can count on an ADD person to run black or white. We love things or hate them; we are enthusiastic or despondent; we bellow or sit silently. The world at large requires a lot of functionality in the sloggy grey middle. When we try to hit those notes, we’re out of tune. I fear that once she heads off to the round-hole obligations of standardized tests and lots of sitting still, we may be screwed.

Until then, I spy on her when I arrive to pick her up. I file away her loud voice and her bossiness and her quickness to respond to a classmate with anger. I file away her laser-like focus when she sits on a cushion by herself in the reading area, surrounded by willy-nilly stacks of books. I file away the ten minutes of cajoling and reminding it can take to get her to do something simple, like hang up her jacket or put away blocks. In the morning, when she gets dressed, she will have one leg in one underwear hole, see a My Little Pony on the floor, and then grab it and play for fifteen minutes, half-naked, half-underweared. The agenda she follows is hers and hers only. Just like her poopy mama.

•••

I have the advantage of insight with Frances. Joe does not. And we, mother and daughter, are so immersed in the rapid flow of thoughts coursing through our own brains that we can’t be bothered to consider the military dictatorship occupying his. But our domesticity has idyllic periods. We take walks together, we read picture books, we giggle at family jokes. We sit down to a home-cooked meal every night.

And that’s usually where it falls apart. Frances is the wildest eater in the four-year-old kingdom. She can render a peanut butter sandwich into a three-foot radius of crumbs and greasy fingerprints in about thirty seconds. And she never just sits at the table; she squirms, flops, slides out of her chair, a dynamic smear of motion. Joe’s watchful eyes zoom in as if a massacre were in progress. “Frances!” he’ll chide. “Don’t do that!” Then, to me: “Can’t you see the mess she’s making? Why aren’t you stopping her?”

I don’t stop her because I’m totally engrossed in the cookbook that I brought out to occupy myself while waiting for Joe to come to his perfectly executed meal. “Risotto waits for no one,” the Italians say. I have no idea what on earth Joe does in those lost minutes it takes him to get his ass to the dining room, where his plate of pasta or curry or—god forbid—risotto sits impatiently, its freshness plummeting. I know what Frances does, though. She digs in without him. For a while I made her wait, but no longer. Why should she? She got to the table on time, and Frances showing up anywhere when she’s asked to is a giant deal.

After dinner, we clean up. I try to do most of it, because if Joe takes on the clean-up, he’s sucked into a black hole of feverish wiping and sweeping and wiping. The kitchen sink is his trigger area. He’ll walk by and grab the sponge and dab at a non-existent drop of water, and then do it again, and then again.

“I already got that,” I’ll say.

“There’s still stuff here, I can see it,” he’ll say.

“Just put down the sponge and do something else,” I say. “I told you, I already got it.” This is an affront to me, to the miracle of me being tidy and conscientious instead of sloppy and careless. It is an affront to me swimming with all my might against the mighty current of my own nature.

And he goes on, wipe wipe. Dab dab. Oh, the sex we have not had because of a fucking sponge.

I do not shelve the cookbook.

•••

Joe has pretty awesome ways of coping. He makes colorful art using exactingly spaced rays of narrow drafting tape. Patterns. Repeating. He plays the drums. Patterns. Repeating. Like me, he eschews drugs. He says the ones he’s taken, Paxil and something else, made him feel at a creepy removal from everything going on around him. Joe’s OCD isn’t just with physical actions. It’s about thoughts, repeating. It’s dark in ways that I can’t penetrate. He grabs his skateboard and grinds his favorite manual curb over and over again. That’s on the weekend. On weekdays, there’s always the sponge and the counter.

At home, our alphabet is in ribbons. There’s no A-B-C-D, like my divine library days. It’s got extra letters in some spots, and it’s missing other ones entirely, and it’s not even in the right order. It goes ADD-OCD-ADHD.

You might have your own alphabet, too. It could go OMG-MS or PTSD-FUBAR. Your hard alphabet is its own unique code, like DNA, even if its letters happen to match my hard alphabet exactly.

You can go looking for people to cut you slack, and maybe they will, a little, but the alphabet will still be there. You can tell yourself that you’ll triumph over it, but you’ll be wrong. A hard alphabet has no eraser. The only thing you can do is cope. All the people telling me to not eat gluten, or that Ritalin will fix me, or that my disorder is totally imagined? Go answer that knock at your door. I sent you a present. It’s an otherwise sane man with a vacuum and his cute little dog. They’ll be spending the night. Have fun.

Sometimes I meet people and spot the ADD in them. It’s like Gaydar or Jewdar. Hmm, I think. Does she? I find myself wanting to embrace that person, tell her I get it, that I’m part of her tribe. But my non-ADD self prevails; I buckle down that thought and keep it from wiggling out of my mouth. Just knowing it’s real is enough to keep me going. I grab the hand of the invisible, impulsive companion in my brain and look it in the face. We have to walk through life together, grapple for some kind of sync. We will cut the OCD and the ADD some slack. We will not honk the horn. We will have an awesome Thanksgiving, Scooter and pies and everything, even if we are half an hour late. And we will own our hard alphabet, backwards and forwards.

•••

SARA BIR meets professional deadlines and is occasionally late for personal appointments. Her writing has appeared in Saveur, The Oregoninan, The North Bay Bohemian, and on The Huffington Post; she’s a regular contributor to Full Grown People. A graduate of The Culinary Institute of America, Sara writes about food and develops recipes in her southeast Ohio home. Her website is www.sausagetarian.com.

Follow

Follow