By Jennifer Niesslein

“That’s where they found her body.”

I nose the rented mini-van onto the side of the narrow road, and Gram and I get out. It’s a lovely little grassy patch that slopes down to a sun-dappled creek. Or crick, as we call it.

“She had one arm raised above her head,” Gram says, “like someone dragged her there.”

When I think of western Pennsylvania fondly, it’s summer that I’m remembering: the greens of the trees and grass, the bursts of neon yellow from lightning bugs, the red tomatoes from the garden up on the window sill. But PA in the winter is, frankly, depressing—the grim black-and-white tableau—with the black mountains, the stark white snow, the clumps of gray frozenness along the turnpike. It’s a place where the coal mines have made their mark, and slate piles still stand.

When she died, on January 22, 1932, it was cold and the forecast had called for rain. It’s likely her body was found soaked, her long skirts muddied and bloodied. I imagine the creek’s waters rising toward that arm.

•••

She’s my Gram’s grandmother, my great-great-grandmother. Growing up, I only knew three things about her: The legend was that her husband, a coal-miner like so many Polish immigrants, was in “frail health,” and as a result, she took up bootlegging—and was successful enough at it to own three houses. Her fourth child, her youngest, was rumored to be of mixed race. And she was murdered.

How could I resist mythologizing her? On these barest of bones, I pressed on flesh that reflected the fantasy of who I’d be if my back were to the wall. A bad-ass! A proto-feminist! An outlaw! A woman who landed on her feet when times got tough! Myths, of course, always represent the imagination of the myth-maker. I didn’t even know her first name or what she looked like, but I was eager to find a woman in my lineage who didn’t play by the sometimes arbitrary rules.

Mom told me that Gram didn’t like to talk about her, so when I was a kid, I didn’t dare broach the subject. She was a warm grandmother and doted on us, asking my sisters and me to sing songs on their breezy porch, teaching us Scrabble and Boggle, and rewarding us with small gifts. But there were unspoken rules to be followed, enforced by the time-honored code of passive aggression. We—especially as girls—were to appear “neat” (for some reason, that was and is a massive compliment in Gram’s eyes), not bicker, attend church regularly, and excel in school. Gram didn’t smoke or drink or swear. The most outrageous thing she did on a regular basis was to wiggle out of her bra while driving, twirl it on her index finger, then fling it onto the backseat of her Cadillac.

Sometime in my twenties, Gram and I became friends. She’d somewhat loosened up by then; she’d occasionally have a glass of pink wine when her son-in-law encouraged her, and she let my boyfriend and me sleep in the same bed when we visited. When I became a mother, we grew closer, swapping tales of motherhood, then and now. (If only for the accessibility of washing machines, now is better.) In recalling the hard times, Gram reverts to the second person.

In my thirties, I felt close enough to Gram the person to ask directly about her grandmother. What happened? We talked, and over the course of several years, I pieced together the memories and legends with possibly the only person alive who actually knew her.

I told Gram I’d do some research. “Be careful,” she warned me. “There are some people in the family you don’t want to talk to.”

This was code. Not every relative had become respectable.

•••

When someone is a myth, it’s easy to forget that she was also a person.

Her name was Anna Dec Fisher. She and my great-great grandfather John emigrated from Poland. Her first name was sometimes “Annie” and their last name wasn’t really Fisher. According to census records, their true last name might have been Ezoeske, Jezorski, or Yozarski. They spoke Polish, and a few fragments of their language still run in my family. “Zamknij się” means “Shut your mouth.” “Jest zimno” means “It’s cold.” We, the descendants, have bastardized the foreign phrases to accommodate our American tongues.

Annie and John immigrated in 1901, a time when the United States was still figuring out how to sort the new waves of immigrants into the racial categories it had constructed. Poles were technically white, placing them above some races, but not the right kind of white. Or maybe the right kind for certain interests. Bluntly put, Poles were considered by mainstream America as strong and hard-working—the perfect fit for manual labor—but stupid. Ralph Waldo Emerson, approvingly, wrote in 1852, “Our idea, certainly, of Poles & Hungarians is little better than of horses recently humanized.” (Oh, Ralphie, go shoot your eye out.) A U.S. Steel Corporation want ad from 1909 read, in part, “Syrians, Poles, and Romanians preferred.”

