By Browning Porter

My daughter Shannie is singing an old song. It goes:

Meet me in the middle of the day.

Let me hear you say everything’s okay.

Bring me southern kisses from your room.

She’s eight, though, and she has a lousy ear for pitch, so it’s all off-key, sliding around the melody like a kid in socks on a hardwood floor. Which she is also doing literally.

Meet me in the middle of the night.

Let me hear you say everything’s all right.

Let me smell the moon in your perfume.

The song is called “Romeo’s Tune,” by a guy named Steve Forbert, and it was a hit in 1980. It made it to #11 on the charts. Shannie likes it. Maybe because she’s a precocious Shakespeare fanatic, and Romeo and Juliet is her second favorite Shakespeare play, or maybe because it’s a pretty good song.

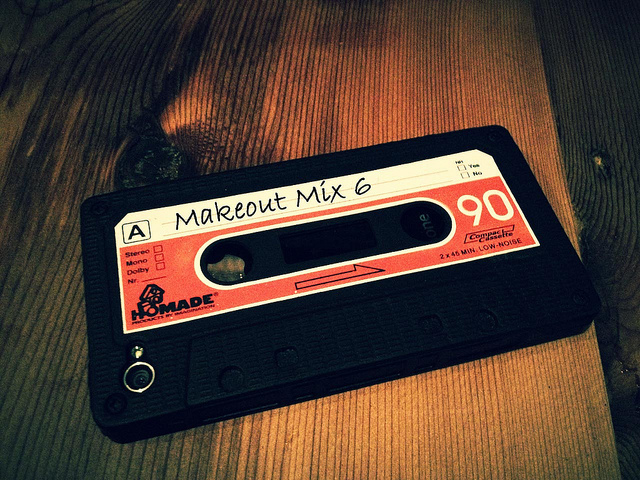

I remember when I first really became aware of this song. It was the summer after my first year in college, and my friend Phil and I were trying to score some weed. So we decided to drive two hours from DC all the way down to Charlottesville to visit my cousin Missy. Missy was a few years older than me, twenty-two or so, and she was one of my favorite cousins. She was very pretty and sweet, a kind of fun-loving hippy chick with a boyfriend who played guitar for a popular Grateful Deadish jam band, and I was pretty sure she would know where we could get some marijuana. So we went to visit Missy, and sure enough she did have a little sack of weed, which, because she was such a sweetheart, she just gave to us. But before we left, she said, “You should listen to this tape.” And she pulled out this cassette tape and put it in a boombox, and we all smoked a bowl and started listening.

This tape was a work of art. The little paper insert to the plastic case had been made by hand, a collage of old comic strips and wrapping paper, with a title drawn across the spine spelling out VARIOUS MUSICKS. The K was pretentious, or ironic, or both. It had a song list typed by an old ink-blotchy typewriter and pasted in place, and it was filled with deep cuts from Blondie and Neil Young and NRBQ and The Stranglers and “Romeo’s Tune” by Steve Forbert. I asked Missy who had made it, and she said, with a hint of embarrassment, the name of a boy. I can’t remember the name. His name meant nothing to me. But we kept listening. “Do you like it?” said Missy. “You should take it.” And I did.

I listened to VARIOUS MUSICKS with a K for years, riding in my car, or in the background on a sunny afternoon. One of the things I loved about that tape was that its creator was so clearly smitten with my cousin Missy. The whole thing was filled with longing and hope and despair. Which I understood completely. Missy was lovely. She must have had guys falling in love with her all the time. And I knew how that felt to fall in love—not with my cousin—but with girls like that, and so I couldn’t even remember this guy’s name, but I felt a kinship with him when he tried to speak to her through Steve Forbert’s “Romeo’s Tune. It was the perfect song for a mixtape. Meet me in the middle of the day. Let me hear you say everything’s okay.

I felt a little sad for him that his mix tape to Missy had missed its mark. That it had fallen into hands of some random younger boy cousin.

Oh, Gods and years will rise and fall,

And there’s always something more.

Lost in talk, I waste my time,

And it’s all been said before,

While further down behind the masquerade

The tears are there.

I don’t ask for all that much.

I just want someone to care.

Well, I was someone—not the right someone—but I did care. It was the least I could do, to appreciate how he felt, and I did, often, for many years, until the invention of the CD. All the mixtapes I made myself over the years were a little inspired by his.

•••

Years later, I was standing in line at the grocery store, and my eyes were drawn to this woman waiting in the next line over. I didn’t recognize her, and yet somehow I did. It was the strangest feeling. I was sure that I’d never seen her before, and yet I felt I’d known her all my life. I couldn’t keep myself from sneaking glances. I never believed in anything so silly as love at first sight, but there was something happening here that refused to be explained. It wasn’t that she was extraordinarily Helen of Troy beautiful or anything. I just had this feeling, like we’d known each other long ago in a dream that I could almost remember, and all I wanted to do in that moment was to meet her and make sense of this. Which was awkward. Not least of which because I was married. Maybe not blissfully married, but still. What the hell was wrong with me?

