By Ellen S. Wilson

The smell hits the moment you walk through the back door into the kitchen—damp wood, mildew, and sadness. In just a few minutes, it is possible to acclimate to all three.

My sisters and I have come with my mother to The Mountain House, a sturdy little family vacation home in western North Carolina, built up on a ridge that is said to be haunted by the ghost of Mrs. Heaton. We’re here, as my mother says more than once, to “tear the house apart.”

But first, the ghost story: This ridge was the property of the Heatons years ago, and greatly beloved by Mrs. Heaton. When financial hardship hit, Mr. Heaton, less emotionally wrapped up in the land, wanted to sell. Mrs. Heaton, whose name may or may not have been Loesa Emmalie, resisted. The years went by, the times got tougher, and one day Mr. Heaton made a sneaky trip into town and sold the land without telling his wife. He didn’t have to—by the time he got home, she had hanged herself from a tree, and an enormous white owl sat in the branches above her nodding head, screaming “like a woman,” the storytellers always say.

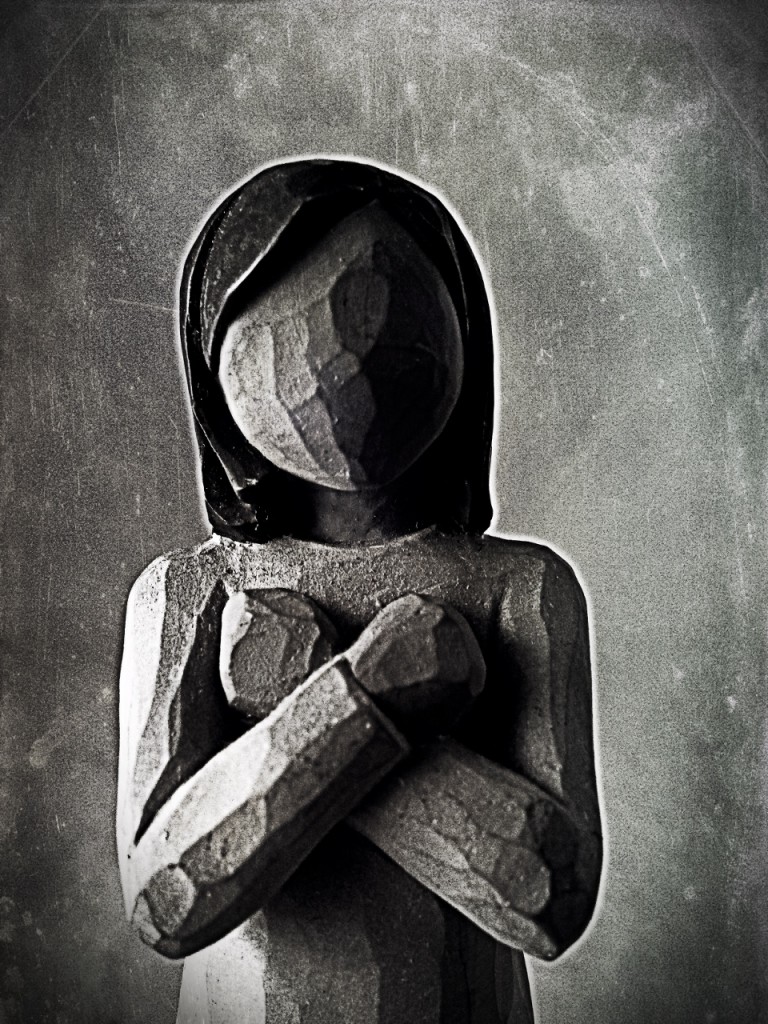

To placate the ghost of Mrs. Heaton, whose white owl still screams in the night, or perhaps to honor her memory, the inhabitants of the vacation homes that now dot the hillside have representations of owls on their placemats, hand towels, coffee mugs, everywhere. My own mother collected hundreds of tiny owls, and we all abetted her habit because a souvenir owl was a small and convenient gift for her when we traveled or hunted for stocking stuffers. An owl for Mom, from Turkey or Kenya or Lake Tahoe. Bookshelves laden with owls made of stone, glass, crystal, and porcelain are partly why we have come. It’s time, we have decided, to save anything we care about from the encroaching damp. We are rescuing our treasures from the future. If we have learned anything from the mountains, it is that appearances to the contrary, not even they are eternal. We are here to make one last stand against that reality.

The owls belong to my mother, but the ghost of my father sits in every corner of this house, in the barn wood paneling, fine rugs, bird prints, and odd collectibles. We lost him once already, seven years ago, and we dread losing him again to creeping mildew and anonymity.

