By Katie Rose Guest Pryal

“What do you want to talk about today?” says my dance teacher.

I say, “I’m getting depressed again.”

My friend Ariane and I call our therapists our “dance teachers” to protect our privacy. It’s simpler to say, “I’m heading to my dance lesson after this” when talking to Ariane on the phone at the grocery store. Or “Let me tell you what my dance teacher said” when we’re at the coffee shop.

Plus, codes are fun.

The code works because the idea of either of us actually taking a dance lesson is preposterous.

After I tell my dance teacher how I’ve been feeling, I say, “I hate that I didn’t notice sooner. It hitched a ride in on something else.”

She asks what that something else is.

“That my career is a failure,” I say.

She nods, waiting for more.

“This week, though, the depression finally became obvious. It touched all the same old pressure points.” I tick them off, one by one. “I felt like there was no point in trying. That nothing I do matters. Because it’s me that’s a failure.”

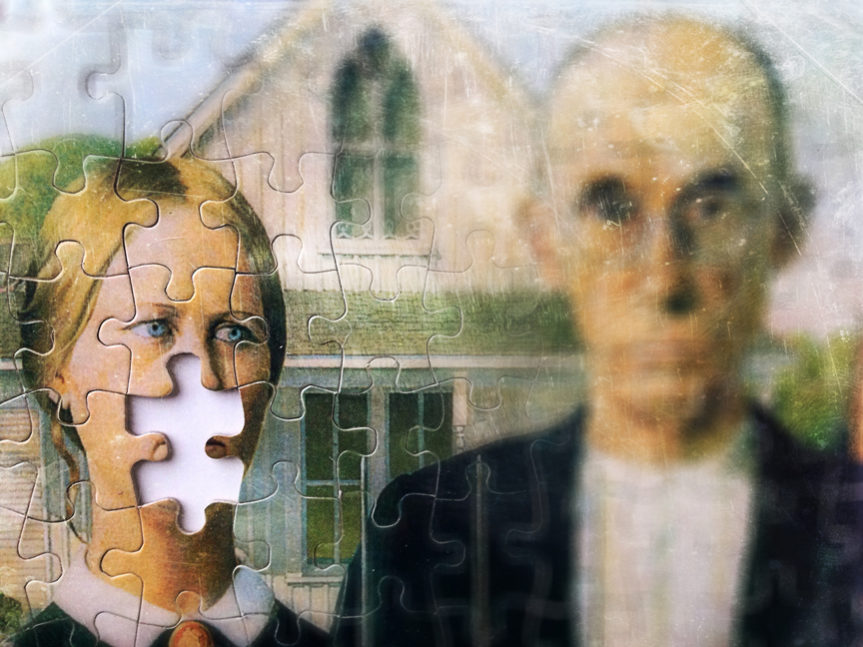

When I look inside myself, I see a large, ugly hole where joy should be, and I’m afraid I’m going to fall into it. That’s a Grade-A emergency, and I know it.

This isn’t the first time I’ve been depressed. I tell my dance teacher that I will reach out to my psychiatrist to follow up about treatment.

She digs deeper. “I wonder why it was able to hitch a ride on your career insecurity.”

I tell her I don’t know.

Then she asks the strangest question. “What is your core belief about yourself?”

“I have no idea,” I say.

•••

In the cinematic masterpiece Top Gun (1986, dir. Tony Scott, RIP), the main character, Maverick, has an ugly hole inside himself that he can’t fill. He has the hole because, when he was a child, his fighter-pilot father died—which would wound anyone. But Maverick’s father died in battle, and the Navy blamed him for his death and the deaths of his compatriots.

In his own career as a navy pilot, Maverick has lived under the ugly shadow of his father’s ignominy. And it really did affect his career: “They wouldn’t let you into the [Naval] Academy because you’re Duke Mitchell’s kid.”

[Here come the spoilers.]

Maverick’s ugly hole wreaks havoc in other ways, ways that Maverick doesn’t see: despite being an excellent pilot, he takes unnecessary risks. His perceptive co-pilot can see it, saying at one point, “Every time we go up there, it’s like you’re flying against a ghost.” Another pilot, Viper (great name, right?), says to him, “Is that why you fly the way you do? Trying to prove something?”