Annie wasn’t stupid. She was just new. It’s unclear if she and John landed in U.S. together, but they came from different parts of what was Poland. (Poland didn’t technically exist as a country in 1901.) John was from Galacia, the poorest region of Europe at the time, then in Austria-Poland. Annie claimed Russia-Poland. They started off their new lives together in Ohio, where their first child, Mary, was born, followed by Helen (my great-grandmother, Gram’s mom), and Walter. By 1910, they were in Walkertown, a small town in West Pike Run Township, Pennsylvania. John worked as a coal miner. It’s where their last child, Adam, would be born.

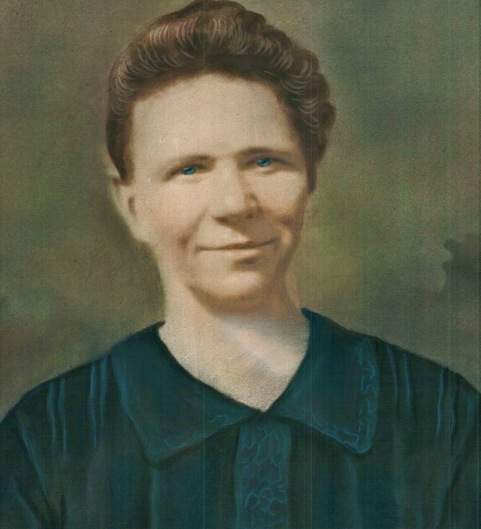

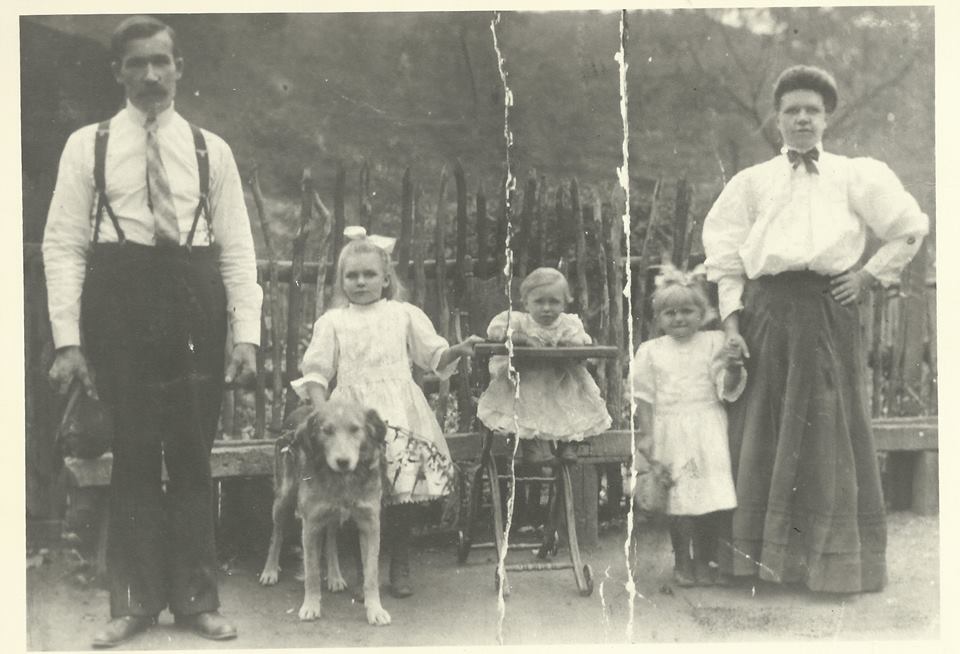

The first time I saw of picture of Annie was in an old photo that my distant cousin Nicole shared with me. (She’s Walter’s granddaughter.) It’s a family photo from before Adam was born. Annie is standing, one hand on her hip, the other holding Helen’s hand. Her hair’s styled in one of those froufy buns popular around the turn of the century. She wears a bow-tie in her puffy white shirt with a full-length skirt.

By the April 1920 census, they already owned their own home, free of a mortgage. In January that year, the government had enacted the eighteenth amendment, also known as Prohibition. At some point, Annie and John started breaking the new law.

I started finding more artifacts, and the myth of Annie started breaking down. A different picture of her emerged from the bath of historical documents and the context of her life. And that picture of Annie’s life and how she spent it would haunt my family all the way down to my own upraising.

“My dad said everyone did it,” Mom told me, referring to the Prohibition-era law.

