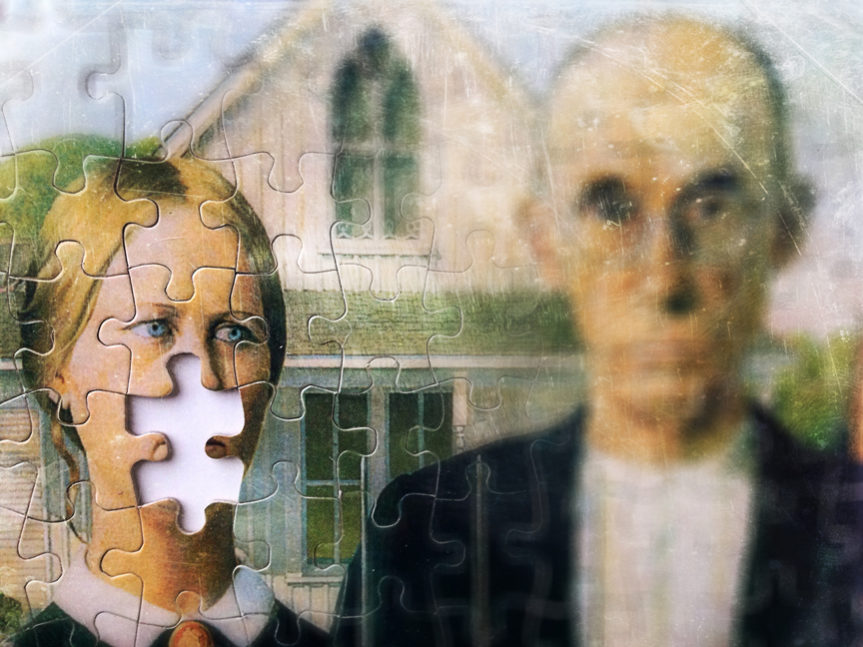

Photo by Gina Easley

By Magin LaSov Gregg

?

My body is being weird today. Hands tingling, forearms squishing. I stop typing for a moment and arc my arms in the air, a quick sun-salutation. The movement takes me back to a time I can barely remember, when I could squeeze in one yoga class per week between days of weight lifting and four-mile runs. That person I used to be glimmers like a ghost in my memory. Even when I squint hard, I can barely see her.

I haven’t run or practiced yoga consistently for years because my joints ache. Or the room spins like a Tilt-a-Whirl. Or everything in the distance looks like it’s melting. Today, thank goodness, there’s none of that. Just pins and needles in my hands and weakness in my arms. I can finish grading. I can teach my classes. I can get through the day. A few fingers on my left hand have started shaking. Stress, maybe?

When a friend walks by my office, I call for her to come inside. We’re work sisters, bonded by more synchronicities than I can count, including losing people we loved to the same illness when we were younger.

“Do your hands ever twitch while you’re grading?” I ask. I massage my right forearm. There’s a stabbing pain that started up two weeks after my flu shot. Now it feels like a needle straight to the bicep.

Work Sister slumps in a chair across from me. Every day we discuss my mysterious medical symptoms. Early waking. Anxiety. Insomnia. Vertigo. Nailed-to-the-bed exhaustion. What diseases do I have? Or is it all in my imagination? Symptoms, unattached to firm diagnoses, float like giant question marks over our heads.

“Maybe carpal tunnel?” she says, and I nod. I hope so. Something relatively simple. Something else to ask my new GP about when I see her next week.

Like me, Work Sister is tired this morning. She didn’t sleep well last night and might have a cold. As always, our fatigue comes at the worst time, at the tail end of our semester, when our grading load quadruples. She slinks toward her office and closes the door. If I need her, I can call. I don’t think I’ll need her today, but it’s nice to know she’s there, on the other side of the wall, like my own sister once was.

