By Laura Giovanelli

On our fridge, there’s a pair of grainy black-and-white ultrasound stills, held up with a small plastic duck magnet and looking back at me and my husband every time we open the door for half-and-half or orange juice. In the photographs, our baby looks like a fuzzy cashew. A lima bean. A smudge on a window you could wipe away with Windex and a rag. It’s hard to believe this is where we all begin.

You may be daydreaming about having a boy or a girl, but the external genitals haven’t developed enough to reveal your baby’s sex. (Try our Chinese gender predictor for an early guess!) Either way, your baby—about the size of a kidney bean—is constantly moving and shifting, though you still can’t feel it.

I am going to be a mother, and all I can think about is my father.

My dad and I haven’t talked in nine years. But I’m the one it seems to bother. Closer to a decade than not. No phone calls, but also no letters, no emails, no texts. Not that I can imagine my dad—or the practical, literal, somewhat-adverse-to-technology engineer who was the father I used to know—texting. When I was a teenager, he was morally opposed to call waiting; in my early twenties, I alarmed him with my fumbles at blogging. I’m not alone in this—my parents had three daughters, and my younger sisters don’t have contact with our father either. It’s been so long since we’ve last talked that I have to stop and count, skip back like I’m flipping through a photo album in reverse, tallying up the times we missed. Graduations. Christmases. Birthdays. Father’s Days I avoid thinking about by giving the card section at Target plenty of distance starting right after Memorial Day.

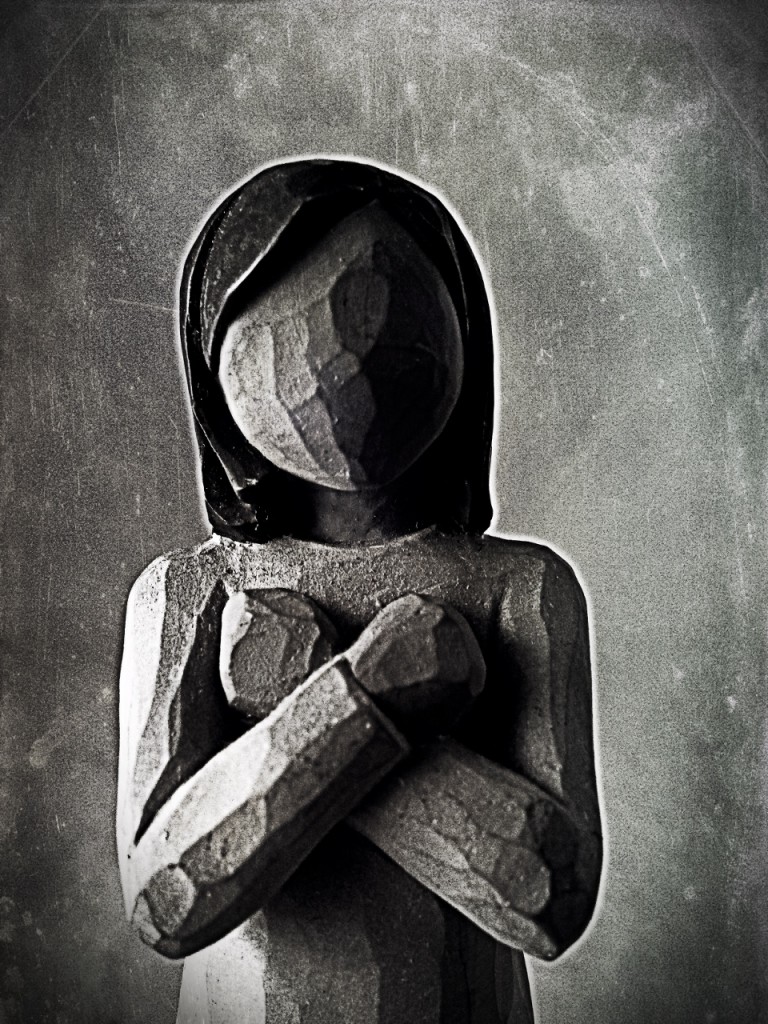

It is surprisingly easy as an adult to go through everyday life not talking about the person who contributed half of your genetic makeup. When other people talk about their fathers, I smile or nod and hope the conversation moves on to weather. Or I talk about my father-in-law, or I cast my mind back to some time when my dad and I were talking, the more distant and innocuous memories papering over more recent unpleasantness. It’s as if I have one half of a family tree and simply painted over the other side. As if I’m walking around tilted, weighed down by one branch heavy and rich with boughs and leaves and fruit, and on the other, there’s nothing but air.

