By Lisa Lance

Shivering in the crisp December air outside Papà Giovanni, a restaurant on the corner of Via dei Sediari and Via del Teatro Valle in Rome, my husband, Chris, and I wait for the sliding glass door to open. We see couples inside, nestled in red leather banquettes and wooden chairs at two of the half-dozen close-set tables. Red and white tablecloths set off vintage china, and glittery poinsettia decorations remind me that it is just a few days after Christmas, even as fresh tulips in the center of each table hint at the coming spring. Dusty wine bottles line the room, tucked into alcoves or perched on ledges. An eclectic mix of drawings and paintings, along with faded postcards of Sicily, clutter the brick walls.

It is just as we remembered.

We are in Rome to celebrate our tenth year of marriage and also to escape a stressful year at home. Our relationship is strained by a multitude of factors: family drama due to the messy divorce of my husband’s parents, which has taken a broader emotional toll than we expected; Chris’s demanding job, which keeps him out of town for weeks at a time; and my perpetually tired and frazzled state due to graduate school, with two classes each semester on top of a full-time job. We need a break, and I hope our holiday to Rome will be a bright spot in the brewing storm—if not a full repair, then at least a period of some romance, a reminder of what it was like when we were happy.

After we are seated at one of the small tables, the waitress brings us aperitifs of warm spiced wine in small china cups on saucers, and the chill of the evening retreats as I sip. She hands us menus, blue for “the gentleman” and pink for “the lady”: the blue version includes prices for each item, while the pink version lists calories. If this were a restaurant at home in the United States, I would be offended, but here it seems charming.

The wine list is a worn tome that resembles a guest book from a wedding. As Chris turns the pages, I notice the list of wines written by hand, some entries scratched out or modified, others smudged by water stains. I laugh at the small size because, in my memory, the wine list has taken on mythical proportions. As I recall from the first time I saw it, the book had been the size of a dictionary and had been wheeled out on a cart, attracting stares from the other customers.

•••

Our first trip to Rome ten years ago was my initiation into the world of international travel, and all of my memories shine with the luster of this perspective, fresh and new. We had an extravagant five-course dinner and then wandered the cobblestone streets to the nearby Piazza della Rotonda, where people milled around one of Rome’s most impressive monuments, the Pantheon. Sixteen towering Corinthian columns support a triangular pediment inscribed with the stamp of Marcus Agrippa: M. AGRIPPA.L.F.COSTERTIUM.FECIT. The domed roof is larger than that of the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, D.C., and, at 142 feet in diameter, nearly the length of an Olympic-size swimming pool. In the center is a large oculus from which red rose petals rain down on Pentecost.

The interior of the Pantheon was closed that evening, but we passed the obelisk-topped fountain that pierces the sky like an upturned sword, water babbling from the mouths of the marble masks at its base, and climbed the steps of the monument anyway. We stood among the columns of the portico, and Chris suddenly dropped to one knee.

“What are you doing? Get up,” I said. I thought he’d had too much wine at dinner, and I pulled his arm, trying to get him to stand.

“Oh, no,” he said as he reached into his pocket. “I’ve been planning this.” He pulled out a gold band accented with a row of seven small diamonds and held it up to me.

“Really?” I was floored. We had moved in together after dating for only a few months, but in the past year of our shared life we hadn’t discussed marriage. Our relationship was comfortable and fun, and I had assumed it would be at least five years before we took the next step.

“Well?” He was still on one knee.

“Really?” I still didn’t quite believe it. “Really?”

His brow, framing earnest, clear blue eyes, started to crease with worry. “Will you say yes already?”

“Yes!” He put the ring on my finger, and we kissed. The streetlights around us seemed to brighten, and the other people in the piazza faded away.

An enterprising street vendor approached us, and Chris purchased an armful of red roses and presented them to me. As we walked back to the hotel, the outlines of buildings seemed fully in focus; everything was crisp and clear. We passed the Monumento Nazionale a Vittorio Emanuele II in Piazza Venezia, and its marble walls and columns glowed bright white against the night sky, the twin statues of the winged goddess Victoria and her chariot soared, it seemed, in celebration high above us on the roof of the monument.

•••

Back in 2002, we were still going through the transition from college student to adult. We’d had internships and temp jobs, but hadn’t yet started our “real” careers. We had academic knowledge but little actual experience; we were fairly broke but full of optimism. Our tastes then had only recently shifted from Boone’s Farm and Miller Lite to Tanqueray or Chateau Ste. Michelle. Now, after years of wine tastings, we can tell the difference between a Malbec from Argentina and a Cabernet from California, and on our return visit to Papà Giovanni, my husband confidently makes a selection from the list.

