By Glendaliz Camacho

Letters from JR (2012)

On a February night in 2012, there was a knock at my door. When I looked through my door’s peephole, I saw a young man in my hallway. My neighbor’s son from upstairs. I figured that he was going to ask if I had heat or hot water or to borrow something, so when I opened the door and heard him say, “I’ve been wanting to talk to you for a long time. Are you seeing anyone?” I put my hand up for him to stop talking and told him I’d get my keys and come out into the hall.

JR stood on the second step of the landing between our floors. He was built like the high-school football player he’d been—thick neck, broad shoulders, muscular legs. By the way his eyes, the color of wet soil, drifted up into a corner of the ceiling like a student remembering what the textbook said, I could tell that he’d rehearsed this in his head until he’d finally built up the nerve to do it. I knew what I should say. Point out our age difference—he was twenty-three, I was thirty-three. Point out how different we were as people—he wore his pants three sizes too big and I’d once heard him have a yelling match in the front of our building with his ex-girlfriend, while I stopped liking guys who wore baggy jeans in ’96 and kicked my previous boyfriend out for being too chaotic.

It would have been easy, too; it would’ve taken me all of a minute to say, This is sweet but no thanks. Instead, I gave him my phone number.

Breaking both cardinal rules I’d laid down the next day in his bedroom—this is not a relationship and discretion was required—JR and I went on dates, he met some of my friends, and we held hands in public. I played Otis Redding songs for him, introduced him to Carlos the Jackal via a mini-series, and read him Thich Nhat Hahn. He’d drive me to work and pick me up almost every day and make me tea in the evenings.

To see myself through his eyes was to witness feats of sorcery. The thrill was in coming up with more and more things to expand and amaze him with. All random things that I was into that he’d never been exposed to or never had the freedom to express interest in because of the street life he was drawn to. If I stopped too long to think about it, I knew I would find my relationship with JR to be unsustainable, but I swatted the thought away in exchange for how good the attention felt.

One evening, detectives knocked on JR’s door. I lied and said he wasn’t in. They left their card, saying they just wanted to ask him a few questions. JR admitted he’d committed a robbery. There was a good possibility it was caught on video. A week later, he decided to turn himself in.

We spent that evening sitting on the steps of the elementary school that we’d attended, across the street from our building. We had started out the same—two kids with cartoon backpacks and fresh pencils. As much as I joked that my School of Making Better Men was closed, I believed that boy could reemerge, the boy that went to the same gifted junior high school I did and earned a college football scholarship. From the corner at the top of the hill our building sat on, I watched him walk away until he disappeared into the precinct. He was sentenced to five years.

We wrote each other almost every week, at first. JR’s first letter began, “I miss and love you so much. I wish and pray I can go home to see, hold, and sleep with you again.” Another letter continued, “I also find myself trying to ascertain how or why you love a monster like myself. I know I haven’t shown you that side of me, but based on my way of living alone, it should’ve kept you at a distance from me.”

In another letter, “I still can’t believe I’m so lucky to have a woman like you on my side. My shrink tells me that I should call it a blessing, but I call it luck, because blessings have nothing to do with love. Luck has everything to do with it. Then he asked me how do I figure that and I explained, love is luck because not everyone in this world will ever know what love is, nor will they ever experience it. It’s like stumbling upon money in the street. That’s not a blessing, you was hit with enough luck to find that money.”

He closed another letter with, “please don’t leave me alone because without you, I’m just the same old monster I’m known to be.”

After a few months, I stopped writing back.

First letter from John (April 2013)

One afternoon, I checked my OK Cupid account to find a message from JLRodriguez. “Had I recognized you for you I never woulda stopped, but I did, and you probably already got a message that I did…so I will play this however you want me to,” it read. I had randomly popped up on his matches, and he didn’t recognize me until he was already in my profile.

I recognized JLRodriguez as John, a poet I met at a reading in the lower east side two years prior. We’d already been connected on social media, but the reading was our first interaction in real life. He leaned in conspiratorially and asked what happened between me and a publisher that caused the short-story anthology I was editing—that included one of John’s stories—to come to an abrupt halt. Wary, I gave John a diplomatic answer, something about my sense of timing with the publisher’s not being compatible. We didn’t speak again until a year later when we were reading at the same event. We were cordial, nothing more.

In his message, John closed with, “I’m looking like you are, and you look good. At any case, I do hope you find whomever you are looking for.”

I got called out on something I thought I’d hidden well. I was looking. I had been tirelessly looking since I was a child: for answers, love, approval, freedom, happiness. When I found some form of these things—in a conversation with my father, in a new love interest, in an acceptance letter—I sought it out in another way—spirituality, a new love interest, an acceptance letter to something else. Contentment is only a plateau, never a permanent state.

I liked that John offered to meet me on this plateau, as a fellow seeker, but with the openness to know that we might not remain there. If, scrolling through online profiles, I would’ve seen and recognized him, I also would’ve passed, but there was some significance to my appearing on his feed. One that was worth exploring.

