By Randy Osborne

My forearms and the backs of my hands are faintly speckled and sketched with blood. Like when, in grade school, you twiddled the ballpoint pen between your fingers and let the tip touch paper for quick, light slashes. Like when you made dots by pressing.

These traces on my flesh—they heal and are remade, but they will heal again—can pull a stranger’s gaze, can make him look away. Neither defined enough to signify cutter, nor dug-out enough to say crank sores, the marks mean something else.

Squirrel.

•••

Upon waking, Sciurus carolinensis, the Eastern gray tree squirrel abundant in my Atlanta neighborhood, yawns and stretches. It sees the world in color. Its hands bear vestigial “thumbs.” Its body temperature ranges from 98 degrees Fahrenheit to 102.

Its brain weighs 0.25 to 0.35 ounces, relatively large for a mammal, in proportion to body weight. This is not because the squirrel is extra-smart, but because it has parallax vision (it looks at you with both eyes at the same time to judge your distance, for the purpose of fleeing) and spatial memory (it doesn’t find buried acorns by odor alone—it remembers), and because a squirrel’s keen sense of hearing needs more gray matter. Its ears face sideways, like ours.

The family name Sciuridae is Greek for “shadow of the tail.” Used mainly for keeping warm and dry, the tail adds 17.8 percent of protective value to baseline when raised. Someone has measured this. Below the tail rests a cluster of blood vessels that the squirrel can dilate or narrow to warm up or cool off—no small matter for endotherms, creatures that make their own heat, like us.

You may detest squirrels. Many urban people do, given the raiding of bird feeders that goes on, given the chewing-up of attic insulation, which compromises our own heat-making, and given the mad, kamikaze severing of electrical wires. “Tree rats,” you may call them, ignoring the many differences. I love one.

•••

In June 2012, I was making more money than I had ever made. My first foray into the corporate world, with its murky, ever shifting demands meant a nicer apartment, with a pool and gym. My girlfriend Joyce and I dined at snazzy restaurants. We talked about having kids. My boss flew me out to work in the home office, a skyscraper that gleamed in the San Francisco sun.

Abruptly one afternoon, by phone, I lost my job. Downsized and restructured, I drifted, uncertain about my future. Ours. Although I didn’t realize this when we met a few years earlier, the matter of children was a potential deal breaker, since Joyce half-wanted kids. “Not your willingness, I mean, but whether you would be open to the idea,” she said, vaguely.

I was. With three grown kids from two previous marriages—three, by the way, is also the average size of an Eastern gray squirrel’s litter—I felt ready to consider fatherhood with Joyce. But now I was jobless. Even before, there was a potential snag. Our ages differ by twenty years. The gap is wide enough to worry over, especially considering the already shorter lifespan for men. Twenty years is how long squirrels are estimated to live in captivity. In the wild, only about half that.

•••

In August, a friend asked me to substitute as host of her literary reading series. A simple chore. Welcome the turnout, introduce each of three writers, and wind up the show, good night. But I felt nervous, an impostor. Although I had composed a few pieces that seemed okay, I was not a member of the scene, not a bona fide person of letters. I admired the others as they sped past, trailing bright streamers of irony.

Since I had planned to attend as a spectator anyway—and with, after all, not much else to do—I said yes.

We strolled in the near-dusk, making our way toward the coffeehouse. I saw a few people I recognized, no doubt bound for the same place. Suddenly, someone cried out, pointing to a spot in the street beneath a massive oak. We hurried over.

A tiny curlicue twisted slowly on the asphalt, its sparse fur (pelage, I would learn) unruffled, eyes open. Blood seeped from the nose and mouth. Delicate whiskers (vibrissae) twitched. About twenty-five feet above us, we spied the leafy mass of nest (drey).

Joyce’s artist friend Hilary retrieved an old tee-shirt from her car. She lifted the squirrel from the pavement as if handling smoke. Her fingertips arranged the fabric around its wee body, which all but disappeared. Most squirrels don’t survive their first year, and this one fell hard. Internal injuries, most likely.

Of the night’s event, I remember only the end, when Hilary approached me with the bundle, a cleaned-up nose peeking out. She had asked around—nobody wanted to take the squirrel home. Made sense to me, hardly a fan of the rodent class. Everyone probably recalled well, as I did, all the baby-bird failures of the past and couldn’t face another. Hilary tucked the corners, a final tidying of the package.

“It’s a boy,” she said and held him out to me.

At home, after a Google search, I witnessed myself driving to Publix, where I asked the pharmacist for a batch, please, of one-cc, needle-free syringes. Then to the infant-care aisle, where I seized a liter of Pedialyte. Next, PetSmart for a can of Esbilac puppy-milk powder.