The answer is yes. Maverick is perpetually trying to prove that he’s more than the embodied shame of his father’s wrongdoing.

That’s why he leaves his wingman in the opening scene, causing the pilot, Cougar, to lose his cool and turn in his wings. That’s why he screws around with enemy pilots, taking Polaroids in a combat situation.

That’s why he radios the control tower with the cheeky request: “Tower, this is Ghost Rider requesting a flyby.”

And then he ignores the response of the tower boss—“Negative, Ghost Rider, the pattern is full”—and buzzes the tower, causing havoc and getting himself, and his co-pilot, in trouble with his commanding officer.

Maverick’s pattern, the one he keeps relentlessly repeating, is recklessness and self-sabotage.

Maverick thinks he knows what he needs to fill that gaping hole: win the Top Gun flight school trophy. He believes that if he can just win the trophy, he can toss it in that hole left by his father’s shameful death, and the hole will close.

He doesn’t win the trophy.

But winning the trophy wouldn’t have filled the hole at all. Instead, in a moment of truth, he figures out that he doesn’t need to give the finger to all of naval aviation because they look at him and only see his father’s sins.

Instead, Maverick needs to “stick by his wingman,” an actual flight behavior that has become metaphorical: to stop taking needless risks and be someone others can count on. Not a maverick (heh) at all.

Truly, it’s an excellent film.

(There’s also volleyball.)

But here’s the hard part, what’s not on the screen in Top Gun, but what those of us with dark holes know to be true. Perhaps Tony Scott, who died by suicide, knew this to be true as well.

Even when Maverick figures out what he needs, even when there are hugs and cheering and romance, the hole isn’t filled. His father is still dead, and the death will always be shrouded in a miasma of disgrace.

Nothing can ever fill that hole. Ever.

•••

We toodle along making terrible decisions trying to fill a hole we don’t even know exists.

I’ve done it again and again. I keep doing it, and I can’t seem to stop.

When I was younger, fresh out of my doctoral program, I took a job as a lecturer. “Lecturer” is a non-tenure-track position, and it is also code for “crappy job” in academia, my then-chosen career path.

After taking the job, I spent the next seven years on a fruitless quest for a tenure-track job.

I overworked at a ridiculous pace. Each year, I published at least two articles and presented at a minimum of three conferences. After a couple of years, as my professional reputation gained traction, I was invited to deliver keynote talks or to chair featured sessions. I was climbing the ranks everywhere except in my own institution.

There, I remained a fake professor. A fraud. A failure. Illegitimate.

I believed that I was a failure because I never landed the holy grail of academic jobs. It didn’t matter that the job market for tenure-track jobs had shriveled to nothing by the time I graduated. The fault was mine.

Like Maverick, I thought I knew what I needed to be happy. To win that thing, I behaved recklessly. My fruitless quest hurt me: it kept me up late nights and away from my tiny children too many weeks of the year. I missed my son’s first steps because I was at a conference delivering yet another presentation on my research.

If I could just earn tenure, I believed, I would be a real professor, no longer a fraud.

After seven years in higher ed, I gave up. It took that long to realize that I had been trying to fill a bottomless hole. The hole had nothing to do with tenure at all; it had to do with me feeling ashamed. No matter how many articles, presentations, and professional achievements I tossed into it, the hole remained empty.

Within three months of quitting my job, I was able to accept that the hole was a part of me, and I put it behind me. It would take years before I returned to academia on my own terms.

I was free, I thought back then. But I was wrong.

•••

I first learned about holes from my friend Ariane’s perceptive aunt, F., who always seems to know how you are hurting and to say the words you need to heal.

F., who knows something about Ariane’s difficult past and my own, said this: You have holes, but you can never fill them. You can’t fill them because they’re not in the present—they’re in the past. Therefore, they will always be there, in the past. You can’t go back and fix them.

You just have to learn to live with them.

When I first heard F.’s words, I said to Ariane, “That’s dark as fuck.”