Love letter from John (June 24, 2013)

On our first date, John and I had lunch at a Mexican restaurant that had a photograph of Marilyn Monroe on the bathroom wall. I told John I had been reading about the siren archetype and Marilyn Monroe, the prime example. I didn’t tell him that I took a photo of the picture thinking it was a good omen. We talked about Mourid Barghouti’s memoir and Rita Moreno’s autobiography in the park across the street from the restaurant. He gave me a tour of the college campus where he taught freshman English composition courses. It was one of the best dates I ever had.

John was the type of guy to listen to me over the phone so intently, I would ask if he was still there. One day, when I was marooned on my couch with a fever, he brought over tea, Gatorade, and croissants. We often spent time wandering through museums or at readings. He’d send me YouTube links to Wu-tang mashups and I’d send him Robi Rosa or Florence and The Machine songs. He introduced me to Vampire Hunter D and Dungeons and Dragons alignments. I was on equal footing with him intellectually and emotionally, standing on that plateau of contentment. If there was a right way to do a relationship, this was the one I’d gotten the most right. JR was the last page of Act I and John was the first page of Act II.

John was also the type of guy who when I ran out of toilet paper or Brillo pads, brought it up constantly as something that should never happen to an adult. In his thirty-nine years, he’d never once let that happen. The first time I made a meal for him—vegetable lasagna—he said that it was almost, but not quite, as good as his mom’s. In social situations, things could go either way: he was sweet and inquisitive or visibly uncomfortable until he was a block of ice. I wrestled with these pros and cons, but the pros still far outweighed cons.

When I was accepted into a week-long writing workshop in Berkeley, John dropped me off at the Airtran at JFK Airport. We hugged and kissed. “It’s just a week. I’ll see you Monday,” he said. A couple of days later I received a letter via email.

My Glendaliz:

We are far now, so very, and I want you to know how wonderful you make everything.

More than that day, when I saw that picture and wondered who was that beautiful woman; more than when I knew who she was; more than the red-cheeked rush of wonderment in writing you; more than reading your acceptance; it was your willing hand in mine.

You made me feel worthy of love. No one else ever has. It was always me dreaming, forcing the clichéd longing of pseudo-romance. You welcomed me and accepted me and for that, more than anything else that I have experienced, I love you.

You make loving so easy. My time, my concern, and even my Gmail password— it comes as no surprise that I share these things with you, that you find me good at sharing, at noticing, and that you are great at reading me, that you understand, and are willing to deal with the strange seeds watered around me.

With all my love,

Your John

I called to tell him he was the absolute best for sending me a love letter. We talked for about an hour. I can’t remember about what exactly, mostly about how things were going for me in the workshop. It was the last time that I ever heard his voice.

When my week in Berkeley was drawing to a close, my instructor pulled me aside during a break from our workshop and told me John was dead. His mother’s body was found earlier in the week, in her apartment, a hammer next to her bed. John was found a couple of days later when he never checked out of a hotel room where he slit his wrists in the bathtub. When I received his letter, he had already killed his mother and I imagine he had already decided he was going to kill himself.

That OK Cupid message, at first so ripe with fate, now seemed like nothing more than a cosmic joke, a lesson sent by a god in a Greek tragedy to humble me. I reread his letters daily. So many things had to align for John and me to meaningfully cross paths: algorithms, previous break-ups, the science behind what we found attractive. I kept regressing down that line of thinking until it seemed possible that even our parents leaving their respective homelands were part of this enormous web that extended further and further into history itself. If this wasn’t an aleph, it was the closest I ever came to a moment where every thing was visible at once, and painfully so. It was overwhelming to grapple with thoughts of chance, fate, and the way time moves more like nesting dolls rather than in any linear fashion, all while crying, making John’s final arrangements, and trying to meet the daily demands of work and parenting.

I did, however, begin to feel that there was still significance in joining John on that little ledge of contentment, beyond notions of good or bad. There is a quote by the sorcerer Don Juan Matus, from Carlos Castaneda’s books, that says, “The basic difference between an ordinary man and a warrior is that a warrior takes everything as a challenge while an ordinary man takes everything as a blessing or a curse.” The challenge for me was to hold on to goodness and mercy, and the world as a place where these things still existed.

Something in John’s letter prodded me. “My time, my concern, and even my Gmail password.” A list of things he’d given me, except for the password. Yet, here he was saying I had it. John was a poet and he had established a rhythm here, then disrupted it. One night, I was up with newly acquired insomnia when I remembered that he’d once asked me for a favor. He’d given me his Submittable password and asked me to send his manuscript to a publisher. I typed that password into his email and it worked.

John had emailed himself a letter and addressed it to me. The subject line was “just in case,” but I think that he knew I would find it because he counted on my looking. He apologized if I was hurting. His use of the word “if” was grating, as if there was any way I couldn’t be hurting. He said his favorite times were with me. The last five lines read:

You.

You made me a believer in love.

You made me believe.

You did that.

You.

Letter to John. (June 24, 2014)

On the morning of the one-year anniversary of John’s death, I wrote to him.