•••

There are some big no-no’s when it comes to activities for expecting moms. Some of them are pretty obvious—no bumper cars, no new tattoos, no hot tubs—but others may surprise you.

I tell my mother I’m leaning toward sending my dad a letter. I have specific reasons. A letter is quieter. It does not demand but asks. Informs but does not interrupt.

And then, of course, I make excuses not to write it—I’m busy with grading, with talking to my students about their writing, with planning a friend’s wedding shower. In early March, I wake up, and before I can change my mind, I write to him, still in my pajamas, standing up in my kitchen, early spring light bathing the wooden countertops as I blow toast crumbs off the page. What I have to say is short and straightforward, more of a note, really, scrawled on a bright green handmade paper card from a long ago Christmas stocking. The paper feels fibery, alive, like skin; I think this card will be good luck. This feels like a special occasion, the right time to use it, but I have to use two because I ruin the first by splashing tears onto the ink.

I tell my father if all goes well, he will have a granddaughter around Labor Day. Maybe I make a bad joke about planning my pregnancy that way, evidence of a nervous tick I can’t seem to avoid even when I have the chance to edit it out. I write that I am thinking of him. That I don’t expect anything in return.

But the truth, of course, is I do expect something. I can’t not expect something even as I try to let him go. The letter itself is an extension of a hand, even if it is hesitating and trembling and uncertain. In that small envelope, I have sent part of my heart.

•••

Your pregnancy: 15 weeks! Your growing baby now measures about 4 inches long, crown to rump, and weighs in at about 2 1/2 ounces (about the size of an apple)…although her eyelids are still fused shut, she can sense light. If you shine a flashlight at your tummy, for instance, she’s likely to move away from the beam.

Each Monday, cheery pregnancy email newsletters arrive in my email inbox comparing our baby’s growth to something edible: this week your baby is the size of a kumquat, the size of a mango, of a rutabaga, of an ear of corn. One week, my husband will receive a digital bulletin comparing our growing child to a pot roast. I’ll get an eggplant.

Included in these newsletters is no advice on how to talk to your estranged father.

My father and I stopped talking for reasons that now make us both look foolish. Maybe we have that in common. Perhaps I can stash this away in the basket of traits I’ve inherited from him: overly thick and unruly dark hair! hazel eyes! stubbornness and the inability to admit we’ve been wrong about something!

I’m sure, too, he has his own version of events, but here is how I remember it. Nine years ago, my youngest sister was graduating high school. To celebrate, my mother’s family planned a party. What my father said after he was invited: he was just there for the ceremony, flying down from New Jersey for that and only that. What he didn’t say: he had done the calculus, the return-on-investment, and the three children from his first marriage were not on the winning end. I remember pleading with him outside the newspaper where I worked at the time, my face hot and sweaty from being pressed to my cell phone. I paced up and down between hydrangea bushes, attempting to appeal to his most logical side, what rhetoricians, or people who study language and communication call logos, as in logos = a waste of time and money to fly five hundred miles only to sit in a hotel room. And then, because this was always a second and often less successful tactic with my dad, I attempted to appeal to his emotions (pathos = come on, it’s his daughter, my sister, we’re talking about here). He was unmovable as a boulder, which made me a foaming, irrational kind of furious. He grew calmer. I grew angrier. Mistakes were made, as they say. He cancelled plans to come at all. Maybe he mailed me a card, maybe followed up with phone call or two—all of this is lost in the fog of anger and hurt I was determined to wallow in—and after that we settled into a firm standoff of silence.

