By Jacob Westlin

This past Sunday night, nine o’clock, did you know where your kids were? In Saint Joseph, Minnesota, one family thought they did. But, their eleven-year-old son on his way back from a nearby convenience store was abducted by a masked gunman. For four days, a massive search has been underway. This terrible crime has brought terror to the country’s heartland.

•••

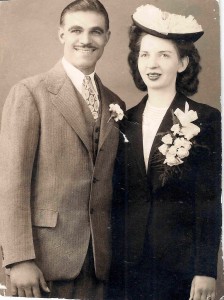

My dad and I sit together at the dining table. It’s a staple of the rarely used room—in place for years, rarely seeing guests. I study its light oak veneer, thinking it’s strange that while sofas and chairs and headboards and cabinets from thirty years ago almost always loudly proclaim their distinctive 1980s style, classic wood tables fit in any era. It doesn’t stand out, unlike the yellow and yellowing linoleum floor in the kitchen.

My father, sitting across the table from me, grips and re-grips the outside of his drink glass, spinning it maybe thirty degrees each time he does. I do this, too. Maybe it’s the condensation. Or maybe it’s some kind of nervous genetic twitch we both have.

It’s unusual, just the two of us drinking. Typically, however, our wives join us, but tonight they both reluctantly went to the same family baby shower. We were going to spend our Saturday night at the bar anyway, just us, but his arthritic foot is troubling him. Staying in doesn’t bother me. I rather enjoy an evening in the dining room—it reminds me of Christmas as a kid. I’m nostalgic like that.

The row of low-level cupboards beneath the buffet catches my eye and I chuckle.

“Do you remember when you bought us a Nintendo? What, 1986 or something? We played it right here on a little ten-inch TV.”

My dad smiles and turns around to face toward the kitchen, as though looking at the empty shelf where a video game console used to reside will jog his memory. I guess it did for me.

“I do remember! We didn’t really play, though. I took a five-second turn, and then you played for twenty minutes.”

“Yeah, I don’t get it. How could a little boy who never played video games be better than a thirty-three-year-old man who never played video games?” It wasn’t uncommon for me to tease my dad. Actually, it wasn’t uncommon for anyone in our family to tease my dad. It’s probably because he exhibits less vanity and egotism than anybody I’ve ever met. He not only doesn’t mind the casual ribbing but—particularly when it makes his sons or wife look better than him—embraces the barbs.

“Seriously. You kids pick up things way faster than I ever did,” he boasts.

“But check it out. Do you remember when I was lying down right there, playing Mario, with my feet on the glass cupboard?”

“And you kicked it out and shattered it?”

“Yes! And you never replaced it, look! Why didn’t you ever get new glass?” I ask.

“I don’t know. Maybe we cut our losses, figuring you kids’d just break it again. We had to be smart about that kind of stuff. Remember, bacon or bowling.”

His signature phrase.

“We could only afford one or the other when you were a kid. Your mom and I had to pick every week—bacon or bowling. We couldn’t have both.”

Fathers have a way of forgetting that they’ve told you the same thing monthly for a decade.

“I know, Pop.”

•••

Last week an eleven-year-old boy named Jacob was kidnapped from the streets of Saint Joseph, Minnesota. The effect on Jacob’s family has been obvious, but his kidnapping has also torn the tightly knit social fabric of the entire town.

•••

Just this year, my dad installed a flat-screen television above the fireplace. It doesn’t really fit; it’s mounted in front of cabinet doors, trapping inside more dusty, old dishware. My mother could’ve squashed the plan with a single sternly worded sentence, and she knows that. But now she gets the best of both worlds: when someone voices their objection to its poor placement, she can say, “I know, it looks ridiculous, right?” But she also gets to watch the Vikings while warming herself by the fire.

The TV is the only thing separating today’s dining room from the one in which I left cookies for Santa a generation ago. It certainly modernizes the cozy space, an apt symbol that distinguishes my folks’ current financial stability from the less certain future envisioned in the eighties.

The way Americans interpret wealth and socioeconomic position has always puzzled me. We display an inexplicably energetic pride when discussing how poor we used to be. People fight with one another, arguing passionately about who was the least well-off—as if the sheer act of having no money is commendable. And it seems to apply only to one’s past.

We love the idea that bad things in our past become good character-building foundations of our future. Maybe it’s true. Empathy and understanding are born from experience, I suppose. Isn’t it possible, though, that shitty situations are just that—shitty? Nobody would imagine telling a destitute family, unable to pay their bills and on the cusp of starvation, that they should really cherish these moments because they help establish essential personality traits.