And then—BAM—suddenly I understood. I knew who she was. She was the older sister of my best friend in high school. I hadn’t seen her over a decade, long enough for me to enter some eerie, liminal state between remembrance and forgetting. It felt a lot like being in love. I don’t know, maybe those two states occupy the same region of the brain or something. But stranger still, and kind of sad and lucky given that she and I were both all grown up and married, was that as soon as I knew who she was, the sensation of being in love went away, and she went back to being a girl I once knew grown into a woman. It was like losing your footing and catching yourself, a second of being airborne and weightless and in peril, except that the peril is delicious in a way that didn’t even know you missed, and when you are safe again in the gravity of your life, you go on missing it for a bit as you carry your bags to the car.

It wasn’t as though I’d even had a crush on her in high school. I liked her well enough, but I liked all girls back then. And she was three years older than my friend and I. We were pimply little frogs, and she was a benevolent, big sister, soon off to college. I had only a handful of memories of her. One of them was that that summer we’d been at my friend’s house, and I had been playing VARIOUS MUSICKS, and she popped her head in to say hello, and she’d heard “Romeo’s Tune,” and she said, “Oh, I love this song. I always liked that line about how they fade like magazines.”

I hadn’t really noticed that line yet. And after she said that, I always noticed it. And ever since I’ve always loved that line as well.

•••

I met Steve Forbert. My band opened for him one night at the Gravity Lounge. All these years later, he was still touring, driving himself from town to town, playing tiny rooms, rooms so small that a band as obscure as mine could share the bill with him. I was kind of excited to meet him, though what could I have to say to him except that I’d always loved his song “Romeo’s Tune.”

And it occurred to me that this was probably something he’d heard so often that he must be sick of it. I would be. Think of it. He had one hit song in 1980. It made it to #11. And that was the highwater mark of his fame and fortune. I couldn’t name another song that he’s recorded in the next thirty years, and I was willing to bet that few people could, and so everyone who remembered this song would have to mention it, and he would have to graciously acknowledge their admiration for this one song, this one sentiment that he’d felt once back when he was young and pretty and ambitious.

I wrestled with this as I waited to meet him. But he never showed up for our set, and then he breezed in fast to play his own. And he was good, though not amazing, and at the end of the night he dutifully played “Romeo’s Tune,” and then the show was over and he was packing up to leave. I bought his Best Of CD, put the cash in his hand myself, because it had the one song I knew on it. I invited him to have a beer with us, and he said no thanks, and we wished him well, and he hurried for the door. Maybe I felt a little snubbed. The club owner told me later that he had hours left to travel for another gig in another state.

It’s king and queen and we must go down

Behind the chandelier,

Where I won’t have to speak my mind,

And you won’t have to hear

Shreds of news and afterthoughts

And complicated scenes.

We’ll weather down behind the light

And fade like magazines.

•••

Nowadays when people want to make mixtapes, they do it on iTunes. It’s not the meticulous labor of love that it once was, cuing up the vinyl and the tape, and punching fat, clunky buttons with twitch-fingered timing, and lettering the cases in ink until your hand cramps. Now it’s kind of easy. You drag and drop songs into a list, and you can reorder them on a whim, or if you change your mind and decide that song reveals too much or too little of what you feel, you can just delete it, and the hole fills in as if it were never there.

One day I was looking at the playlists in iTunes on our family computer, and I saw a list that I didn’t recognize, and I opened it. I could tell by reading the titles that it was mixtape. A mixtape in love. Yes, “Romeo’s Tune” was on there. Ripped from the CD that I bought from Steve Forbert the night I met him. It’s the perfect song for a mixtape. Even the mixtape that my wife was making for her lover.

Meet me in the middle of the day.

Let me hear you say everything’s okay.

Come on out beneath the shining sun.

Meet me in the middle of the night.

Let me hear you say everything’s all right.

Sneak on out beneath the stars and run.

This was not the moment that I knew, or anything so dramatic as all that. I knew already. This was just one extra little punch in the gut. Everything is not okay. Everything is not all right.

Since she moved out, there are some nights that the kids and I need cheering up, so we do something that we never used to do when we were all together. We have a little dance party in the living room. I put on the music on the family computer. I make a little mix for them. I don’t know if it’s a kind of masochism that made me put “Romeo’s Tune” in that mix. Maybe it’s that I wanted to take it back. I was not ready to let her take that song away from me and give it to a stranger. I don’t want to wait for the pain to fade like a magazine. I want to take seeing that song in that context and tape over that experience by hearing again and again and again in a new context. So I put it in the mix for me and my kids to dance to. And now my daughter loves the song, and she dances around the living room like a hippy chick, singing “Romeo’s Tune,” all out of tune, sliding, and holding on.

•••

BROWNING PORTER has been in two musicals, both times in the chorus, first as a singing pirate, and then as a singing Nazi. He started smoking cigarettes when he was a singing Nazi. It took him twenty years to quit.

Follow

Follow