I go back to grading. My students are trying to make sense of Hillbilly Elegy, a book I find mildly irritating, but assigned because this year I’m trying to stop tuning out people I’ve written off. Like my father, who I was estranged from for eleven years. My father is from rust-belt Ohio, like the book’s author. And he voted for Trump, and I didn’t think I could ever understand this choice. But I’m trying. We’re talking more now. The last time, he did most of the speaking. He told me a story about his cat and then told me I worked too much.

Perhaps he is right. Is my arm-hand-shoulder malfunctioning the equivalent of tennis elbow for writing professors?

( )

My father and I have plans to talk tonight. I take his phone call in bed, even though it’s eight p.m. on a Friday. I worked a twelve-hour day, advising a student publication that almost didn’t make it to press. Now I cannot sit up. Also, my husband left this morning for a weeklong meditation retreat, and I am not feeling very Zen about his absence at the busiest time in my semester. Yet our ten-year marriage works because we hold space for each other and we make space for the other’s individuality. I’m more envious than resentful of his absence. I wish I could check out of real life, too.

Tonight it’s just me and a dog in the bed, and my father on the phone, talking about neutron bombs. He asks me about the basement bomb shelter we inherited from the previous owners. Have I gotten it repaired? How much canned food do I have down there? What about water? What is my plan?

“It will be every man for himself,” he tells me. This sentence comes after he has suggested I install a wooden wishing well over the manhole cover in my backyard, to hide my bomb shelter’s exit from marauding gangs. He will not be coming to save me. What else is new?

For a moment, I think of asking his opinion on Trump’s latest baiting of North Korea on Twitter. But I’m too tired to argue. I focus instead on the fallout in my body. I tell him a doctor has recently diagnosed me with shingles, but the rash and pain have since migrated, so it’s not that.

“I’m going to see a new doctor on Tuesday,” I say, leaving out that she’s a woman recommended by a friend who lives with chronic pain. My father still uses words like “hysterical” to describe my mother, dead now sixteen years from juvenile diabetes. I suspect he distrusts women in authority. I don’t tell him about what happened at the last appointment with my former GP, either.

(I left the former GP because he told me my shingles-ridden body was a threat to pregnant women. He went on and on about this until I stopped him. I didn’t tell him how his comment hurt me because I miscarried my first pregnancy and fell apart afterward. I didn’t tell him how I feared he believed my non-pregnant body was less valuable than a pregnant body. But I called the office the next day.)

“I won’t be needing a follow up appointment,” I told my GP’s receptionist. “I’m leaving this practice.”

Silence. And then, “We’re sorry to hear that.” Then, click. Why didn’t I speak up in the appointment or demand an apology from the doctor? Why was I satisfied with silence, a simple click?

The day I told my father about my miscarriage, he said, “Well, I have to go.”

I shook when I hung up the phone, and then walked fast out my front door, as if I could shake off his inexplicable apathy. But I called back the next day, too.

“I told you I had a miscarriage,” I said. “Why didn’t you respond?”

He claimed he hadn’t heard me, and I wondered if that was true. I wondered if me being real with him was too threatening, or if I was afraid he’d reject me each time I asserted my version of the truth.

Last year, when my husband and I joined the Women’s March on Washington, I told my father I’d be “out of pocket” that day. He never asked what I’d be doing, just like I never asked him if he actually voted for Trump. I simply assumed so because of the giant Trump sticker on the rear window of his car.

Out of pocket. My choice of words does not surprise me.

A thousand pockets line mine and my father’s conversations. Countless unvoiced words cram inside those pockets. They form sentences I’d stuff inside parentheses if I were writing everything out.

Parent, a root of parenthesis, means “to bring forth.”

Ironically, a parenthesis holds back. A parenthesis suggests sub-vocalization or even silence. At best, a parenthesis is the grammatical equivalent of muttering under one’s breath.

From the Greek para “beside” and tithenai “to put, to place,” parenthesis reminds me of another conversation my father and I had, when he was working the ninth step in AA.