Here’s an addendum. The way my husband recalls it, I was also trying to persuade my dad to stay a few days longer. I was proud of the life we were building: the old bungalow we were renovating, our careers, our promise. We had 401(k)s! We had health insurance! What more can you ask of your adult children, especially if you happen to be into logic? He declined. He had to get back for Father’s Day, he said, to spend the day with my two younger half siblings.

Even now, right now, when I Google these dates and re-Google them, I’m shaking my head thinking, no, no, memory, you have it wrong. Memory may be slippery but a calendar isn’t. In 2008, my sister’s high school graduation ceremonies were on June 14. Father’s Day was the day after.

•••

Your pregnancy: 16 weeks! Get ready for a growth spurt. In the next few weeks, your baby will double his weight and add inches to his length. Right now, he’s about the size of an avocado: 4 1/2 inches long (head to rump) and 3 1/2 ounces. He’s even started growing toenails.

The pregnancy newsletters are silent, too, on when you will know you’re bonded with your unborn child. Will it be when they are the size of a turnip? Of a butternut squash?

Early in my pregnancy, I hope I wake one day and find my instinct to be a parent waiting for me beside my bed with my glasses. Instead it feels as if I’m walking around with a low-grade flu for two or three months. It’s a malaise that spreads to my head and my heart. My body changes but not in a way that delights me; most mornings, it’s time for another nail biting game of “what clothes will fit me today?” The first and only time I enter a maternity store, I ease around racks of tee-shirts declaring in chubby script “Happiness is On the Way” implying that, at least to the wearer, happiness had never existed before and indeed could not without the prospect of becoming a biological parent. “It’s a miracle,” a friend says of my pregnancy. I shrug. Isn’t it just nature?

Science assures me indifference is normal. According to anthropologist Meredith F. Small, prenatal bonding usually happens during the second trimester. This is when mothers begin to feel their babies move; the moving it seems, makes things more real. The attachment changes with experience, too. In one study, women who have given birth and raised a child for one year felt a stronger bond with their offspring than when they were still pregnant. And this attachment isn’t solely a matter of sharing a body. It leaves room for fathers and non-biological parents to bond with their children because they want to, not because they have to. Logically, this all makes sense. Still, I study the grainy image of the cashew on the fridge and try to name what I’m feeling, testing it like it is a twisted ankle. Is it love yet? Now? Now?

What is messy and confusing about with my relationship with my father is that there is so much good I can’t wipe from my hard drive. It isn’t possible for me to just pack these childhood memories away, like old books or toys or faded clothes that really should be taken down to the Salvation Army for a donation. I replay them even when I don’t want to: the tree house he outfitted with a crate and pulley system so I could haul up my books and less compliant passengers, such as my cats; the handle he engineered out of duct tape and cardboard so I could carry cupcakes to school without squishing them; the eight-foot tall bookshelf he designed and built me after college. The nights when I had a stomach bug and he sat with me on the bathroom floor, holding back my hair as I wrapped my arms around the cool, slick sides of the toilet bowl. The wide-mouthed Cheshire cat faces he sketched in red marker on paper bags when he packed my lunch, or the songs he made up to sing to me when I had nightmares. The time, more than a year after I graduated college and should have been better able to take care of myself, when I called him from the side of a Pennsylvania interstate because my ten-year-old Nissan Sentra’s alternator had given out and I had no idea how I was going to pay for the towing let alone the cost of repairs.

Perhaps we all keep a running tally of how the people we love the most hurt us. And our parents, because they often are our flesh and bone and blood and the first humans we know, they are the ones destined to be at the top of that list. A plus in the black here for something that makes us feel loved. A row of red minuses for the things that really tick us off. Are we ever really even? When do we understand our parents as people?

•••

Your pregnancy: 20 weeks! Your baby weighs about 10 1/2 ounces now. He’s also around 6 1/2 inches long from head to bottom and about 10 inches from head to heel—about the length of a small banana. You’ve made it to the halfway mark in your pregnancy, so celebrate with a little indulgence. Need some ideas? Try a new nightgown or pajamas, a prenatal massage, professional pictures of your pregnant self, a beautiful frame for your baby’s first picture after birth, or a piece of clothing that makes you feel really good.