Hey John,

We haven’t spoken in a minute, I know. You’re certainly making up for that. This morning, I hear you everywhere. And I know there are things we still won’t talk about.

I workshopped an essay about you last week. My group critiquing it said they couldn’t see my love for you. They felt distance there. And they were right. It’s because I still feel shame for having loved you. You left me with a lot of shame, John. To be ashamed of good memories is a fucked up thing.

Anyway, it made me think well, how to do I revise this? What were the things that made me feel love for you? And I keep coming back to that morning we wrote together. You, working on that sci-fi novel. Me, on a short story. That morning, I looked over at you and thought this could be a lot of Sunday mornings. Our equivalent of reading the Sunday Times or going to farmer’s markets or whatever couples do on Sundays. It was symbiotic. It wasn’t that aficiamiento where you’re half-crazed over someone, and I think you knew that. It was the sense of partnership, of working, creating, side by side. Harmony. That’s what I didn’t say in my essay. That this part was so stellar that I was more than willing to work with the more jodon parts of you. Yes, jodon.

People ask me if I think we’d still be together. I always say no, without missing a beat. I don’t know whose benefit that is for. I say the critical, unbending parts of you would’ve swelled like a supernova to overshadow everything.

You know, eventually, I don’t want to remember this date. You, of course, I’d like to remember random things and laugh, but this date, no. I won’t mark it forever so maybe I will talk to you next year. Maybe I won’t. In any case, I’ll see you around, John.

-G

Last letter to JR. (September 2014)

I intended to write to JR because I was working on this essay. I didn’t. It’s been about a year since I’ve written to him. I know that the last time was after John died because I have a letter from him that says, “I won’t lie, I’m glad you’re still single but I’m very sorry about your friend.” I didn’t see the point of getting into details.

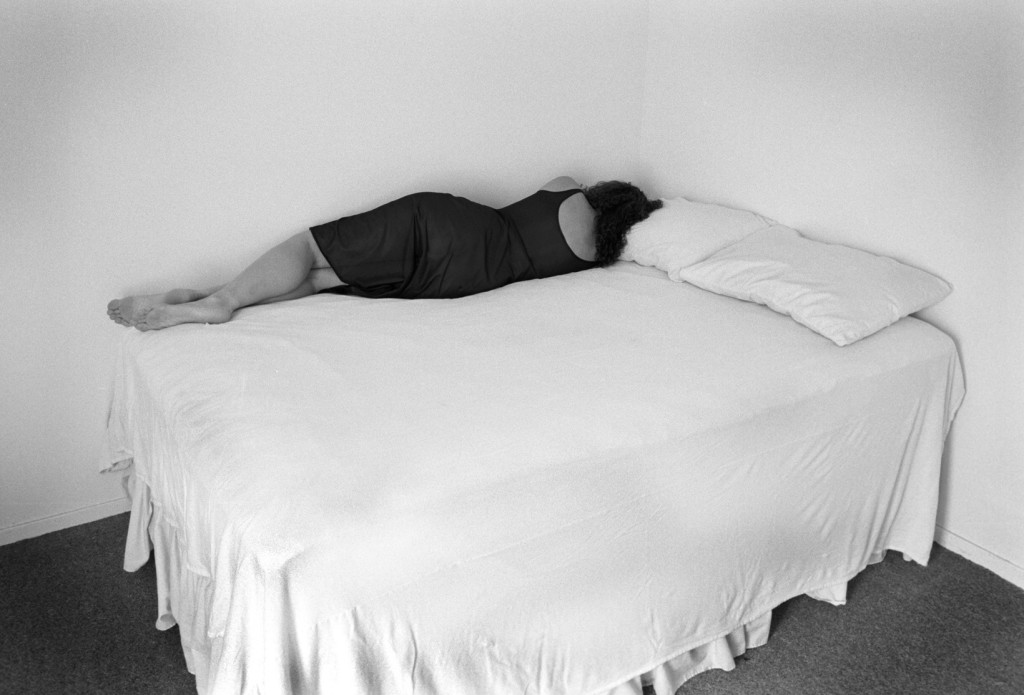

I save his letters, the first ones still bound with white ribbon as if I would be able to keep everything that neat for the duration of JR’s incarceration. The ones that came after, the ones I had time to read, but never got around to answering, are piled haphazardly on top. Maybe I’ll still receive the sporadic letter from JR, but one day the letters will stop completely because he will be home, a twenty-eight-year-old man who may not see love, or perhaps me, in the same fortuitous light as before.

I used to wonder if JR grasped the nuance between the terms “luck” and “blessing” when I reread his letters, but it was I that had been using them interchangeably, like shrimp and crab in the same chowder, close enough that I couldn’t be bothered to distinguish between them. Blessings elicit gratitude because of their benefit, suggest having taken action to achieve or suffering to earn. Only good people are blessed. Luck, on the other hand is as transitory and undiscerning as love itself. A spin on a wheel. But lucky or unlucky, blessed or cursed, none of those words really seem to be a good fit for the magnitude or complexity of loving or being loved by JR or John. It was both and neither and all.

•••

Follow

Follow