By Kathleen Guthrie Woods

I’d recently moved in with my soon-to-be-husband when—“Hello, he-loo-oh!”—the lady from across the street hustled over to introduce herself.

“You look just like your sister!” she gushed.

“Uh, I think you have me confused with someone else.”

“Oh, no. You look just like her. Your sister!”

Actually, I don’t. My little sister stands a good four inches over me and got all the dark genes, while I got the “Irish” ones.

But my new neighbor insisted. “You know, I saw her, when she lived here. And then you came!”

Oh, sweet god, not again. For it wasn’t my sister she was comparing me to. It was my husband’s first wife. His beloved first wife. The one who died.

I’ve known from the start that my husband had a type: blonde hair, blue eyes, fair skin—what he calls “pasty.” But she was petite and I am tall. She was left-brained and I live in the right. “You’re funny,” my husband said when I asked how we were different, and I took that as a compliment. I believed him when he assured me he wasn’t marrying a memory.

In the early years of our relationship, friends asked me how it felt to be living with my own Rebecca, referring to the protagonist in Daphne De Maurier’s classic Gothic romance novel. In De Maurier’s sinister tale (and Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 film), a nameless narrator marries a widower, moves into Manderley, his family estate, and is haunted by the memory of the beautiful, charming, apparently perfect first Mrs. De Winter. The new wife lives with a jealousy that eats away her self-esteem, if not sanity, until she learns the true character of the original lady of the house: cruel, selfish, manipulative.

My Rebecca was nothing like this.

It’s too bad our paths hadn’t crossed earlier in life, because I believe we could have been good friends. From her sisters I’ve learned my Rebecca was a “whiz in the kitchen” who had a passion for making pies from scratch. We might have bonded over a common mad love for our nieces and nephews or our affinity for Broadway musicals. We appreciated the value of a good man—a great man. A man who loves and appreciates feisty, strong, passionate, compassionate, and pasty women.

Pasty women who, to outsiders, apparently all look alike.

Like any new bride—and a forty-something bride with a previously married groom—I was prepared to be evaluated at first-time introductions. But in my odd case, navigating reactions could be painful. On a handful of occasions, I found myself an undeserving source of grief when my accusers realized the woman they thought I was had died. Should I try to comfort them? Express my sympathy? Sneak away under the pretext of refilling my wine glass so they can cry in private? No one tutored me in the appropriate etiquette for these scenarios.

In other settings I encountered a law school classmate of Rebecca’s who was offended I didn’t remember her from torts class, and a distant relative who introduced me to old friends gathered for a funeral as “Brad’s wife, Rebecca.” I swallowed the insult when no one blinked at the mistake and said, “Nice to meet you.”

At a retirement party, a woman I’d yet to meet got within inches of my face and announced to the small group around me, “You’re right. She does look like her. You can especially see it around the eyes.” It was as if she was critiquing a painting or sculpture or butterfly pinned in a display case, oblivious to the human being inside.

But it was almost worse when people couldn’t accept the reality in front of them. Like the woman who was convinced she remembered me from someone’s long-ago wedding: “But I know I know you!” Not wanting to embarrass her by announcing the news of my doppelgänger’s demise in front of other strangers, I tried to ease her into a neutral topic of conversation. But as my frustration grew, I was tempted to ask, “Do read Playboy? Perhaps you recognize me from there?” Before I could exercise my questionable wit, her son-in-law pulled her aside on some excuse. They moved almost—but not completely—out of range so that I heard: “Ohmygawd, she died?! THAT’S the new wife?”