I guess it’s easy to discuss the hardships of the past from a distant position. After all, we made it. Americans hold dear the rags-to-riches narrative, even if “riches” simply means you’re still breathing. We love to fit ourselves into some patriotic myth involving bootstraps and the like, despite rarely being applicable.

“What do you think of the TV?”

“It’s nice.”

•••

Posters of the abducted boy are reminders of an evil that is all too real. We have to protect our kids and we can’t take things for granted anymore. Now we have a new deadbolt on our door, and we lock it when we’re in the house as well as when we’re not.

•••

A muted baseball game is playing on the television. We aren’t really watching; it’s just flickering background to our boozy banter.

I freshen my beverage in the kitchen and sit back down at the table. In our conversational lull, between discussions of the bizarre election season and our fortune at not having to attend the family function, we both notice the ten-second local news ad at the end of the commercial break: an image of the other Jacob’s parents, sadly embracing, as the words “Jacob’s Remains Found: Confession Obtained” flashes beneath them.

The silence in the room morphs from an empty lack of words to a pregnant disquiet. Not an awkwardness, exactly, but an abruptly heavy moment weighed down with the unexpected drumming up of simultaneously personal and shared experiences.

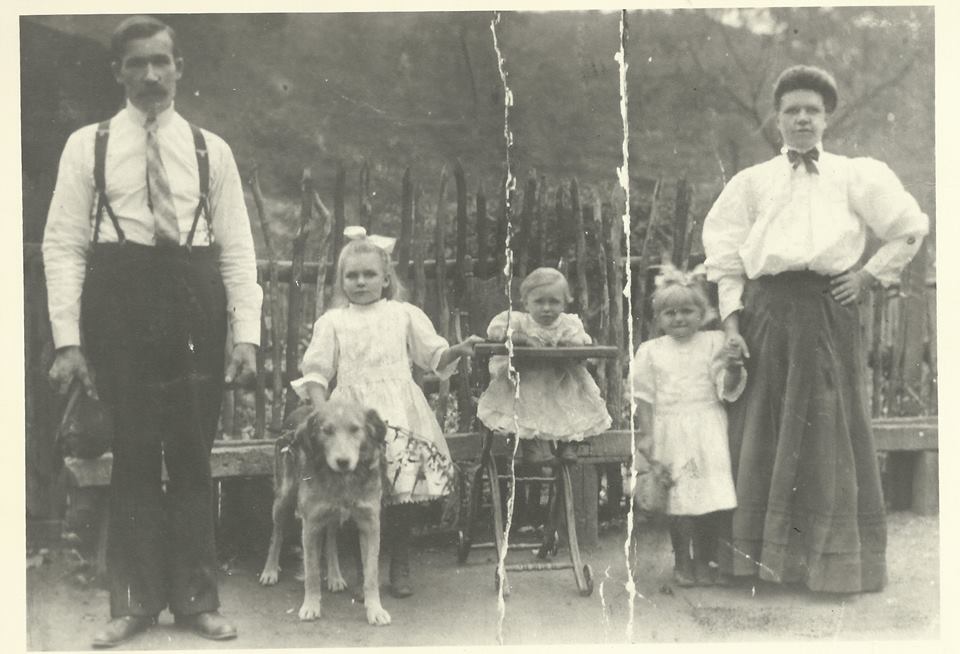

If you lived in Minnesota during the eighties and nineties, the case was naggingly omnipresent, a horrific event that framed the way families understood danger in their own neighborhoods. A small-town boy, an hour northwest of the Twin Cities, was biking back from the video store when, on a dark road, he was kidnapped—that panic-inspiring buzzword that engulfed the media and terrorized parents.

That was 1989. And, despite instant wood-scouring, sweeping national attention, and law-changing influence, the case was never solved. Until, it seems, today.

My dad and I are not particularly sentimental. The pragmatic emotional sterility of the men in our family irritates our wives, oftentimes with good reason. We don’t often passionately connect to news-story victims.

The stillness in the dining room now suggests a rare and unforeseen exception.

•••

They’re going through the nightmare of not knowing, and hoping that sometimes, in a rare incident, a child has gotten back that’s been gone for a long time. But all of the people sitting there today know the harsh reality: that lots of kids that are taken are not taken by some caring person and taken to Disneyland. They’re taken by someone who is into sexually assaulting children and, if you’re lucky, you’ll find the body in a field.