For years, I thought a letter was the key to crack the silence. It was all I needed to pick this lock: a handful of magic words, a password, just like in a fairy tale. But now that I’ve sent it and it’s gone and nothing comes back, a letter also gives me license to imagine what could have been and what might have happened. What if it got lost? I wonder if I should email instead. I wonder if I even still have his email address, if he is even still working where he worked eight years ago, if he is working at all, because he could be retired. What are other ways of reaching out to your estranged father? Hallmark doesn’t make cards for this. I weigh the emotional pull of an ultrasound, the possibility of a birth announcement. “Should I send another letter?” I ask my husband. “What about certified mail?” I’m not even sure how certified mail works; will he have to go to a post office to sign for it? It seems aggressive, to send a letter that way. Demanding to be read, or least to be seen. The certainty appeals to me, though. How else do I know he knows?

What I did not write my father: I didn’t tell him it took me a long time to get pregnant, longer than I thought I should have to wait, as if becoming a parent was my right. At first, we told ourselves all the things other people were telling us: to be patient, to not worry, which, as the anxious among us know, worrying about worrying is really the most futile game a human can play with their mind. After two years, we began to see doctors. I didn’t tell my father I tried to see my life without being a mother even as we were so bent on having a child we were on the verge of starting in vitro fertilization. And we knew—we didn’t talk about this much but we knew—once we opened that box we would keep throwing money we didn’t have into it, as bottomless as it might be.

I didn’t tell my father, either, how friend after friend gave birth to one kid, then another, in the time we were trying for just a first. The few I knew were struggling, I avoided like they had a disease I could catch. How, when I heard one couple was starting IVF with an egg donor, I scoffed out loud it was going too far but inside, I was envious of their choices. I didn’t tell him what it was like to be jealous of your friends’ miscarriages, because, if you miscarried, at least you knew you could conceive. I didn’t tell him how I stopped going to baby showers. How I laid on the crackly, tight paper of an exam table at my infertility doctor’s office gazing at a poster of a Caribbean beach taped to the ceiling. There, I waited three separate times for a nurse to insert a catheter loaded with my husband’s sperm and three separate times it was in vain even though the sperm and the egg were right there, we were setting them up on a date and pulling out all the stops, a view of sugar white sands and palm trees and everything, so how could this not happen?

I didn’t tell him how infertility tests showed nothing wrong. How, for me and my husband, trying to make something together began to feel like it was cracking us apart. How we blamed each other and then when we were tired with that, we turned back to blaming ourselves. How phantoms hovered over our bed as we tried, again and again, to bend our bodies to our will and create the image of a family fixed in our heads.

How when I missed my period just after Christmas, I took five pregnancy tests over a week, so uncertain I was by then that my body could even do this.

If I could say something to my dad now it would be that I’m lingering in the doorway of parenthood, peering down the hall and trying to see down its dimly lit walls and understand where to walk and what to do. A letter, I realize now, also gives us an exit.

•••

Your pregnancy: 23 weeks! With her sense of movement well developed by now, your baby can feel you dance. And now that she’s more than 11 inches long and weighs just over a pound (about the size of a large mango), you may be able to see her squirm underneath your clothes. Blood vessels in her lungs are developing to prepare for breathing, and the sounds that your baby’s increasingly keen ears pick up are preparing her for entry into the outside world. Loud noises that become familiar now—such as your dog barking or the roar of the vacuum cleaner—probably won’t faze her when she hears them outside the womb.

By the middle of my fifth month, my belly has the tight, round heft of a basketball. If I lie very still on my back, I see my skin vibrating like a drum. The pregnancy updates remind me this may be my baby hiccupping. I picture her turning and tumbling in her amniotic sea, flipping like a fish. As soon as nineteen weeks, the prenatal newsletters suggest, a fetus can start to perceive sounds outside the womb. Talking or singing to your baby is encouraged. Instead, I talk to my father. I tell him how I think I see my husband’s nose on our child in a more recent ultrasound, how she was leaning on her right arm and the ultrasound technician whacked my belly to get the baby to move so she could be sure that arm was there. I tell him I am scared. Not just of labor but of what happens after, of trying to be a good teacher and a writer and a mother and still hold onto myself, my adult, fully-formed-if-flawed self who drinks a little too much bourbon and stays up a little too late reading in bed and probably doesn’t eat enough vegetables, even at thirty-seven. I tell him there are things you hope for your child, and in my case, in addition to all fingers and toes, I hope she doesn’t inherit my anxiety and my deep desire to please and fix. I tell him how I hope she will be braver and better and more curious than me, and I wonder if every parent feels that way, if that’s why we keep on going.