Removed from his burrito-style wrap, he fit in my palm like a miniature doughnut with a licorice-whip tail, or like an exotic, oversized insect. He kept his eyes closed, as if to say either, “Let me get some rest, it’s been a long day,” or, “I can’t bear to watch what the human is about to do to me.”

I loaded the syringe with Pedialyte. Here goes.

As soon as he felt contact, he gripped the nozzle with bony hands and sucked, eyes half open now, gulping, as my thumb delivered a slow push.

Baby squirrels in the wild gain sixteen-fold their weight in two months. In humans, this would be comparable to an eight-pound baby reaching 130 pounds in the same period. The squirrel mother’s magic milk consists of twenty-five percent fat and nine percent protein. Compare Esbilac powder, stirred into Pedialyte: forty percent fat and thirty-three percent protein. Close enough, it turns out.

During those first weeks, Bug took six syringes of formula at each meal, with feeds about four hours apart. He would drain the first syringe, swat it away, and grope frantically for the next. In about a month, he was downing less formula and rejecting the syringe after emptying two or three. He munched bits of apple. A few weeks later, diced raw green beans, and broccoli stems. Shelled nuts. Before long, he was cracking into them himself.

•••

“Imagine,” the wildlife rehabber tells me, “having a two-year-old child who is emotionally dependent on you—only you, they latch onto a single caregiver—and who will never grow up. I mean never.”

I think of my kids as two-year-olds. Hadn’t I wanted them to grow up? Of course, I did. Yes. And: no.

The rehabber is realistic in describing my options. She is predicting from experience how things will go. Did she say “emotionally”?

Until her, I didn’t know that people exist who specialize in the process of returning squirrels to their natural habitat, after well-meaning humans like me snatch them out.

“But it doesn’t always work,” she says.

I keep her number.

•••

“The majority of mammals live solitary lives; estimates suggest that at least 85 percent of mammals can be classified as asocial animals that aggregate only briefly at a seasonal food source or to mate.”

—Michael Steele and John Kropowski, North American Tree Squirrels (Smithsonian Books, 2001)

Joyce and I watch squirrels jump, dart, and scurry in the park. On a flat surface, squirrels can travel as fast as 16.7 miles per hour. Their crazy trajectories, never in tandem or together, bisect each other across the grass and up the trunks of trees. Lyrics from a Patti Smith song come to me, the one she wrote for Robert Mapplethorpe as he was dying of AIDS. “Paths that cross will cross again.”

In the traffic behind us on North Highland Avenue, we hear a pop—the sound a plastic bag with trapped air makes as tires roll over it.

Together, we turn. The squirrel lies near the center of the road, still alive, hands clawing pavement, unable to drag the rest of its body. After a few seconds, stillness. A light, almost merry wave of the tail, goodbye.

How far away the curb must have seemed, in that squirrel’s fast-fading, parallax, big-brained vision. The Stephen Dobyns poem, “Querencia” (Spanish for “a secure place”), describes a bull tormented in the ring as the audience cheers.

Probably, he has no real knowledge and,

like any of us, it’s pain that teaches him

to be wary, so his only desire in defeat

is to return to that spot of sand, and even

when dying he will stagger toward his querencia

as if he might feel better there, could

recover there, take back his strength, win

the fight, stick that glittering creature to the wall …

The glittering creature in this instance is not a matador but an SUV, now a block away. No bloodthirsty crowd, only a few pedestrians who seem not to notice what happened. Maybe the driver didn’t, either.

One of the many reliefs of no longer owning a car is that I don’t have to worry about killing anything with it, but I remember instances. A thump, the glance in the rear-view mirror. That wad of flopping misery. My sick, jarred sense of a fatal suffering so great and so nearby, yet unfelt by me, impossibly, its cause.

In Dobyns’s poem, the afternoon proceeds messily, the bullfighter proves inept, and “everyone wanted to forget it and go home.” Joyce and I do, too. Cars make sad arcs around the squirrel corpse, which I know I should relocate before it’s transformed into a meat rag.

The squirrel’s up-tilted, almond-shaped eye, with that tight rim of lighter hair, is still moist and shiny. I’ve had my eye inches from Bug’s. Like this eye, his are strong-coffee opaque, yet suggestive of a depth.

The body is warm in my hands. I think of Hilary’s fingers. I feel crushed bone pieces, many bone pieces, jostle amid the limp flesh. Before situating it in the grass, I sneak a glimpse at the lower abdomen, the pink nub there. Male.

