By Melissent Zumwalt

Earlier this week, my husband and I arrived at my childhood home to help my mother move. She has lived on this spot for thirty-four years (since I was two years old). The last twenty-five of those years here, she spent against her will, a captive, hating this place, begging my dad to move. He passed away 363 days ago.

Since our coming, I often find Mom staring vacantly into the air, slumped over on the couch, listless. After decades of seeking an escape from this house, on the eve of her ultimate freedom, she is morose, maudlin, exhibiting something akin to Stockholm syndrome.

It now feels like maybe this whole move was my idea, that I thrust this upon her too soon after Dad’s passing. But the fact of the matter is, however we ended up here—it’s happening. The new owners take possession in five days, and somehow we have to get Mom out of here, physically and emotionally.

•••

The house itself is nothing special. A 1978 ranch model situated on an acre of land in the rural Willamette Valley of Oregon. It’s located in an unincorporated area not claimed by any town: farm country.

My parents were not farmers, but most of the families in this area are, or were back then. The soil of the Willamette Valley is the most fertile in the nation, its own form of “black gold.” This rich earth alleviates the need for a green thumb to succeed as a gardener. There was the time Mom dug a hole in a corner of the front yard and simply threw our Halloween Jack-o-Lantern into it for disposal. We forgot about it until the next fall when a robust pumpkin plant emerged from the spot, gracing us with a bounty of fresh pumpkins.

Acreage of berries, hops and hay proliferated in the region, the air often permeated by the stench of manure, a rich scent of cow excrement I found revolting as a child. (How dramatic we were as kids on the school bus, making choking sounds and pantomiming gagging as we rode by particularly ripe fields). Later, it became a smell as nostalgic to me as wood smoke or pine.

The stillness of the region is all-encompassing, to the point of suffocation. A childhood friend slept over one night and found the force of the silence so unnerving she could not rest. The distance between houses and scant traffic leads to a night sky that is total in its blackness. Until I left home, I didn’t appreciate how few people had the opportunity to see the evening stars.

“Going into town” from here required a commitment. It would sound like we were loading up a wagon train, “Hey, we’re going into town. Do you need anything?” Trips like this were premeditated and would not be repeated for another week. With the time it took to travel out and back, there was never any concept of “running to the store” for a forgotten item or an impulse purchase. The same was true for getting to school or going to friends’ houses. Everything had to be planned, coordinated.

I was never interested in any of it, the rural lifestyle—and truth be told, my parents really weren’t either.

The house was chosen based on its physical isolation. There was no neighborhood of which to speak, no community, no one to cast judgment on us with disapproving eyes. My mom would tell me, only half-jokingly, that we ended up out here because we were “run out of town.”

When I was a baby, we lived in “city” limits (a bursting metropolis of less than 5,000 people). In those early years of our family, perhaps Dad’s hoarding affliction could still have been misconstrued as severe messiness. The garage filled up and spilled over with things—broken bicycles, greasy spools of rope, dilapidated cars, empty paint cans, rusty ladders—occupying the yard, the driveway, like a garbage dump.

Mom often recounted a story of one afternoon when she and I were home alone together. Holding me on her hip, she answered a knock at the door, and to her surprise, found a policeman standing there. He told her there were town ordinances. She was going to need to clean up her yard or he would have to fine her. With the pride she took in her appearance and her impeccable housekeeping skills, she choked up with embarrassment. She did not mention the mess was my dad’s. She spent the afternoon with a neighbor woman feverishly cleaning up the small yard and garage. When my dad came home, he was enraged. He hollered at her, red-faced, for touching his things, accusing her of trying to get rid of him. My dad was over six feet tall and barrel-chested. When angered, he was a charging bull. Mom looked for a way to make it work. Within a week, she found the house for sale in the country and they moved every last item away from the disparaging gaze of city life.

As an adult, I later recognized the extreme isolation I felt as a child, an isolation carried with me throughout my life, was a deliberate construct.

I didn’t anticipate moving Mom out this week would hold much emotion for me. After leaving home at seventeen, my return visits were infrequent at best. I preferred my parents, or more specifically, my mother, come to see me wherever I happened to be living—often in the most vibrant, densest places I could find. In my urban apartments, the sounds of ambulance sirens and the constant whirring of traffic soothed me to sleep like a lullaby. I gravitated to places pulsating with indicators of life: streetlights, headlights, neon lights. The non-stop presence of humanity was inescapable even inside my apartments, where the smell of my neighbors’ cooking infused the air and it was possible to hear them singing, coughing, laughing through the thin, shared walls. I never had to be alone.

•••

The house on Killins Loop served as the physical manifestation of our family’s neuroses.