I ask him what he hoped for me, when I was a piece of stardust, floating peacefully inside my mother.

I also ask my father questions. I start with the normal kind of questionnaire-like, the catching up conversation starters you might ask a college roommate you’ve fallen out of touch with. Do you still go to Maine each summer? Do you still run? Do you still love trees and know how to identify them by their leaves as well as their bark? Did you ever make that trip to the Grand Canyon? Am I even remembering that right, that you wanted to go there? If and when you went, were you as disturbed by the herds of gawkers with selfie sticks as I was? Because if so, here we can pause, laugh, hold onto something we have in common. We can take another sip of our beers before we move on to the more difficult questions, the ones he will never answer. In complete sentences, please consider how can a parent just give up talking to his children. For extra credit, what does my stepmother think of all of us? Does she urge you to contact us? Or, because it’s the easier thing to do, because that would open wounds and vulnerability, does she just not talk about it, as you surely do not talk about it, nor encourage my half siblings to talk about it. What are my half-brother and -sister like? Do you text them? Come on, really? You can’t not text with a teenager now. Do they wonder about us? Do you see us in them? What, to you, is family?

I tell him I want the lightweight freedom of forgiveness—for me and for him—but I’m mired in the thick, dark mud of anger. I tell him we can see each other’s broken places now, the cracks all of us as adults try to glue back together. The places where cracks have become invisible parts of us, the scaffolding that carries us through life with resilience and experience. The places where the workmanship was more hasty.

•••

Your pregnancy: 30 weeks! Your baby weighs almost 3 pounds (about the size of a large cabbage). You may be feeling a little tired these days…you might also feel clumsier than normal, which is perfectly understandable. Not only are you heavier, but the concentration of weight in your pregnant belly causes a shift in your center of gravity.

At a friend’s wedding in April, surrounded by a circle of new spring leaves, she and her new husband turn to each other and to his two teenage children from his first marriage and then all four of them pledge to love and support each other. It is the opposite of trite—it feels true and real, a very public way of making a new family. Later that month, I stop by my neighbors’ house, a lesbian couple who have each had a baby within a year and a half. I am there to go through hand-me-down baby clothes. In their living room, I fold tiny shirts the size of my hand, socks smaller than my thumb. The two mothers sit cross-legged on their polished wooden floor and ease their babies into their laps and at some point they both begin to breastfeed. So here is another kind of family. One block over, there’s a family with two white parents, one from France and one from Indiana, and two adopted black teenagers, and that is another kind. There is my middle sister, who has lived with her boyfriend for years. My single friends who bought houses for themselves and their dogs. Divorced couples with kids who still make a point of eating some meals together, or buy houses close enough for their kids to walk between, or don’t. All of these are families.

A few weeks later, my husband and I drive across the country. I am headed to write for a month at a residency in Washington State and we combine it with a route through the Southwest and then up the California coast. We stop in Los Angeles, and my aunt, my father’s sister in-law, insists we stay with them. They are good and generous to us; my uncle, my father’s younger brother, keeps saying, “We’re all family here,” and each time he does my heart opens and breaks all at once. Maybe the boughs on one side of my tree aren’t dead. Maybe they are leafing out. My husband likes my uncle, appreciates his collection of antique corkscrews and bottle openers, his home brewed beer, his stories and photos of camping and traveling with his kids throughout the West. I wonder what kind of father-in-law my uncle will be someday. What kind my father would have been.