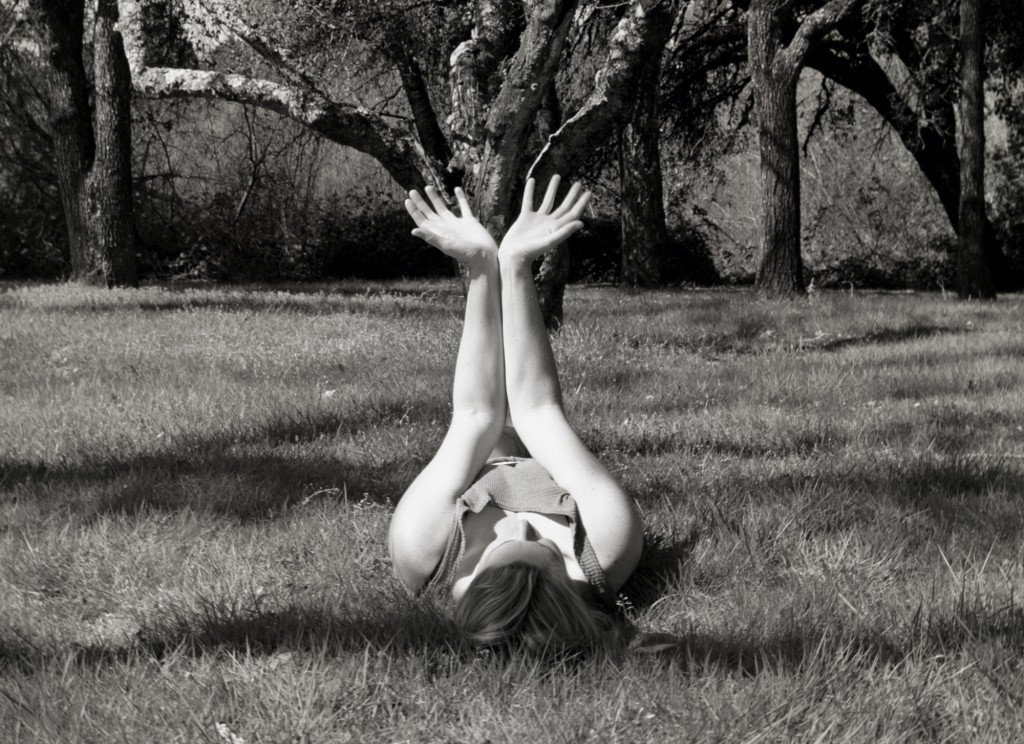

Yes. “That” is me. I am wife number two. Not the replacement, not second best. Just me. I am here! I wanted to shout, with a stomp of my feet. I am still here! Please see me! But, unlike some people, my parents raised me to be polite.

Shortly after my run-in with the across-the-street neighbor, Brad gave me the green light to make his Manderley my own. I began by combining our kitchens, tossing the expired spices that lurked in the pantry’s shadows, keeping the best blender and donating the other two to Goodwill. I then moved through the house, making space in the living room for the cabinet my great-grandfather built by hand and transforming the sunny guest room into my home office.

Finally I made my way to the basement. I turned a storage closet into a wine cellar and hammered nails into a wall to hang our combined collection of gardening tools side by side.

I felt like I was shedding my independent single girl shell as I watched my queen-size bed and three-piece entertainment center being carted out as a donation; they had been my first major “real” furniture purchases as an adult. No turning back now, I thought.

With renewed gusto, I tackled clearing out the bonus room of the basement, thinking it could be the site of a future man cave or guest suite. I sorted or purged chairs with damaged legs, battered bags of softball gear and retired golf clubs, forgotten office files and outdated cell phones; junk, mostly, stood between me and the orderly home I envisioned.

I had understood that Brad had gone through Rebecca’s more personal belongings after she’d passed, so I was unprepared when I stumbled upon a notebook filled with To Do lists scribbled in her handwriting. I held my breath as I scanned the yellowed pages for anything worth saving, then stopped cold when her college ID card slipped out. For half a second I resisted flipping it over to study the photo, then gave into the temptation to settle the debate. There was no gasp of shock, no tingling sensation of facing my long-lost twin. Had I placed my old ID next to hers, I would agree that we kinda looked similar at that age, but not so much that I would have freaked out if I bumped into her on the street. I placed the notebook in the recycling bin and the ID card in a box of items for her sisters to unpack when they felt ready to reminisce.

With an hour stolen here and there, I made progress. But my world, and my heart, stopped the day I found the box with Rebecca’s wedding dress. I didn’t need to open it to imagine the carefully preserved white satin and lace, and I sensed her longing to one day share it with a daughter or niece. I continued to unearth treasures, and among the dog-eared novels destined for the library, I discovered gardening inspiration for the backyard she never got to plant; kitchen remodeling ideas for making her new house into a home; and picture guidebooks of Italy, Germany, and France, destinations for future romantic getaways. I found, buried deep below the fun stuff, workbooks for moving through the adoption process. Diagnoses, treatments, suffering, and early death eclipsed it all. Surrounded by all the remnants of Rebecca’s hopes for creating a family and a home, for living a full and “normal” life, I felt overwhelmed by the enormity of her losses. I sat in the corner of our basement and wept for all of her unrealized dreams.

And then I spent a few minutes weeping for myself. If only I’d met my husband when we were in our twenties, we might have naïvely bypassed our painful misfortunes. Among my own shattered dreams were dashed hopes of having children, and grandchildren, of creating a real family. I could have been Brad’s only bride, his only history. I cried over the possibility that when we all meet up in heaven, Rebecca will get first dibs. I wondered if he ever looked at me and wished I were her. And I hated myself for feeling jealous of a woman who had lost so much, and in the process, had given me everything.

Our husband will never fall out of love with Rebecca; he simply discovered that his heart was big enough to love again. And while I’m not The Love of his life, he is mine. Mine to build a future with, to fill the blank spaces on our walls with new photos of weddings, anniversaries, and vacations. I am sad for him, for the heartbreaking losses he has experienced, yet those same experiences also helped form the man I love. I am grateful for our second chances.

At times I still sense three souls in our marriage, but I believe it’s possible to embrace the “exes” and “formers”, I believe we can thrive when we choose to accept the past and live in the present. For today’s reality is Rebecca is gone, and I am here.

Meanwhile, I’ve grown to make peace with my role in our family dynamic, and I’ve learned to better anticipate the mistaken identity crises and respond in a way that feels appropriate to me.

“I don’t believe we’ve met before,” I say, “but I am pleased to meet you today. My name is Kathleen.”

•••

KATHLEEN GUTHRIE WOODS performed a version of this essay live for San Francisco’s Lit Crawl. She is currently wrapping up work on The Mother of All Dilemmas, a memoir about finding her worth as a woman in today’s world—whether or not she has children. See more of her work at http://kathleen-ink.com/articles/.

Follow

Follow