•••

I’ve been coming to these mountains and tolerating the stomach-churning hopelessness they inspire in me since I was two years old, long before The Mountain House was built. Every summer—every goddam summer—my parents would load my three sisters and me into the car in Louisville, Kentucky, and drive seven hours over the mountain roads while I lurched and puked in the back of the station wagon. The way, way back. This began before there were seatbelts. Once we arrived, there would be warm ginger ale to quiet my heaving guts while we settled into our cabin at the High Hampton Inn and Country Club, a worn, sprawling establishment well over a hundred years old that prizes tradition and simple virtues and has now added a spa and some llamas (llamas being indigenous to the Blue Ridge Mountains).

Our regular cabin was a wooden structure with twin beds, soft, thick linens that never felt completely dry, and a lovely veranda overlooking the lake. The place smelled of boxwood—subtle, sweet and green—and my normally spider-fearing mother loved it so much she suspended all her fears when we arrived. The mountain air reassured her. Not me.

The lake our cabin overlooked was still, small, and—to me—fathoms deep. Potential death lurked in its depths, and there was said to be a dam that you shouldn’t paddle your canoe too close to, although when I found it as an adult I realized the silty pool at its base was hardly lethal. But even now that lake, which I have swum in, and paddled over, and hiked around, can fill me with dread. The memory of my pale legs dyed green by the murky water, my vulnerable white body suspended over god knows what dark threat, and my forcing my teenaged self to dive down and swim out to a tethered float, causes an internal quake when I’m sitting on my own dry porch in Pittsburgh miles away.

During those family trips, my sisters and I were habitually shunted over to the Children’s Program, and since I’m the youngest, I was rarely with any of them. My happiest day was when I cut myself on a rusty nail in the donkey barn and one of my sisters had to rescue me and take me to my mother, once she had finished on the golf course and was available to tend to my wound, and perhaps to worry about me a little. My unhappiest day was the evening hayride (this happened frequently, this unhappiest day) in a wagon filled with prickly bales and noisy children, pulled by a mean woman on a tractor. I remember ghost stories I took very seriously, and kids only a little older than me singing songs I didn’t know. I remember feeling powerless, and suffering the necessity to either pee in the woods or wet my pants, and not knowing which was worse.

There was no reason to have been so miserable. My mother and father were loving and attentive enough. I know now that parenthood means a gentle pushing away, and that the only time one can encourage dependence is during the first months of breastfeeding. Apart from that, it’s all “you can walk across the room unaided, you can survive a morning at preschool without me, you can sleep at a friend’s house, go to college, go to France.” But what did I know, at age four? The mountains made me then, and make me now, feel irresistibly lonely, pressing-on-a-sore-muscle lonely.

Somehow the eternal mountains embodied impermanence and loss. My oldest sister, the one who was my surrogate mother much of the time, was found sleepwalking toward the lake one night when she was fourteen, and the story was presented as a near tragedy. My father caught her just in time, before her pale foot was sucked into the black greeny goop and she was lost to me forever, becoming the next ghost story. The image of her small figure in a white nightie (she would have needed one, if she was to haunt the lakeside), foot extended from the slippery rocks along the shore, rocks alive with snakes and toads, entered our own family lore, those unsettling tales on which the mountains depended to keep you from feeling too comfortable as you sat in a rocker and digested a doughy mountain dinner. The lake was peaceful and silent, we swam in a little fenced off part during the hot humid afternoons, but the grabby mud bottom was never trustworthy.

•••

The summer I was nineteen, my father got me a waitress job at the resort. I don’t remember being given an option about that. The owners couldn’t say no to him, either—he’d been a patron there for years, had bought that piece of property on the ridge they owned that overlooked the resort, and was building himself a house. And perhaps most important, my father was one of those charming, friendly people that strangers took to on first sight and never had reason to change their minds. When he was dying, the mail carrier came in to say goodbye. His funeral was standing room only. Naturally, the president of High Hampton Inn agreed that I could wait tables in the creaking sunlit dining room.

I felt the old lurch of nausea and loss as my father drove away at the beginning of that summer. His natural optimism (along with his desire for me to stop being such a lost puppy) convinced him that I would manage. He had been mostly abandoned by his own father at age five and sent off to live with relatives to save money, and he turned out just fine. He knew I would meet this minor challenge and I did, befriending another summer hire and convincing her to let me share the trailer she had rented—housing was not included in our stingy wages.

And there I was, stuck in a place of fear and loathing, zipped into a gold polyester dress and ferrying glasses of iced tea to guests in my section. It was an easy job, and I managed to pay my rent in tips and send my paycheck home to my sister in Louisville, who put it in the bank for me. By August, I had more than enough to buy the electric typewriter on which I would write my senior thesis in college.

