By Randy Osborne

We had reached that routine-but-often-dramatic juncture in testimony when the victim is asked to point to his assailant and describe what the perpetrator is wearing.

It shouldn’t have been difficult.

Richard Ackerman—gaunt, pockmarked, in his mid-thirties—had finished telling how he was beaten and robbed by two men. One suspect had eluded police but today the other, a blond, sneering youth in a navy-blue jail jumpsuit, sat at the defense table with his lawyer. “He’s right there,” Ackerman said. “He’s got red hair and he’s wearing a black cape.”

On this slow courthouse afternoon in 1981, a nutty, disruptive event taking shape in what should have been an ordinary string-up for a standard-issue mugger could turn into column inches. Journalist me, in the public section, leaned forward. After a pause, the prosecutor sighed. Fists on hips, he regarded Ackerman: a problem. And a problem not for the first time in Rockford, Illinois.

“Let’s start over,” he said. “Can you point to the person who did this to you, and describe what he’s wearing?”

Ackerman’s deep-set eyes darted at three people in the benches with me: a young woman (probably the defendant’s girlfriend); a retiree picking his teeth with his fingernail (he was a courthouse regular); and me, in my red plaid shirt, sniffing out a possible story.

“There,” Ackerman decided. “He has brown hair and he’s wearing a red plaid shirt.”

I doubt Ackerman remembered me. More likely he panicked and, believing he had done the wrong thing, sought to fix his blooper—may it please the court —by the quickest available means. But I won’t forget Ackerman.

•••

Nine years old, summer, I trudge across the Whitman Street Bridge, aimed for the Burpee Museum of Natural History, where I will traipse the creaky floors—alone but for the stout curator, who checks me sideways—amid the stuffed birds and the glassed-in replicas of dinosaurs. Visit to visit, they stay the same, which pleases me and lets me down. A fatherless boy, I become an appreciator of artifacts.

I don’t notice Ackerman until he is beside me, and says hello.

A teenager with bombed-France acne scars, he wears an East High School jacket (cloth vest, fake leather arms) despite the heat. I’m already scared because of the bridge—height, water—and now this. His eerie solemnity and a slow manner, like a spider about to strike. Apropos of nothing he volunteers that he owns one hundred pairs of Levi’s jeans and sleeps at night in a coffin. Do I want to see the jeans, the coffin?

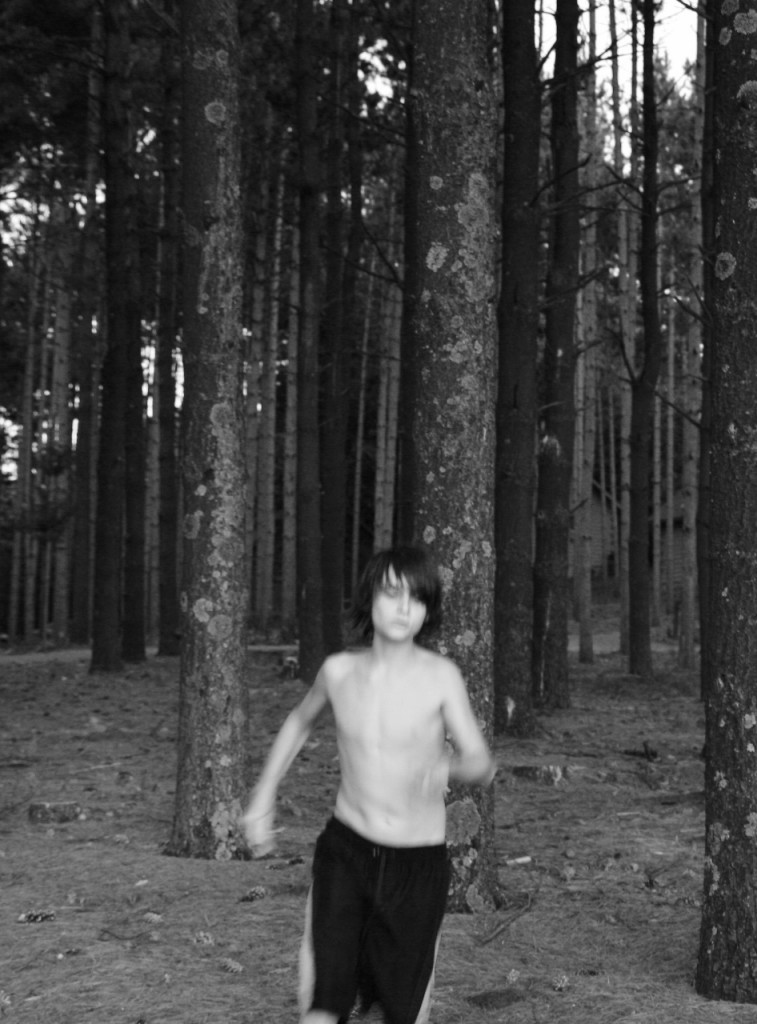

I run like a kid in flames.