Mom had her spaces, the front of the house and inside, where her OCD reigned. What, to most people, would be termed “spring cleaning”, constituted her normal weekly routine—fully emptying cupboards and scrubbing down shelves, vacuuming under couch cushions and flipping them over to preserve the longevity of the couch, washing walls, scouring the oven, moving the refrigerator to mop behind it. The pervasive aroma of Pine-Sol signaled her movement from one room to the next. Her cleaning was not cheerful. It was beleaguered, martyred. She’d clean through the house like an army on the move, muttering along the way, “None of you would care if I dropped dead except you wouldn’t have anyone to clean up after you.”

She enforced strict rules with us (never sit on the bed, never eat outside the kitchen); issued protocols around putting things away (precisely how to fold the blanket on the couch when done using it, specifically how to tuck the chairs back in under the table); told us exactly where things should go (shoes off upon entering the front door, how and where to line them up), taught how to turn appliances on and off to keep them functionable for maximum lifespan. I grew up under an uncompromising regimen, like being raised at basic training by a drill sergeant.

And Mom conceded Dad his spaces, mostly outside, the back acre and the barn, where his hoarding dominated. His stuff piled up to the rafters of the barn and cascaded out, covering the yard and becoming entangled with the rampant, wild vegetation, incorporating crazy things like boat motors (we had no boat) and discarded school lockers and unwieldy strips of sheet metal twenty feet long and objects that had become unrecognizable over time. There was no system to any of it. Wherever he put something down last, that’s where it stayed, and he heaped new things on top of old as he brought them in.

Dad’s compulsion tried to overpower hers. His junk would begin to infiltrate the inside of the house through the tacked-on sun porch he’d built, accumulating around his desk, on the table, starting out innocuously as stacks of receipts, losing lotto tickets, used nails. But then it expanded into mounds of inoperable fans, dismantled clocks, warped VHS tapes, a flat tire. Mom fought it back like a wildfire, holding the line, watching for drift—for things finding their way to the kitchen counter or the bedroom. She would get firm with him, demand it all migrate back to the barn, and start moving things out herself. Which led to the inevitable eruption of gruesome shouting matches. The cycle repeated itself, year upon year.

•••

As I pass through the hall towards the bedrooms, a loaded moving box weighing down my forearms, the hole in the closet door catches my eye.

I recall with exacting clarity the night it happened.

My older brother, Chris, fifteen at the time, returned home from being out with friends. He disappeared frequently back then, sneaking out through his bedroom window, going missing for days, showing up unexpectedly at odd hours, already drinking heavily and abusing hard drugs. That evening he slunk in through the front door, trying to make his way unnoticed, past where Mom and I sat in the family room watching T.V. But Mom confronted him in the hall, both of them primed for an altercation.

“Look at me,” she demanded, cupping his chin with her palm to turn his face her direction. “You’re high again.”

“No, I’m not,” he retorted, anger seeping from him already.

“Chris, I can tell by looking at your eyes. I know. Don’t lie to me!”

“I told you! I’m not high!” he yelled.

“And I told you not to come home like this!”

And then he burst and started punching the closet door with his bare fist, repeatedly, screaming with each hit, “Fuck! Fuck! Fuck!”

My beautiful brother turned into a demonic thing right before my eight-year-old eyes.

No one ever fixed the hole. There isn’t time or reason to now. The buyers take ownership in four days, it will be their problem then.

•••

Mom wanders aimlessly through the house, back hunched, arms dangling at her sides. She loosely grasps a half-formed cardboard box by its flap in her right hand. The box slaps her leg with each shuffle step, dragging along on the floor beside her.

“I don’t know what to do with this,” she mumbles, gesturing to the box. “Do you need it somewhere?”

One step leads down into the house’s sunken, formal living room, situated directly off the front entrance. We approach the built-in bookshelves along the back wall. Mom sits on the brick stoop in front of the fireplace, adjacent to the bookcases. I sit on the floor in front of them and take books off the shelves, one at a time, holding each up for her assessment. Her collection is chockfull of mysteries and biographies, her favorites.

Pulling out the next book, “Black Dahlia?”

“Donate,” she says.

In my youth, the popular novels she’d kept from the 1960s and early 70s intrigued me the most, providing me with a window into a bygone era. Peyton Place. Valley of the Dolls. Fear of Flying. Coffee, Tea or Me. I used to sneak her books off the shelf while she was away at work, read and replace them before she found any missing. Part of the taboo was the content of these books, considered racy during their time. But more important was the fact I didn’t want her to know I had gone into the living room to get them.

We were not supposed to enter the living room.