In the meantime, my trailer-mate and I sat on our tiny porch, listened to the radio because there was little else to do, smoked (or I did, again because there was little else to do), and necked (or I did, see above) with the boys across the driveway who were also there for the summer. When we got off work, we grabbed sleeping bags and ran up the various mountains to spend the night, no tents, no food, no supplies. We went into work the next morning needing a shower and a good nap and convinced that we were living much more intensely than the middle-aged people waiting for me to pour their coffee. Being middle-aged myself now, I know that that was true.

•••

My parents came to spend their customary week in the mountains that summer and check on the construction of their new house, and one day during the long afternoon break, I saw my father sitting on the lawn in a shaded Adirondack chair. I invited him to go with me to, as I put it, “see something pretty,” and luckily for us both, he accepted. I drove him to my favorite waterfall, a big one that rushed thirty or forty feet over a cliff, reachable by an easy path from a rough parking lot. Above those falls, I had camped and swam and slid into the pools in a game that terrified the older waitresses at the resort, who knew of people swept to their deaths doing that. I had slept on the flat rocks at the very top, rocks that were surely submerged when the water was high. The waterfall was mine, and I wanted to share it with my father.

This outing led to further discoveries as my parents began to find more in their summer vacation than golf and cocktails. The new house acquired some new dimensions, and the family a veneer of rustication. We hiked in the mountains and provided our own names for favorite spots (Toe-Mash Creek was one). We picked thumb-sized blackberries from the brambles down the hill from the house and made jam and pie. My father bought a small used pickup truck.

High Hampton Inn had its charms, with the grease from its famous fried chicken embedded in the pine walls along with the odor of loneliness, but the mountains themselves acquired characters wholly separate—blooming, gray, and fearsome. People do die there—my own father slipped on moss once, reached for my hand, said later that I had saved him from a fatal fall. I did not remember it that way, but that didn’t help. To love the mountains the way Mrs. Heaton did is to wordlessly accept the inevitability of loss, all kinds of loss.

Years passed. One summer, the wild blackberry brambles were mowed to the ground and never grew back. If we had known they were a temporary pleasure, they would have become too precious and we would have enjoyed them less.

The rough parking lot at my waterfall was paved and a map installed, and I felt it like abandonment, like my old secret lover was openly dating other people. Trails were marked clearly, construction and condos were everywhere, and the hidden pools and perfect little glens were all discovered. Now when you hiked in a place that felt deserted, you came across used tissue and empty Perrier bottles. The town of Cashiers that provided High Hampton with a mailing address grew from a minimal crossroads to a town center with shops devoted to baskets (just baskets) and delis, and cuteness. There was more to offer a nineteen year old—artisanal coffee, for example—but none of it felt relevant anymore.

•••

My family’s own history unfolded at the Mountain House. It wasn’t any messier than most, just the run-of-the-mill ending of marriages, illness, disappointment. And into this soup of memory and history we have come, to tear it all to pieces in a hopeless attempt to rescue the parts we want to save. The Audubon print has mildew behind the glass – it needs to be taken to dryer quarters and re-matted. Is there any way to remove the spots on the silk hanging from China? The big rug in the living room smells musty. Something must be done. So we go round robin in a civil exercise to say what we really want, what we can’t live without, and we try to be generous. “I gave Mother and Daddy that, but I’m so glad you want it.” Of course the thing we want—do we?—is to undo some of that passage of time, to go back to the miseries of childhood, to put the past in a box as though that meant not losing it.

I took my own children when they were small to see the donkeys and feed them carrots and crackers, and if my urban kids recognized the sadness in the donkeys’ faces, they did not let me know. There was no need for a salutary cut on a rusty nail for them—I was right there, and rightly or wrongly I had no plan to send them on any hayrides. They have their own vulnerabilities, their own dark lakes that are not to be found at High Hampton.

At the end of the weekend, I say goodbye to my oldest sister, and tell her I love her, and she looks at me questioningly and I know that we have not said everything there is to say and that we never can. If we sit in a circle in the living room now stripped of the colorful rug and travel mementos, the walls bare of pictures, and we acknowledge what we have done, we will be devastated. We can’t turn and look the sadness in its face, we can’t tell my mother it’s all over, which at ninety-one, she understands well enough. Here in the stoic, silent mountains, it is better not to say.

•••

ELLEN S. WILSON lives and writes in Pittsburgh, PA. Her work has appeared in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Carnegie Magazine, and other local and national publications. She is proud to have her first essay in Full Grown People.

Follow

Follow