The wine decanted, we look again at the menus as we nibble on focaccia with truffle butter and reminisce about our last visit. “What did we even order?” I say.

Chris recalls some kind of eggplant stack, slices of the vegetable layered with tomato sauce and cheese and balanced on a plate like a small, square Tower of Pisa. I’d had veal for the first and only time in my life, a choice that had seemed so elegant then, but after eight years as a vegetarian would be unthinkable to me now. We had tried to order five courses and share them, but we were unable to convey our wish to the waiter and ended up with two of each dish. It was the biggest and most expensive meal we have ever had in a restaurant.

This time around, we order separately, and only one course at a time. I begin with a salad of arugula, pears, walnuts, and parmesan—a medley of sweet and salty, soft and crunch. The server returns to take our orders for the main course, and I select Cacio e Pepe, a traditional Roman dish of spaghetti with black pepper and parmesan. The strength of the dish lies in its simplicity. The noodles are al dente, and the sharp cheese and spicy pepper flavors mingle and dance on my tongue. For dessert, a decadent chestnut soufflé is perfect with a cup of Italian espresso, strong and smooth enough to clear a path through the gastronomic haze that begins to cloud my mind.

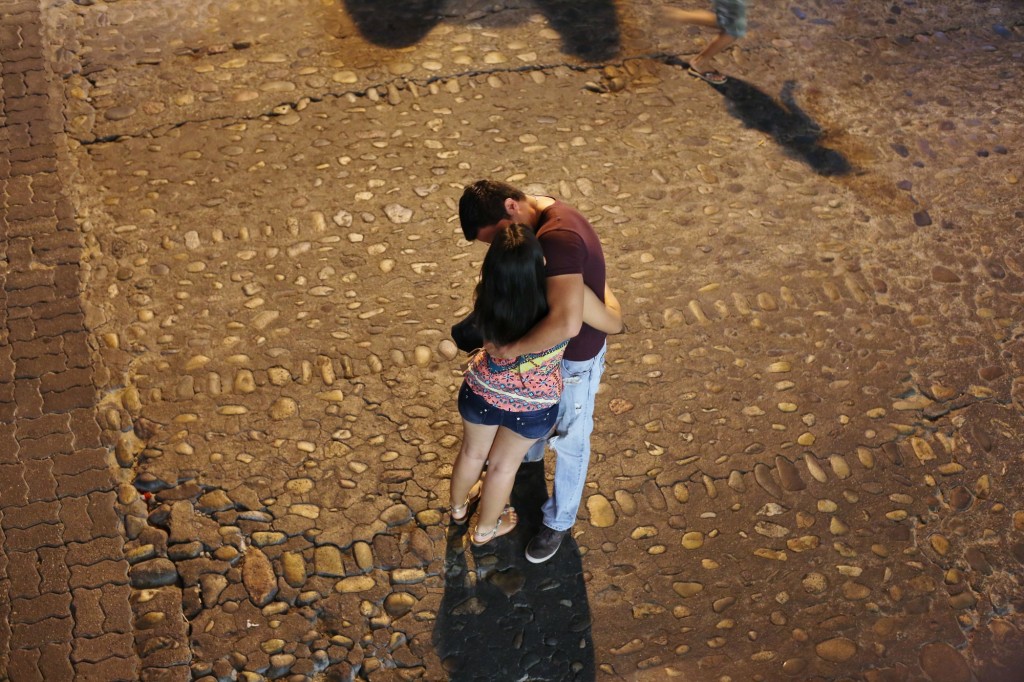

After dinner, we wander the cobblestone streets. Strings of lights twinkle overhead, criss-crossing between the buildings like spider webs weighted with shimmering drops of dew. I catch faint whiffs of cigarette smoke as we amble along. Italian couples walk arm in arm, parents navigate strollers over the uneven pavement, and Asian tourists pause to take photos. Unlike cities at home, nobody here seems to be in a hurry. As we exit the narrow alley, the Pantheon, bathed in golden light against the dark night sky, rises before us.

The enormous bronze doors are open. “Do you want to go in?” Chris asks.

“Yes.” Entry is free, so we join the flowing crowd to explore the space together. The interior of the temple is harmoniously symmetrical—the distance from the floor to the top of the dome is equal to the dome’s diameter. The floor and walls are inlaid with marble, rectangular patterns of muted gold, maroon, and blue interspersed with swirling veins of grey and white.