•••

Tonight’s sunset must be glorious to somebody. On Elizabeth Street, I stand gaping, unfazed, at the orange-scarlet and indigo riot in the sky.

I’m hungry.

Scientists at Wake Forest University devised a chamber with an oxygen analyzer, put a squirrel inside, and gave it something to eat. The idea was to find out whether squirrels know which nuts are smartest to consume, i.e., which offer a “net value” (calories) that justifies their “handling costs” (effort taken to split the shell, determined by oxygen use). As you may have guessed, they do know. They budget every sliver of energy. Gray squirrels do not hibernate, which means that, even in the harshest winter, they forage. Searching and often not finding.

Squirrels budget, and so must we, the privileged. Dinner done—burritos, cheap New Zealand white wine—it’s playtime for Bug. He’s ready. He charges madly up and down the levels of his tall cage. We do this twice a day, to keep his skeleton supple and because I can’t resist him.

Metabolic bone disease is the main cause of death in captive squirrels. Like humans, when they are not exposed to enough sunlight, they make no vitamin D and can’t absorb calcium. I send away for Bug’s food. The fortified blocks, in sealed plastic bags from Florida, consist of pecans, protein isolates (whey, wheat), and thirty other ingredients, including vitamins D, K, E, as well as B-1, -2, -3, -6, and -12, with all the important minerals. A month’s supply, twenty-five dollars.

He springs out. Perches on my shoulder, rotates to inspect the room. Hops atop my head.

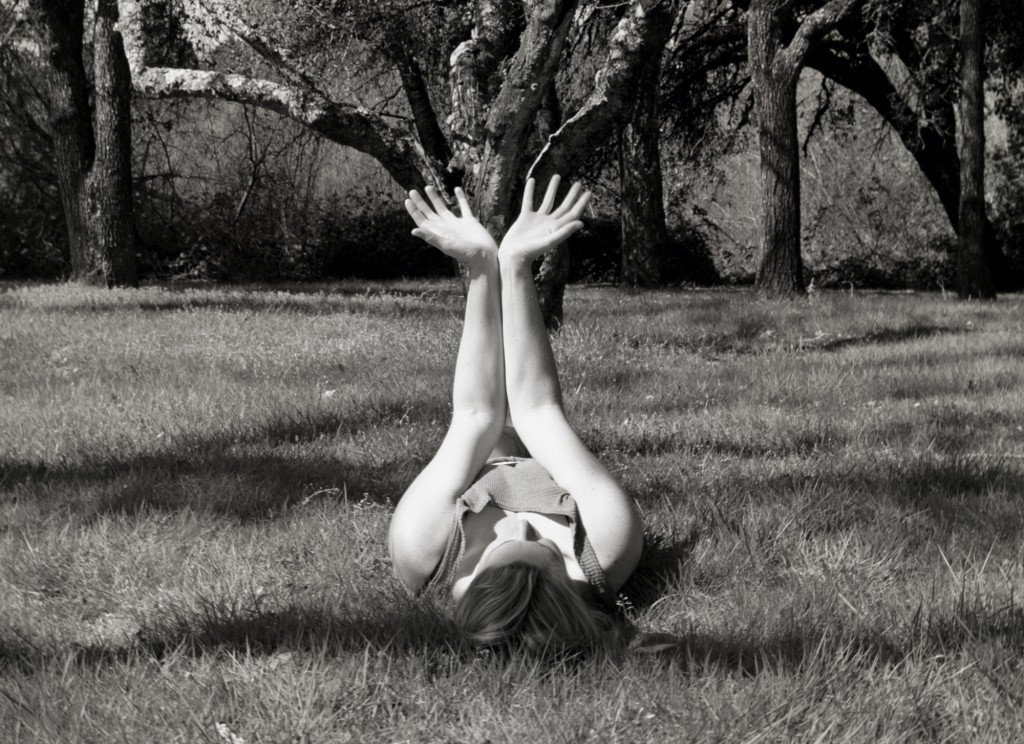

For the next hour, he scrambles over and across my arms, legs, hands, and torso—somehow he knows to avoid my face—pausing only to wrestle. This involves tumbling between my hands, losing then regaining the top position. Over and over.

He nips, and I feel the promise of his incisors, but not their full gift. The damage is done by his inward-curved claws. Evolved for tree bark, they slice and puncture flesh. I endure this abuse in trade for the moments between, when I touch his pelage, soft belly, and cold wet nose. His tail, plumy, snow-fringed, sifts through my fingers.

I offer a hazelnut, which he snatches and “buries”—finds a cranny in the sofa or an empty shoe or even a vacant pocket, jams the nut in as far as possible, and pats around the area. Scatterhoarding. During play, he will not stop longer than a few seconds.