“Yeah,” she said.

After my recent dance lesson, I talked to Ariane about holes, trying to make sense of things.

She said, “Unless Dr. Who is going to show up and change your past, the holes are just there.”

But it feels so hopeless, I told her, to look back at my past riddled with holes.

Ariane said, “What you’re feeling is grief. And it is really fucking dark.”

The last stage of grief is acceptance. Accepting the holes and letting them go.

•••

Real life is never as simple as Top Gun. You don’t leave your singular hole behind and move on, well-adjusted and Okay. The pattern repeats itself over and over, and it can take decades to even spot it.

After I left academia, I began a career as a writer. Before I ever earned my doctorate, I earned my master’s in creative writing. Once I was free of academia, I was in a position to give my writing a real shot. And it worked.

I submitted my first novel, and a small press accepted it. And then the same small press accepted my second novel. Two novels published. I was over the fucking moon.

I also wrote for magazines, lots and lots of them. I wrote textbooks for three different Very Respectable publishers. I wrote all day and night, publishing five to six magazine pieces a month in addition to writing books.

But when the small press declined my third novel, everything came crashing down.

My novels failed (yes, that’s what I believed), and so I’d failed.

I was so insecure that I couldn’t see that I’d achieved what many people only dream of: two published novels, a number of textbooks, and a thriving freelance career.

•••

I play tennis as a hobby. For a few years, though, I played on a USTA team where the captain created an atmosphere where the players had to scramble and fight for starting positions.

However, the captain seemed to view some players as legitimately good players even if they lost now and then. But not me. I needed to perpetually prove that I was not a fluke. Not a fraud.

And the only way to do that was to never, ever lose.

As the seasons wore on, even friendly matches stopped being fun. The captain wanted us to report scores to her every time we played. If I—if any of us—lost while playing for fun, we might lose our spot in the lineup.

Eventually came The Season. My doubles partner and I were undefeated. We won our crucial playoff match, and our team was off to the state championships.

At the USTA state championships, there are five matches in three days. In my mind, I had to win all five. I had to. We won the first. The second. Two-a-day matches in the North Carolina summer heat is brutal, but we pressed on. On day two, we won the third match, and the fourth. That night, after four matches and two days, I went to bed early with a horrible headache. But I pressed on.

The next morning, during our fifth and final match, the court temp was hovering around 110 degrees. Worse, there was no nearby water.

We won the first set easy, our rhythm the same perfection as it always was. But then, at the beginning of the second set, I felt chills coming on. Okay, I thought. Chills I can live with. But then I ran out of fluids after drinking both of my forty-ounce water jugs.

I should have stopped the match and refilled my water in the gymnasium, a twenty-minute walk away. But I didn’t want to lose our rhythm. So I pressed on.

Next, I started seeing spots. Then, I stopped being able to feel my feet. Soon after that, I started feeling nauseated.

I should have retired the match. But I pressed on.

My body began to break down. Dizziness set in.

We lost the match in a tiebreaker.

After the match I passed out, vomited, and lost consciousness. I’m not sure how long I lay there in the grass before the ambulance arrived. I owe my life to a teammate who is a nurse and acted quickly, stripping me of most of my clothing and packing me with ice to lower my temperature.

Heat stroke is deadly. Once you have heatstroke, you are past the point where drinking water can help you recover. The only thing that will save you is IV fluids and rapid cooling, and even then you can end up paralyzed or with other long-term or permanent damage, for example, to the brain.

My long-term damage was to my brain. For months, I couldn’t drive. I would get lost just walking around our neighborhood, calling my husband sobbing because I couldn’t find my way home. I had only about three hours a day when I felt even close to fully functional. The rest of the time I spent in a daze or sleeping. Any heat, at all, made me nauseated.

I nearly died trying to fill a hole that no amount of winning could ever fill. I was afraid that I would never be good enough to be a real member of the team.

It wasn’t until I talked to my dance teacher last week that I could give the hole a name. Tenure, writing, tennis, and more—there are so many more. But they are all the same.