“Yes,” I said. “But not everyone went to jail for it.”

•••

Walkertown was small, and people talked. Adam was born in 1916 and was not yet five at the time of the 1920 census. The census-taker seemed to be confused. In the column for race, a Mu for mulatto is marked, then written over more strongly with a W for white.

It wasn’t just the census taker. There seemed to have been a non-governmental consensus that John wasn’t Adam’s father. Gram told me that when she was a kid, sometimes she’d go to the movie theater where Adam worked. He’d let her in for free. But neither would get too close because, you know, the rumors. Later, Adam would leave Walkertown, marry a white redhead, and join the military. Outside of Walkertown, as far as I know, no one questioned his whiteness.

Nicole is also the one who first showed me pictures of Adam. He was a handsome guy, although slightly darker than the other Fisher siblings. This doesn’t mean a lot to me; I have an uncle with a darker skin tone than his siblings, too. Genes pop up in the most peculiar ways.

This interracial brouhaha is so unremarkable now that I feel ridiculous bringing it up, but then I remember that sometimes my grandparents would explain their youths to me in ways that could only be seen as racist. Dating an Italian was almost as bad as dating a black. Meaning, in the poor white community, you lost status. You lost your advantage, which was the measure of respect that your skin color afforded you. The only thing that kept you from being at the very bottom of the American pecking order. Even the rumor of blackness was enough to awaken the racism of Walkertown.

I wonder sometimes if the people of Walkertown would have even questioned Adam’s race had there not been a man, labeled by the census as mulatto, living next door to Annie and John. Short of finding Adam’s descendants and convincing them to give me a quarter teaspoonful of their spit to send to an online DNA profiler, I’m not going to know. I don’t need to know; we’re judged on how we present, not who we are, anyway. Annie could well have had an affair with the guy next door. But she just as easily—more easily, actually—been friendly to her next-door neighbor. Or, easier still, she could have done nothing at all.

All the rumors mean is that Annie was the kind of woman that her white peers thought capable of crossing the line between proper and improper. Whether Adam was John’s son or not, they were right. Annie was woman who crossed lines.

•••

By the summer of 1929, if Annie hadn’t earned respect through piety and birthright, she was grabbing it in the real American way: money.

Two of Annie’s children had married and had had children of their own. According to the family, Annie owned three houses by then. Her oldest, Mary, lived with her family in one. Helen lived with her family in the multi-unit house next to Annie, John, Walter, and Adam.

Annie was bootlegging. She was good at it. I believe she was the brains of the couple, able to read and write while John couldn’t. Gram remembers the yard filled with cars. She was young, just five when her grandmother died, too young to understand that these were probably the cars of paying customers visiting her grandparents.

On July 29, 1929, police raided Annie and John’s house. According to police reports, Helen yelled, “Beat it! The law is coming!”

I imagine customers scrambled into those parked cars and beat it with a quickness.

Next, Helen dumped out a pitcher of liquor that was on the back porch and told the cops, “Go ahead and search. The evidence is gone.”

The evidence wasn’t gone. They found sixteen quarts of beer, two barrels of wine, and a quarter gallon of moonshine in a gallon jug.

Annie, John, and Helen were arrested.

•••

I questioned the documents that I received from Washington County. Did the woman I knew as Grandma Crawford, the permed lady with the puffy pink toilet seat and yappy dog named Duchess, really call out, “Beat it!”?

But then I remember how notoriously blunt and mouthy she was. When I was a kid, she accused me of cheating at 500 Rum and made me cry. When her daughter-in-law and her son-in-law left her children for each other, her remark was, “Why would he leave one fat one”—her daughter—“for another fat one?” When my parents separated, she cut to the chase—no I’m sorry, honey—and offered Mom money if she could live with us. (We didn’t have anywhere to put her.)

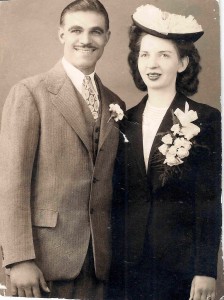

And looking at photos of her when she was a teenager, with her bobbed hair and defiant face, I could believe it.

But I also believe that the arrest changed something in Helen.

The next morning, John was charged with manufacturing and possession. Annie and Helen were charged with sale and possession. The bail was $1000 for Annie, and $500 each for John and Helen. None of them could make bail, so they sat in the Washington County jail.