In the mornings, though—yawn and stretch—he positions himself on the cage’s upper tier, where I can reach him, tucks his snout into the crook of my thumb, and submits to a few minutes of drowsy massage. As if he knows breakfast follows. He does know.

•••

One of Emerson’s lesser-known poems, “Fable,” pits squirrel against mountain in an argument—the dialogue of big versus small, hashing out superiority. Says the squirrel,

But all sorts of things and weather

Must be taken in together

To make up a year

And a sphere.

And I think it’s no disgrace

To occupy my place.

It reminds me of Bergson’s Introduction to Metaphysics, where he writes that “many diverse images, borrowed from very different orders of things, may, by the convergence of their action, direct consciousness to the precise point where there is a certain intuition to be seized.” But toward what is Bug directing me? What am I expected to seize?

•••

Squirrels mate twice per year, once between December and February, and again in summer. Estrus lasts eight hours. All day, males chase the female, who copulates with three or four. Each gets about twenty seconds. The older, dominant ones usually prevail, but not always. In “breakaways,” the female escapes to a secluded area for a few minutes of peace. She mates with the first male that finds her.

Bug’s downy testicles are huge, about the size of butterbeans, loaded with baby-making potential. In “active” mode, his balls weigh seven grams. They shrink to one gram when the season of lust passes. Why shouldn’t he get his chance? Even if it’s with a girl who’s just tired of going through the paces with more virile types and willing to take whatever guy comes along.

But I fear for him in the wild. Predators hover and lurk. Hawks and owls. Cats, foxes, and snakes. The hodgepodge of parasitic species that want him includes six protozoans, two flukes, 10 tapeworms, one acanthocephalan (thorny-headed worm), 23 roundworms, 37 mites, seven lice, and 17 fleas. There is also the odious botfly, which lays its eggs under the squirrel’s skin. Larvae become disfiguring lumps the size of olives, called “warbles.” Eventually, the pupa drop out of dermal holes to finish growing in soil.

What’s mating worth?

•••

In the fall of 2013, I see reports of squirrel migrations in north Georgia. A bumper crop of oak acorns in the previous year led to a high birth rate, followed by a mild winter and rainy spring, which caused the supply of nuts from oak, beech, and hickory trees (mast) to dwindle. That’s one theory. Less obvious forces could be responsible. Naturalist P.R. Hoy of Racine, Wisconsin, reported gray squirrel migrations across his territory during three satisfactory mast years—1842 (four weeks, a half-billion squirrels!), 1847, and 1852. No one knows why.

In more recent history, our state has not seen a migration of 2013’s magnitude since 1968, a year when other stories pushed aside news of wandering Sciuridae. The war in Vietnam raged that year, with the Tet offensive in January and the My Lai massacre in March. Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed in April and Robert F. Kennedy in June. President Lyndon Johnson gave up on seeking a second term.

Quieter history was made in Greenwich Village. “In retrospect, the summer of 1968 marked a time of physical awakening for both Robert and me,” writes Patti Smith in her memoir. They had begun to understand what was possible, and what was not.

•••

Winter’s almost here. Joyce and I continue our talks. I bring up parenthood more often than she does, she who has yet to become a mother (nulliparous). At the same time, I wonder about my fitness for doing the dad thing yet again.

For more than a year Bug was, other than Joyce, the last thing I saw before sleep, and the first thing I saw in the morning, his cage and towel “nest” situated opposite our bed. I woke to the squeaks when he dreamed.

At odd moments, almost every day, memories of him rise. Images. Sniffing inside my ear. Smacking on a chunk of avocado, his favorite. Balancing on my hand, his teeth scraping my thumbnail. Nuzzling me as, from the other side of the bars, I trace his flanks and ribs. I feel his heart tapping.

I see him leap from branch to branch in the forest canopy, his body made for this. The “overstory,” botanists call the green ceiling, limbs almost entwined, leaf and twig so close together that the vibrissae of tree squirrels grow longer than those of ground squirrels, the better to detect what’s near. There’s an “understory,” too, down where I am. Paths that cross will cross again. I picture him in mid-air.

•••

RANDY OSBORNE writes in Atlanta, where he teaches fiction and creative nonfiction at Emory University. He’s the director and co-founder in 2010 of Carapace, a monthly event of true personal storytelling, and staff writer at BioWorld Today, a daily newsletter that covers the biotechnology industry. Represented by the Brandt & Hochman Agency in New York, he is finishing a collection of personal essays.

Follow

Follow