The living room was an anomaly, the nicest spot in the house. Mom and Dad replaced the room’s green shag with a plush, white carpeting. She’d feared we would sully this pristine new floor with our soiled feet—and she came from an old-fashioned upbringing that believed a formal living room was for entertaining only.

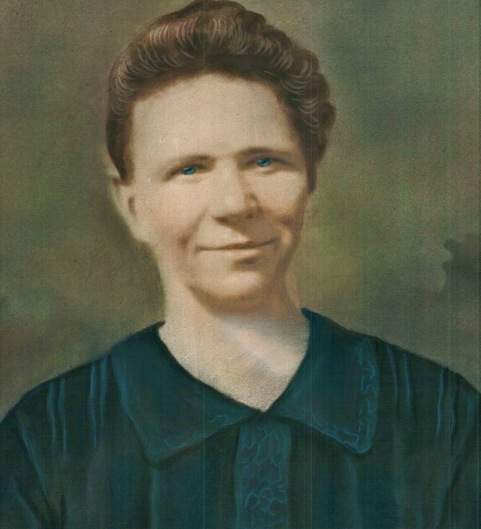

More than just the thick, luxurious carpet and all Mom’s books, the living room was where she kept a globe, a painting of her mother and a formal portrait of Mom, Chris, and me as a baby. There was a full-length couch with matching love seat and a proper coffee table. As a kid, the room seemed so spacious, so beautiful. I wished we were allowed to use it more often.

The problem with saving our best areas for entertaining was that we never had guests. Mom’s side of the family all remained in West Virginia, and although Dad’s family lived locally, none of them spoke with each other, ever. Mom and Dad had no friends, or none outside of work, or at least none who would travel the great expanse to visit us at our home.

•••

The inaugural owners occupied the house for two years, then Mom and Dad bought it in 1980. When my parents acquired the house, it cost $80K. They had $30K to put down from the sale of their place in town. With Dad’s military service, they were able to secure a loan through the VA for the remainder of the purchase price. Today, thirty-four years later, Mom owes $150K on the house. The calculation is incomprehensible.

Decades back, Dad went into business, opening a security firm with an irreputable colleague. Over the years, the firm struggled and Dad’s partner convinced him to put our house up as collateral for another loan. Dad took Mom to the bank to sign the papers without telling her the purpose of the visit, capturing her signature through the element of surprise.

As his partner steadily embezzled money and failed to pay taxes, Dad never questioned the accounting, never saw the books, until the whole operation was on the verge of collapse. Dad’s signature held him accountable and we were assured to lose the house. I was eleven and they didn’t discuss things like this with me directly. But I overheard their arguments.

Mom, yelling, “I can’t believe you did this to us! We are going to lose the house!”

Dad, also yelling, “We’re not going to lose the goddamn house!”

That was the language they used. “Lose the house.” Lost—like a set of car keys, or losing a sock. Abrupt. One day the keys are in hand, and the next, lost. As a kid, I tried to imagine what it would look like, when we “lost” the house. Would it be like the time our mini-van got repossessed? When Dad drove it to work and came out to find it missing? One moment it was ours, and the next, gone forever.

Would it happen quick, like a fire, enabling us to take only what we could grab in that moment? A favorite dress and whatever book I happened to be reading? Or would we know they were coming, like a scheduled appointment?

I worried that when the time came, I wouldn’t be allowed to stay with my parents any more. That they would be seen as officially unfit. I tried to prepare myself.

One Saturday afternoon, Mom and I wandered through the mall. Even as a kid, I understood shopping was Mom’s addiction, her way to deal with Dad and Chris and life. The mall allowed us a neutral setting where we could experience happiness, at least for a moment. It felt safer for me to broach sensitive topics there.

Mom stopped to peruse a blouse, folded neatly on a display table. I watched her face for the moment of transition, the split second between when her attention was freed from the merchandise but before we marched onward to the next item. When the instant arrived, using clear inflection, low volume, I broke out my rehearsed inquiry, “Mom, if they take our house away, will they take me away from you and Dad?”

“What?” her voice terse, my words breaking her shopping-induced reverie. She did not make eye contact, but her annoyance with me was evident for thinking this, for saying these words out loud, in public, where other people might hear them. “Of course not,” she hissed. “Look at all those kids who end up living with their parents in cars.”

I tried to envision it. The four of us cramming into some used car for the night, like something out of an afterschool special. For what it was worth, I found consolation in her response. My bedroom might be taken from me, but my family would not be.

Armed with this new information, I waited for the day we would “lose the house.”

•••

With forty-eight hours remaining until moving day, I walk into the kitchen for a cup of coffee and some yogurt. Mom stands at the kitchen sink, dishrag in hand, crying. I approach her from the side, invoking my most soothing tone, “Are you feeling sad about the move?” It seems an obvious question, but she’s been pining to leave for decades.