•••

Proximity to tragedy is a peculiar thing.

If you’re close enough to have a relationship with the victim, it’s all about them—as it should be. To know somebody personally affected by something as heinous as an unsolved kidnapping leaves no space for any emotion except withering sadness for the family.

On the other hand, if you read a news bulletin about a hurricane or flood or earthquake or uprising half a planet away, you’re granted—if not altogether legitimately—a certain disconnection and the ability to simply mutter, “That’s too bad,” before eating dinner.

There is also, however, a third middle ground, a grayish terrain where genuine grief or emotional detachment gives way to narcissistic self-preservation.

The immediate response in Minnesota after the kidnapping case was truly touching. I remember natural anguish and heartache, leading to volunteer search parties, songs, and the genuine coming together of community residents. There was real statewide concern for this boy and his family.

What happened simultaneously, though, was an almost palpable wince, a stiff shrug that transformed empathy for others into locked doors for yourself.

Displaying compassionate warmth for the parents and taking safeguarding precautions against potential dangers are not mutually exclusive. But sometimes, with just the right adjacency, the flesh-and-blood victims become caricatures and the nebulous threats blossom irrationally.

“How could this happen here?” was the frightful inquiry of the day. The incident materialized an already sensational perception of safety, or lack thereof. Dramatic movies of the week, a bygone favorite of network primetime television, assured us that unscrupulous predators lingered around every corner, waiting for the right guard-down moment to strike a randomly targeted stranger. And, before the Saint Joseph abduction, it was easier to dismiss these crimes as confined to New York or California—not wholesome flyover country. Maybe the world was a scary place. Maybe ABC was right.

“I remember that so vividly.” My father breaks the silence with an altogether appropriate cliché. In my trance I had momentarily forgotten I wasn’t alone.

“You’re telling me.”

“You remember it? You were only five or six years old.”

He queues up an interesting point. Because my nostalgia lobe is monstrously oversized, and because I spend so much time contemplating the changing cultural conditions of my boyhood versus those of my as-of-yet unborn children, I often view things from a skewed and manufactured perspective. I wasn’t a parent in 1989. But, as a child during the regional hysteria, I did, in this situation, have a very intimate and unique relationship to this case.

•••

We’re not really going to let Jacob walk to school by himself, are we? I know he’s done it for months, but with everything that’s happened, I don’t think we should. I’ll walk him there. At least for the next few weeks. To make sure nothing happens.

•••

Until first grade, I had a forgettable name. Jacob Westlin was just the name of another average-looking white kid. Then, in October of 1989, as the other Jacob was victimized in the most infamous crime in Minnesota history, it became something else entirely. It became close enough.

Overnight, classmates began pointing at me and yelling clever quips. “Found him! Found him!”

The entire state was in a frenzy over this missing child and I, sixty miles away and with no more connection to Jacob than sharing the first seven letters of his name, became his tease-able avatar—the ceaseless butt of adolescent jokes.

At first it was kind of surprising and funny. But, as the case continued to receive pervasive coverage and word spread about my coincidental name, the casual taunting rapidly devolved into relentless mockery and rejection. One boy was particularly brutal, the unofficial leader of the witch hunt, soliciting support from willing classmates: Ian. But he didn’t pronounce it ee-an. No. It was eye-an. I’ll never forget.

He made sure, at least during a few harrowing months at the end of 1989, that nobody would come near me on the playground. “Stay away from that kid, everyone, or you’ll get kidnapped!” And everybody would play along, in this case by not playing with me. Kids in groups are not unlike adults in groups, turns out. Easily led astray by one mouthy facilitator.

I remember being very upset, trying to apply kiddy logic to a completely illogical and visceral problem. “I’m not that Jacob, guys! You know that, right? Come on!” This proved useless.

“Do you know what hell I went through in first grade?” I half rhetorically ask my dad.

“No, what do you mean? Because you were afraid of being abducted?”

It’s such a fatherly response, anxious to protect his son from the overtly conspicuous dangers of the world when the real soul-altering crises are almost always more intimate and invisible. But it’s not his fault. I never told him about the tormenting.

“No. Everyone made fun of me because my name sounded so much like his.”

My dad half scoffs and leans back in his chair. “Well, that’s dumb.” Indeed, as I cite the ridicule aloud, maybe for the first time in decades, I realize how absurdly innocuous it sounds.