He talked then about how he and my mother had separate roles in their marriage. He was the worker, the earner. She was the unpaid domestic. They “wrestled” because they did not agree on those roles. He used his fists, his buck knife, to put her into place. She almost died leaving him. But he still said they “wrestled.” His language made her a complicit partner in the violence he inflicted against her, as if they stood in a ring and shook hands after a coin flip. He towered over her, but he still insisted they had wrestled.

When my mother was dying, she begged me never to tell my father that she was sick. Her hands trembled when she said his name, although they hadn’t lived under the same roof for twenty years. Did she teach me how to hide a secret in the middle of a sentence? Did she write my first parenthesis?

Now, whenever I see the word “parenthesis,” I see the word “parent.” I see myself standing between them, like I did on the night of the buck knife, when as a toddler I pushed against him and said, “Stop.”

“ ”

A rash has erupted on my neck. It looks fungal, like ring worm. But also like acne. It wasn’t there when I woke up this morning. I notice red splotches spreading to my clavicle when I use the Ladies Room before class. I adjust a scarf Work Sister lent me when I texted her about the rash. I fix my lipstick, as if that matters.

The person looking back at me in the mirror is me and not me. Illness distances me from my body. I, or the person I used to think of as “I,” is no longer in charge. And I don’t know who has taken over.

Because I wear bright lipstick and dangly earrings and stylish clothes, I appear “healthy.” No one can see that my legs wobble as I walk. My calves have been tingling since Thanksgiving and are starting to numb. For the first time in my life, I’ve wondered if I might lose my ability to walk, but I tell no one of these suspicions. If I say them out loud, I’ll have to face them. Right now I prefer mystery, a sensibility I inherited from my mother.

When she and I were living into her last days, she liked to say, “It’s in God’s hands.” And she believed that. She believed in a mysterious force pulling the strings, choosing whether she’d live or die. She did not believe her suffering was a result of random chance or bad luck or biological determinism. Her God concept, I think, gave her hope and a sense of purpose. God relieved her of self-blame. I am glad she died hopeful.

A few years ago, when I went to Al-Anon once a week, we used to say, “Let go and let God.” Even though I didn’t believe in God anymore, I’d say these words with everyone else because I liked their rhythm, the way the right quote can ease anxiety, can feel like a prayer.

Back then, I was trying to understand the toll of my father’s addictions and abandonment. I wanted to believe in the possibility of okayness when everything was not okay at the moment. The closest I could come to believing in God was believing in hope, which lit a path toward okayness.

At the end of the Al Anon meeting, when we held hands and said The Lord’s Prayer, I choked on the first few words of the prayer: “Hallowed be thy name.” Sometimes a quote can hit like a punch.

The quote that gets me through my days comes from the New York City street artist, James de la Vega: “You are more powerful than you think.”

I have taped these words to my office computer. I say them quietly before class, as if I am trying to make myself remember something important. I try not to think about my father, who I’m fairly certain has never needed a mantra to remind himself of his physical power.

The “you” I am talking to is not the daughter who interrupted his fists years ago.

The “you” of my mantra is the “me” I used to be, the one who could trust her legs, the ghost glimmer of a self I hope to meet again. I wish I could welcome in my new self, this emerging sicker self. I want my words to make room for her in my body. I want to speak her into being, make her worthy, visible.

…

It’s a Sunday night, and I’ve spent the day grading. All I want to do is binge watch Christmas movies. But an unknown number flashes on my iPhone screen. A twitch in my gut tells me to answer the phone.

On the other end of the line, my new GP greets me. I saw her earlier in the week and agreed to more bloodwork. Now the tests have come back, she says.

Oh shit. My belly cramps hard. Doctors do not call on weekends with good news. Beside me, the dog shifts. I rub his belly, soothing him when I cannot soothe myself. My husband’s still away, meditating in the mountains.

“Your autoimmune tests are normal,” the doctor says. “You have Lyme disease.”

A pop releases from my jaw. I never saw a tick on me, never had the bull’s eye rash. Lyme disease? Is she sure?

The doctor assures me that my tests are conclusive and tells me I might be on antibiotics for a long while. I need to get over my fear of them, my assumption that they’re a modern scourge.