•••

The second hardest thing about holes is figuring out that you have them. The hardest thing is figuring out what they are.

Holes are easier to find if you look for what they’re driving you to do. Think of Maverick’s reckless control-tower flybys. Or me pushing myself so hard I end up in the emergency department. Look for the “If-I-can-justs.”

If I can just get a tenure-track job, then I will be a legitimate professor and no longer be a fraud.

If I can just have a traditional press publish my novels, then I will be a legitimate writer.

If I can just win all of my tennis matches, then I will be a legitimate member of the team.

“If I can just”: the template for finding the devil on my back.

I shared the if-I-can-just theory with my dance teacher, and we used it to talk about my current feelings of failure. Right now, my agent hasn’t been able to sell my current book, a book I’ve hung my hopes on. (Reader: never count on anything in publishing.) How I’m a failure as an author. Worse, I’m a fraud.

How I’ve lost touch with my editor contacts over the past couple of years, and I can’t seem to place any pieces in magazines, and I’m a failure.

How all of my ideas have evaporated.

And more.

She tried pointing out my successes, but we both acknowledged that logical arguments fall down the hole just like everything else.

But then it hit me—I knew what was driving me. I said, “If I can just publish one trade book with a large publisher, then my writing career will feel legitimate.” I admitted that this if-I-can-just was ridiculous and overly specific and that it wouldn’t solve the underlying problem of my feelings of inadequacy. And I felt proud of myself for figuring out what was wrong with me.

She nodded, seeming to accept my assessment. (Reader: She did not accept my assessment.)

Then she hit me with a whammy. “How long have you been driven to seek other people’s approval?”

“What? No.”

That didn’t sound like me at all. That sounded like a weak and small way to live. Her words reminded me of Wormtail from Harry Potter, all beseeching and whiny and lacking in dignity. It didn’t jibe with my self-image. I am not a suck-up.

But my dance teacher was right. All of the holes, one after another, were all manifestations of the same hole. I just didn’t realize it until my dance teacher hit me with that two-by-four of truth. That two-by-four hurt.

My dance teacher continued, “You believe you’re never good enough.”

That one I already knew. But I was starting to realize that I compartmentalized the belief, tacking it onto specific contexts. Not good enough in academia. Not good enough in sports. Not good enough at writing.

Forever chasing my tail.

My dance teacher wanted me to call my devil by its name.

“How long have you been driven to seek other people’s approval?”

“Always.”

•••

When my dance teacher asked me, “What is your core belief about yourself?” I told her I didn’t know.

I’ve spent days pondering this question. At first, I thought I didn’t know the answer because I’ve always lived for other people.

But now I do know the answer: I’m a person who overachieves in order to make myself feel worthy of love.

This hole has driven me for as long as I can remember. But I’m strangely attached to it. If I don’t have this monster nipping at my heels, then who am I? Without it, will I still have the drive to succeed that has been a part of me since I was a child? If I let it go, I will I slip?

What is my core belief about myself?

I don’t want to live like this anymore. It’s awful. Through the years (and years and years) of chasing legitimacy, of trying to fight feelings of being a fraud, I’ve also believed, deep inside, that I’m not worthy of love.

My dance teacher told me that this hole formed early. She told me that it wasn’t my fault. It’s there, in the past, and it will always be beyond my reach.

I have risked my relationships, my very life, to prove I’m worthy of love, friendship, and respect. I won’t, I can’t, do that anymore.

I know what it feels like when I’m getting depressed. It’s happened before, and I know what to do to make sure I come out okay.

And now I know what it feels like when I’m tossing pieces of my soul into a bottomless pit. I’m not sure what to do, yet, except be vigilant.

•••

KATIE ROSE GUEST PRYAL’s work has appeared in Catapult, Slate, Full Grown People, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and more. She’s the author of more than ten books, including the IPPY-Gold-award-winning Even If You’re Broken: Essays on Sexual Assault and #MeToo and the bestselling Life of the Mind Interrupted: Essays on Disability and Mental Health in Higher Education. A professor of law and creative writing, she lives in Chapel Hill, N.C.

Follow

Follow