•••

Your pregnancy: 37 weeks! Your due date is very close now…While you’re sleeping, you’re likely to have some intense dreams. Anxiety both about labor and about becoming a parent can fuel a lot of strange flights of unconscious fancy.

I sometimes forget what is happening to my body in these final weeks but then I will be doing something ordinary, like getting dressed, and I catch myself in the mirror, all round and curve, and I’m surprised what I’m now feeling in my heart and my womb is so physically evident to the rest of the world. My immediate future is written for all to see—motherhood, parenthood—inviting speculation and soothsaying from strangers. She’ll be a princess, she’ll be sweet. I just want my daughter to be. I trace my fingers down my linea negra, the dark, pigmented line that appears on many pregnant women’s stomachs, dividing their bellies into two tidy halves like the neat crease of a peach. My daughter inside, her head down low near my pelvis, positioned to eject. The scrape of her arms, the lean kick of her limbs. She’s becoming more fully formed each day. She is no longer a fish; she is a human with all her parts still safe inside, still unwounded, unbroken, unscarred. Still all possibility.

•••

Your pregnancy: 39 weeks! Your baby is full term this week and waiting to greet the world! He continues to build a layer of fat to help control his body temperature after birth, but it’s likely he already measures about 20 inches and weighs a bit over 7 pounds, about the size of a mini-watermelon.

On the late August day when my daughter is officially full term, a short letter from my father arrives sandwiched between a West Elm catalog and a Home Depot credit card offer. In romantic comedies and beach reads, this might have caused me to go into labor. Instead, I leave it unopened on the dining room table for a few hours while I pace around the house, making up things to do. When I finally tear open the envelope, I see his familiar tight, tall script, the handwriting of the Cheshire cats, the handwriting I’ve known since I could read. He says he has been meaning to respond, that he has been carrying around my letter. Happy for us. Small steps. Send details when you are ready.

Instead of a resolution, I’m left with more questions. Is it is too late to be a parent at any point? When is the damage done, or when can the relationship between a parent and a child be saved? Does forgiveness have an expiration date? When can I stop looking for hurt and harm?

Sometimes when we decide to have a child, we put a lot of faith in its power. We impose incantation on what is really just biology. Foolishly, we think it can save a marriage. Make us stronger. Make us kinder, more empathetic, more patient, into people we aren’t really, at least not all the time. We all know this in our hearts this isn’t true, and yet, as a species, we do this again and again. I knew having a kid would mean I would be a parent. But I also thought it would be the spell to have both my parents in my life. But even this, this growing person inside of my body, all these cells dividing and folding and weaving their way into someone new, a beautiful magic chronicled by ultrasounds and fetal heartbeat readings and genetic tests where we breath hope toward that deep, dark salty sea inside of me—even this isn’t enough to repair my relationship with my father.

The truth is I want to turn to my own parenting now, to my daughter and my chance. I want to push into the future rushing toward us like a wave. When people ask if we are ready, I am now saying yes, and yes, and yes. Yes, in that her crib holds a mattress and yes, her car seat is installed and inspected, and yes, we have built a fort of readiness out of diapers and pacifiers and tiny hand-me-down onesies, but also our hearts are ready, so ready, so open. Yes and yes and yes.

There is so much I don’t know about being a parent right now. I’m pausing here on this curb of pre-parenthood, waiting to cross a busy street to the other side, a street I will never cross again and corner I will never return to. But I carry this image in my head in these last hours and minutes. It’s of me and my daughter together working in the garden on an early spring day a few years from now. We dive our bare hands into the soil, turning over the dirt to wake it up. We knead in compost. We count earthworms. Then we feel bad and nudge them back into their dark homes. We rip into colorful paper packages, the seeds inside as small as periods at the end of sentences, all these tiny promises of radishes and lettuces and peas. We sprinkle them with a soft blanket of soil as if we were putting them to bed.

I will tell my daughter each seed is like a little wish for the future. I will tell her we plant them, and we hope, and then we just have to wait.

•••

LAURA GIOVANELLI is an essayist and writing teacher. Her other personal writing can be found in The Washington Post. She was a newspaper reporter for nine years and has an MFA from NC State University. She now teaches at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Follow

Follow