When my symptoms started a few years ago, my former GP tested me for Lyme. The tests showed some abnormalities, yet he dismissed them without suggesting follow-ups. I didn’t contest him. I wanted to be healthy, and he told me what I wanted to hear. My doctor was bigger than me, like my father. And a part of me suspects I didn’t challenge him because I still freeze up around large men with loud voices. I still wonder what menace lurks behind bravado. I shrink into silence. I defer.

Now the power of silence, of what is omitted, overwhelms me. Until it received a name, my illness was a silence whose form I could not trace, a deadly omission, an absence intent on destroying me.

My diagnosis punctuates that silence.

To punctuate means “to interrupt,” or “to mark,” or “to divide.” There was a healthy me, now there is a sick me. A before. An after. A self that is marked, not only on medical charts or insurance claims, but psychologically, emotionally. And yet, I am less sick now than before my diagnosis, which put me on the path toward recovery. Another mystery.

For my mother, diagnoses were question marks and exclamation points and, finally, periods, when she learned her transplanted kidney was rejecting seven years after the initial surgery and she would likely not have another organ transplant in time to save her.

My illness was an ellipsis for years, a disease hiding in plain sight, a disease with no words attached to it, no name, an ever-present absence.

__

For days after my diagnosis, I walk around imagining bacteria swimming through my blood stream. I picture sea monkeys dying, one by one, inside of me. Still on retreat, my husband texts me a photo of the metta prayer.

May I be happy. May I be well. I cannot complete the subsequent verses, the ones addressed to “you” and “sentient beings.” Borrellia bacteria colonized my body for at least two years, possibly longer. I will not bless a stealth infection that hides in my heart, my eyes, my nervous system.

I want my diagnosis to be a different form of punctuation –– a dash that forms a channel between the former and present me, allows me passage back to a healthier self who’s become a shadow, a ghost.

How many selves live inside of me? How many more will come? I used to live more than a thousand miles from my father. I once plotted a PhD in Renaissance literature and read Shakespeare for hours each day. When every doctoral program I applied to rejected me, my father sent me a box full of smaller boxes containing inspirational messages and trinkets. (I did not see the metaphor at the time.)

On one box, he taped an envelope with a poem inside. I’d spent months obsessing over variants of Hamlet’s soliloquy, the questions that form entry points in the play, all the dashes belying paralytic ambivalence. So the silly ABAB rhyme scheme poem by Linda Ellis, made me chuckle. Eight years later, I can’t remember more than the first five lines of Hamlet’s most quoted speech, but I can remember couplets from “The Dash.”

“For it matters not, how much we own, the cars … the house … the cash. / What matters is how we live and love and how we spend our dash.”

The academic in me wants to deride the poem’s platitudes, but I can’t. All those years ago, my father reached out to me. He tried to impart guidance, tried to teach me how love matters. I read this poem as evidence of his potential to be a father, and his longing to connect.

Maybe that’s why it’s so much harder when I stand in his kitchen one night and try to talk about my treatment, my fears of relapse.

He busies himself by spooning leftover Chinese food into Tupperware containers. His back stays turned, like a jammed door. He says nothing to comfort me. Again, it’s as if he hasn’t heard. In this moment, I am reminded of the dash’s double meaning, how a dash can connect –– and separate. On either side of his kitchen, my father and I form two ends of a dash.

He can only connect at a distance, and I cannot mediate all that divides us.

•••

MAGIN LASOV GREGG’s writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The Dallas Morning News, The Rumpus, The Manifest-Station, Literary Mama, Bellingham Review, Under The Gum Tree, Hippocampus Magazine, Pithead Chapel, Thread, and elsewhere. Proximity Magazine named her as a finalist in its inaugural 2016 Personal Essay Prize. She stopped making New Year’s resolutions in 2018, but swears she will soon finish her first memoir about marrying a Baptist minister while staying committed to her Jewish faith. She lives with her husband, the Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg, in Frederick, Maryland, where he now serves a Unitarian Universalist congregation.

Follow

Follow