In the following weeks, Ackerman pops everywhere in my neighborhood. The other boys, I discover, know all about him. “Has he showed you his dick yet?” Mickey Lindell wants to know. Everybody laughs. Ackerman, they say, is always talking about his denims and casket, and asking boys to visit his house. (Nobody does). And, at every opportunity, Ackerman is showing his dick.

Later I find out his first name and miss the pun. He terrifies me. All the grown men of our households have abandoned us—because of me, somehow, I believe. My father leaves my mother who sends me for raising to my grandmother, whose husband abandons her for another woman the year after I arrive. I am bad luck for grown-ups, goes my mantra, bad luck. Later, twice divorced, I will become bad luck for myself. But today this Ackerman apparently wants to be my big brother. When I tell my slightly-older-than-me uncle about Ackerman, he says, “I’ll bust his face!” but he’s laughing, too, and plainly useless.

Thanks to the ever-present jacket and his distinctive posture—rigid, soldier-like—I can spy Ackerman a block away, make detours. For the rest of my years in grade school, I manage to evade him. Other boys, I hear, are less fortunate.

My mother remarries and we relocate a few miles west of town. High school comes and goes. I suffer college briefly, and drop out for my first job in journalism, covering cops and courts.

Again, still, Richard is everywhere.

He keeps getting busted on misdemeanors—disorderly conduct and, of course, indecent exposure. At this point I’m equipped to see the humor in his escapades, which I chronicle for the newspaper with quiet glee. What an embarrassment to his family, Ackerman! Especially his older brother, a cop who ends up taking Richard into custody on his most serious offense, car burglary.

Officer Ackerman must have included in his narrative the make and model of the vehicle his brother pried into with the crowbar. Later I wished I’d had the sense to track this information down. Didn’t seem important at the time, but it would later.

•••

“There,” Richard said, and pointed at me in court. “He has brown hair and he’s wearing a red plaid shirt.”

The prosecutor shook his head, the judge grinned into the sleeve of his robe, and the public defender leaned back in his chair, half-smiling as if Ackerman’s horse had crossed the finish line first but would shortly be disqualified.

“Fifteen-minute recess,” the judge said.

The trial ended with a guilty verdict for Ackerman’s attacker. Over the years, Ackerman continually found for himself more low-grade trouble. Free on bail, Richard he misbehaved again.

He joined an open-casket funeral where he didn’t belong. Until someone singled out this odd stranger, Ackerman spent long minutes gazing at the body—almost meditatively, a mourner told me later. Officers had to drag him away. In another incident, Ackerman complimented the ass of a sign painter downtown, who didn’t see the humor, and gave chase. “You’re cute when you’re mad!” the fleet-footed Richard yelled over his shoulder, according to the police report. Repeatedly, incorrigibly, Richard showed his dick.

After the car burglary, the state made a move to revoke Ackerman’s probation and send Ackerman to prison for a while. (This clownish freak!) I flipped through the weighty file. A manila envelope slid into my lap: the pre-sentence report, a confidential document that clerks are instructed to remove before handing over any paperwork. Secret because it contains hearsay—interviews by officials with family, friends, and associates, material used by the judge to decide whether to give the probationer another chance or lock him up. I opened it.

Although, in my published account of the matter in re: Ackerman, I couldn’t quote from material that I was never supposed to see, but I’m at liberty to tell you here. Richard is beyond harm. He died in 1998.

His mother said in the report that Ackerman had not been normal since he was a lad—not since about the age I was when I met him, not since the day he tapped his pale father on the shoulder, shook him gently, and opened the car door wider to let the cold body fall sideways onto the garage floor. Tailpipe smoke must have floated around them, boy and man. His mother found him running in circles and screaming. The report does not disclose if the car is a Ford or Chevy or Oldsmobile. I wonder if things might match up.

Match up, like two images of him that persist for me. Ackerman in frantic motion, dizzy from the carbon monoxide and from whatever this loss had begun to mean for his soul, never fully known or understood, maybe, by him. Surely not by me.

And then Ackerman on the witness stand, trying to make right his wrong. His finger extends at me, the plaid-shirted one, an ill portent—the damned boy who makes the men run away. As if I am again and forever accused.

•••

RANDY OSBORNE’s work has appeared in many small literary magazines online and four print anthologies. It was nominated three times for the Pushcart Prize, as well as Best of the Net. One of his pieces is listed in the Notable section of Best American Essays 2015. He lives in Atlanta, where he is finishing a book. He’s a regular contributor to Full Grown People.

Follow

Follow