As we wander through the vast interior, I am suddenly hungry to learn everything I can about this building that has such a prominent place in my memory, and I stop to read every information plaque available. Built by Marcus Agrippa around 25 B.C., the temple was originally a place to worship Roman gods, but, like so many historical places in Rome, it was later converted to a Christian church. Alcoves along the rounded wall hold statues and murals—some of Christian significance and some depicting more ancient figures. The more I learn, the more appreciation I have for the detailed architecture, the majestic beauty, and the fascinating (if not always pleasant) history of the temple. Grand tombs hold the remains of Vittorio Emanuele II, the first ruler of a united Italy, and Umberto I, a king in the late nineteenth century under whose orders hundreds of starving peasant protesters were killed. The famed Renaissance painter Raphael is also interred there, along with his fiancé, Maria Bibbiena, despite rumors that his early death at age thirty-seven was the result of a tryst with one of his mistresses.

How could I have missed all this on our first visit?

Chris and I have weathered our own conflicts over the past decade. We’ve dealt with jealousy and baggage from past relationships, struggled to find time for each other, moved far from everything familiar to a new city with no network of social support. We married young at twenty-four, and we’ve worked hard to create harmony in a home where our evolving personalities, interests, and worldviews are often at odds. Any discussion about politics, for example, quickly spirals downward from friendly debate to contentious argument. We’ve felt the ripple effect of marriages crumbling around us, from my step-sister and brother-in-law, who filed for divorce barely a year after their wedding, to my husband’s father and step-mother, who called it quits after more than two decades together. How long can we avoid the afflictions of infidelity, boredom, and financial distress that spur the downfall of so many other couples? Other couples who began their lives together just as we did, filled with optimism.

Even an edifice as strong as the Pantheon needs to be rebuilt from time to time. Agrippa’s original structure burned in 80 A.D. Then, after being rebuilt by Domitian, it burned again in 110 A.D. It was restored by Hadrian in 126 A.D. and could not have remained “the best-preserved building in Rome” without periodic restoration projects throughout the centuries.

That monument was an apt place to begin a marriage, and restoration is precisely the reason we returned to Italy. More than just a building, the Pantheon is solidly built, with walls that are twenty-five feet thick, and it can certainly withstand the occasional crack—even a deep one—as well as the repairs necessary to maintain its majesty. It has survived two thousand years of wars and conflicts and cultural changes. It has been home to dueling religious and political philosophies, and it serves as a place to remember and celebrate people with complicated pasts. Yet despite its age, or maybe because of it, the temple is still a magnificent site to behold. Instead of shutting out the elements, the oculus remains open, and allows sunlight to shine and rain to fall inside its walls.

Chris’s proposal to me in Rome has become something of a legend for us, the first story we tell when others ask about our relationship, the memory we recount each year on our anniversary. It’s as much a part of our history together as the day we first met. Revisiting a place with such personal significance carries risk, and I had been worried that this trip might be a disappointment, that the rosy glow of recollection and the passage of time might have morphed the actual events into something mythical that could never be recreated, that the story now only held its romance in the retelling. My memories of the first visit are like a giant Impressionist painting, vivid, yet vague. Ten years later, I pay more attention to the details—the postcards on the walls, the dust on the bottles, the inscriptions on the tombs—than I did the first time around. Will the cathedral of our marriage weather another ten years?

The passage of time allows for physical wear, for philosophical shifts, for falls from grace, but it also allows for rebuilding. Perhaps we can learn from past mistakes … a bit like I learned to order the perfect dinner from a foreign menu. Perhaps we can learn to communicate clearly. Not to be greedy. Learn to appreciate simple flavors, and to savor each bite. I will think of this when times are difficult, as they have been lately, and I feel the way I did outside Papà Giovanni, shivering in the cold, waiting for the door to slide open and let me back into the familiar warmth inside.

Coda: As it turned out, our marriage would not weather another decade, and two years after Chris and I returned to Rome, our divorce was finalized. Restoration isn’t always possible, but while we may not always be able to depend on the strength of buildings or institutions, in their destruction we sometimes find a greater strength in ourselves.

•••

LISA LANCE is a writer living in Baltimore, Maryland. She earned an M.A. in Writing from Johns Hopkins University. She currently serves as an editor for The Baltimore Review, and her articles and essays have appeared in publications including Baltimore Magazine, National Parks Traveler, Outside In Literary & Travel Magazine, Seltzer, neutrons protons, Bmoreart, and Sauce Magazine. This is her second essay for Full Grown People. Learn more at www.lisalance.com.

Follow

Follow