They sat there for a while.

(This was news to Gram. When I told her, she immediately asked, “Where was I?”

She would have been not quite three years old when the arrest happened. My breath caught, realizing that this isn’t some historical curiosity, that I can’t stand on my middle-class perch and think that my research doesn’t have real-life ramifications, just as current-day journalism doesn’t have ramifications for the subjects, especially ones whose names show up in the crime section, not the society section, of the newspaper. My voice softened. “Your dad’s mom Amanda lived with you then, Gram. I bet she took good care of you.”)

On August 21, 1929, the testimonies of the law enforcement officers were entered into the record. On September 9, 1929, John, Annie, and Helen went before a judge. John and Annie pled guilty at some point—perhaps that day—but Helen did not. On October 1, 1929, the district attorney filed a motion with the court for a nolle prosequi (meaning that the state acknowledges it doesn’t have enough evidence against the defendant to prosecute) for Helen. He noted that Helen’s parents were now serving their sentences. I don’t know what those sentences were, but they’ve become irrelevant in the story of my family. I spoke to a friend with a legal degree, and she suspected that Annie and John’s plea deal included the stipulation that Helen go home. She’d already been in jail for over two months.

Helen had missed Gram’s third birthday during her time there; her son was five years old, her second daughter, just an infant. Her breasts must have ached terribly, lumpy and swollen with milk. I think of her there, now a twenty-three-year-old married mother, in an iron and steel facility once called “a modern day Bastille.” I can’t imagine the shame that must have plagued her, the dignity robbed. I can imagine, though, that the experience strengthened her already-entrenched resolve: Become respectable.

•••

I was well into adulthood before I heard of respectability politics, and I only learned of them in the context of African-American history. In a nutshell, it means when a group outside of the mainstream tries to assimilate in order to become accepted. The opposite is when a group outside of the mainstream fights against what the mainstream insists is The Right Way of Living.

In terms of race, only white people can win the respectability game because we don’t carry any visible markers that we’re different. We can dress like the respected people; we can adopt their mannerisms, their biases, their way of speaking.

We can, but not all of us do. The people who don’t are the people who Gram spoke of, the ones I shouldn’t want to know, like the relatives who came to my grandfather’s viewing and were caught rifling through the pockets of the mourners’ coats. As now-respectable white people, we don’t know what to do with them, even as we know their personal histories and how much they’d have to overcome to have a shot at mainstream lives. They’re not the rebels we mythologize. They’re problems to be avoided because they’ve proven they will fuck us over in real time.

•••

I see our family’s striving for respectability in an artifact. There’s a photo of John and two friends, the Novak brothers*, in my grandmother’s box of old photos. Written on the photo is, “The Drunks.” I recognize the handwriting. I’ve seen it once a year for half of my life on birthday cards that arrived with a five-dollar bill tucked inside and signed “Love, Great Grandma Crawford.”

•••

Actually, I don’t know for sure if the Novaks were Annie and John’s friends. They seemed to have been, although God knows I’ve taken drunken photos with people who were little more than acquaintances.

On the year Annie would turn fifty-two years old, though, she went over to help Pete and Agnes Novak render lard from a recently slaughtered pig. One version of the story has her doing it out of the goodness of her heart and maybe some portion of the lard. Another version has her working as hired help. In any case, by that time, John wasn’t working; his lungs were severely compromised due to his time in the mines.

Annie didn’t come home the night of January 22, 1932. Her body was found by the creek the next morning.

•••

I came to the story of Annie originally believing that I could Nancy Drew this sucker open and find out what really happened. Was she murdered? Was it some sort of cover-up? Were the Novaks ever implicated?

What I found out was that I’m so far removed from the underclass—by my own foremothers’ design—that I took for granted that her suspicious death would warrant the kind of investigation that mine would.

On January 25, 1932, Annie made the news in a non-criminal way for the first time. The Charleroi Mail (a newspaper from a town not far away) reported the headline, “Find Lifeless Body of Woman on Road; Heart Attack Victim”:

The lifeless body of Mrs. Anna Fisher, 52, of Walkertown, was discovered yesterday morning by John Hans, lying beside the road between Walkertown and Daisytown, near California [Pennsylvania].