“Uh, yeah, of course. I knew there were more important things going on with that kidnapping than my silly sadness,” I lie, stumbling over my words in embarrassment. I lie because I’m ashamed of feeling sorry for myself. I lie because the other Jacob was sexually assaulted and murdered, and I was subtly picked on. I lie because people have a way of ascribing wildly inaccurate nobility to previous behavior, built upon years of hindsight and experience. And newly discovered shame. The truth is that, in my childish mind, I was the victim. I didn’t know this other Jacob and I was angry at him for being taken.

Young minds have a remarkable proclivity for tunnel vision. It would be reasonable to expect children in this hysterical climate to become terrified of the lurking hazards all around them. The reality is that while kids are the targets, and adults go to painstaking lengths to construct in their sons and daughters a skeptical guard against strangers, most of them leave worry to the parents.

I was never afraid of being taken. I was afraid of having no friends.

Authentically remembering events from years ago is a trickier pursuit than re-experiencing the emotions they spawned. I remember very few actual teases and hardly any of the kids that painfully avoided me. But I do recall the paralyzing aloneness, feeling like my tiny world was caving in through no fault of my own.

I do, however, distinctly recollect lying in bed, thinking I had a choice. I could keep fighting or just embrace the joke—show these kids that it didn’t bother me and that I was a fun, normal boy.

•••

Hey, guys! Let’s play hide and seek—try to find me! You know the police couldn’t!

•••

Jacob didn’t get a choice. The other Jacob. I think about this for a while.

My dad adjusts in his chair, likely reading my discomfort and probably feeling bad for disregarding my infantile problems. He would never intentionally dismiss something important to me, and he now perceives his cavalier response as inappropriate.

“I’m sorry. I’m sure it wasn’t easy.”

He didn’t need to apologize. He’s my father, and I’ll always give him the benefit of the doubt. Also, he wasn’t wrong.

“No, it’s fine. It’s just funny, isn’t it, the things you remember? It’s like, I should be feeling so terrible for the family, and I do, really, but seeing them just makes me think about—you know, my own shit. I don’t know, sorry.”

My dad nods, making eye contact this time, almost overly engaged. He doesn’t say anything for a while after that, eventually averting his eyes down to the table with one hand again spinning his drink glass. He’s deep in contemplation and I study his face. People have this view of their parents as stoically static.

My father uses quantifiable milestones to mark my maturation: graduation, college, moving out, starting a career, finding a wife. None of these markers exist for me to assess my dad. He evolved from a probably frightened twenty-nine-year-old father to the veteran rock he’s becoming without me even noticing. He’s always just been Dad, and the lack of lifetime-accomplishment receipts now, for the first time, bothers me. It’s like an absent parent’s lamentation at missing their kid grow up—I feel an odd regret, like I’ve failed to appreciate my own dad’s evolution while being so enthralled with my own.

He was not, and will never be, a complete and infallible adult. None of us will. I am struck now with the simultaneous profundity and triviality of this realization.

“Twenty-seven years later, they close the case,” he finally says. “A lot’s changed.”

“What do you remember about the whole thing?”

He perks up.

“Oh, man. It was mortifying, as a parent. But we still had to raise you right, you know?”

I didn’t.

“What do you mean? Did it change the way you and Mom parented?”

“Oh, we had our own uncertainties, for sure.”

•••

He’s going to be fine.

But what if he isn’t?

He will be! I’ve had enough of this! How is he ever going to learn independence, or believe that the world is anything but a nightmarish place full of maniacs looking to kill him, if we bring him to school, hand in hand, until he’s seventeen?

But—

But nothing. Let him go.

•••

“I give your mother a lot of credit,” my dad blusters, as he often did—not incorrectly. She’s a tough lady, a good mother who was always willing to make hard decisions if it meant raising responsible men.

“The right balance between independence and smothering. We had a hard time with it. You know me—I worry about all the stupid details. Your mom, rightly so, made sure you had your space—saw the big picture. I feel like that was a big deal, even though you probably don’t remember it.”

I didn’t. But I listen intently, enraptured by this completely new information. I realize, at this moment, for the first time, that the monumental event that so influenced us individually had never been spoken about collectively. I don’t think it’s because we were purposely withholding information. Maybe it just didn’t seem relevant until now, even if the relevancy of who we’re becoming as human beings is all around us.

•••

JACOB WESTLIN is a writer, copyeditor, and humanities professor from Minneapolis. He has numerous publications—including a book titled Poker Players are Narcissistic Sociopaths, a collection of tongue-in-cheek poker observations—though this is among his first forays into creative nonfiction.

Follow

Follow