Deputy Coroner J.F. Timko, of California, stated that the woman had been dead about twelve hours when discovered. Mrs. Fisher had left the home of Pete [Novak] for her own home shortly after dark Friday evening. Members of her family were not alarmed over her absence because her husband was away from home. Death was due to a heart attack.

She leaves her husband John Fisher, and four children: Walker and Andrew Fisher, at home, and Mrs. Helen Crawford and Mrs. Mary Smolley, both of Walkertown.

This wasn’t journalism’s finest moment. They got the date wrong, the spot wrong, and Walter’s and Adam’s names wrong. They probably even got her cause of death wrong.

Her death certificate lists her cause of death as “acute gastritis and enteritis” and states her death occurred around eleven at night.

Believing that the Novaks were her friends, I formed a story in my head in which Annie, who was likely a pretty hearty drinker, went to help the Novaks with the pig. While she was there, she died of natural causes. The Novaks—who didn’t have such a clean record with law enforcement themselves, both with arrest records on alcohol-related charges—panicked and put her body by the creek.

I messaged Nicole about it, and she wasn’t buying it.

“Did they do an autopsy?” she asked me.

I looked at the paper in front of me. “It’s blank. So I guess not.”

“Then how do they know?”

“Good point.”

Later, with the help of a friend with medical knowledge, I looked into whether one can die of gastritis and enteritis. Turns out, people have actually died of it—but the real cause of death is dehydration as a result of prolonged vomiting and diarrhea. It certainly doesn’t seem like something that would cause you to keel over while walking home after rendering lard.

Nicole was right. We’re never going to know.

•••

When Gram and I visited, all of Annie’s houses were still standing, although the movie theater wasn’t there anymore and the general store was boarded up. Gram’s knees were bothering her, but I held her hand—so much like mine, long-fingered and slim—and we made our way to Mary’s former house where a picture of Gram was taken so many years ago. That solemn, round face, those straight bangs and pageboy haircut. We knocked, but no one answered.

Annie’s house was now painted a mustard yellow. Gram’s childhood home was still white. As we stood there, a woman came out of one of its units. She didn’t know any of the history, and besides, she was on her way to second shift.

After Annie died, the story goes that Mary didn’t pay the taxes on the houses (why she was the one in charge, I have no idea), and that they were taken by the government. Helen’s family wound up in Daisytown, around the bend, in company housing.

We stopped there, too, but we didn’t get out. I have no poker face, and I didn’t cover how appalled I was fast enough. I think my expression showed the gulf between my life and hers. The houses were exactly as Gram had described them: one room that was the kitchen and everything else, two smaller rooms that served as bedrooms, no matter how many children your family had. The reality—the poverty—of it didn’t hit me until then. People still lived there. “That one was ours,” Gram said. “At least we had an end one.”

“I used to visit my grandfather when I was a kid,” she said later. “We’d walk from Daisytown to Walkertown.” I told her that the census reported that he didn’t speak English, only Polish. She laughed. “He spoke English. I remember him as kind. He was gentle with us. He and Adam lived in a house that was half-burned down, but he loved when we visited him.”

•••

With Annie transformed from a myth into a woman, I’ve had to face the myths that I built about myself.

When I was a kid, my family went though a serious rough patch, and it made a mark on me. Even before the steel industry imploded, we weren’t financially stable, but once my dad got laid off, we were forced, for a time, to go on food stamps. I ate government cheese. We relocated to a different state and eventually gave our Pennsylvania home back to the bank. Those aren’t the things that made the mark. It was the knowledge, even then, of the difference between someone’s compassion for us and someone’s pity—which is somehow worse than scorn. You can meet scorn with scorn; you can only meet pity with shame.

It’s been more than three decades since I’ve been in that place, but I still think of myself as the underdog. I’m not. My own descendants—including my son, who (despite my fears) did not become an entitled little shit—will find that I’m a relatively rich woman, and any problems I’ve had with respectability are only visible if you know what to look for. But I’ve clung to the underdog myth because part of me believes that I’d be incapable of showing compassion—not condescending pity, not scorn—to marginalized people if I hadn’t, on some level, experienced it myself. I still grapple with the idea that compassion springs from who you are, not who you come from.

Try as I might, I can’t let go of my own myth. Go ahead and search. The evidence isn’t gone. It’s just trace amounts at this point.

•••

JENNIFER NIESSLEIN is the founder and editor of Full Grown People. She’s changed the “Novak” family’s name out of respect for their descendants.

Follow

Follow