“Yes, this is my house. I have a house, and I’m moving to that … that stupid condo. I’ve lived here for thirty-four years,” she replies.

“I know, it’s a big change,” I say,” What’ve been some of your best memories here?” More than just changing the conversation to something positive, I am legitimately curious what she is going to miss.

“Well, there’s a lot of good memories,” she sniffs, “Like, when we took you and Chris to Disneyland.”

For me, the irony is immediate. Her fondest memories of the house are when we were away from it.

“Yeah, that was a fun trip,” I concede. “And we did make it to Disneyland two times.”

“We did?”

I guess she blocked out the second excursion. I don’t blame her. The first time, when I was seven and Chris fourteen, we drove in Dad’s old pick-up truck all the way down I-5 from Oregon to Southern California. Mom and Dad up front in the cab, Chris and I riding in the truck bed, under the canopy, sitting on foam mats. We visited the Magic Kingdom, enjoying the Pirates of the Caribbean and It’s a Small World, eating cheeseburgers in restaurants, our one true family vacation.

But the night before the second trip, just two years later, Chris ran away from home again after a verbal brawl with Dad. My parents debated whether to cancel the trip. Since they had taken leave from work and made all the arrangements—a rarity for them—they decided the three of us would depart as scheduled.

Upon our return, we found the family room window shattered, the house in disarray. Apparently, Chris did not have his house key. He and his friends broke in while we were away, searching for things they could sell for drug money. His friends stole several of Dad’s guns and Chris pilfered whatever cash Mom tried to keep hidden for emergencies, ransacking her personal drawers. When I try to summon memories from that second outing to Disneyland, all I see is broken glass littering the family room carpet.

Standing there with Mom in the kitchen, reminiscing about the few positive moments she conjured up, I mentally search for heart-warming reflections of my own contained within these four walls.

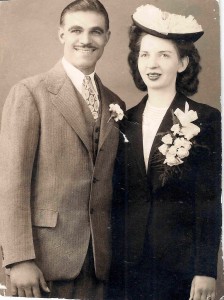

My real joy in the house came from the studio. In Mom’s younger years, she pursued dance as a professional career. Once she had us kids, she wanted to continue her dance career as a teacher. Mom had a conversation with Dad and asked him if his job was secure, if it could support the family while she launched her dance studio. He replied yes, in full confidence. Then he reconstructed the garage at Killins Loop into Becky’s Dance and Exercise Studio. He bricked over the garage door into a solid façade, sprung the floor and lined the walls with barres and mirrors.

Mom opened for students and six months later Dad was fired from his job for stealing. He could not stop himself from bringing things home, amassing more, piling up his hoard, regardless of where or how he obtained these things.

Needing a reliable paycheck, Mom eventually shuttered her business, but the physical studio remained, an homage to her unfulfilled dreams. Over the years it inevitably became a glorified storage room, but I always kept enough of the floor cleared to dance.

I hated Dad’s mess and his instability. I hated Mom’s regimented rules. I hated my brother’s intoxicated anger. I hated being so alone all the time. Too far to walk or bike to anything as a kid. I took it all out in that studio. In the endless monotony of summer, with nowhere to go and no way to get there, sometimes I exercised up to four hours at a time. Finding my solace through movement and music and endorphins. Waiting for the day when I could finally leave it all behind.

•••

Night falls on our last evening with the house, my childhood home.

I stand alone in the doorway of the darkened laundry room and look at the emptied dining room through to the kitchen and the family room. Thinking back on all our memories, wondering if, after thirty-four years, our family’s unhappiness has taken on a life of its own that will haunt this space once we leave.

Earlier today Mom and I took a break from chores and went for a short walk down our country road. As we meandered, the omnipresent, low-slung cloud cover parted, revealing Mt. Hood’s noble peak. Realizing I never found out how we managed to keep the house, I used this opportunity to ask.

“Oh, we were going to lose it,” she tells me with certainty. “We had to make a minimum payment of ten thousand dollars right away or it was gone. There was no way we had that. I was preparing for us to leave. But then, at the last minute, Aunt Ruth sent me a check for it.”

The knowledge settles with me. “So, she’s the reason we could stay.”

“And then, we were just broke,” Mom continues. “After paying the IRS on the back taxes each month, the double house payments, we had nothing left, and I was working two and three jobs. Trying to catch up.”

This part of our story, I remember well.

Staring now into the darkness of the house, my viewpoint shifts. I understand, viscerally, with the perspective of adulthood, how hard my mom fought to keep this place, for us.

What she did was remarkable.

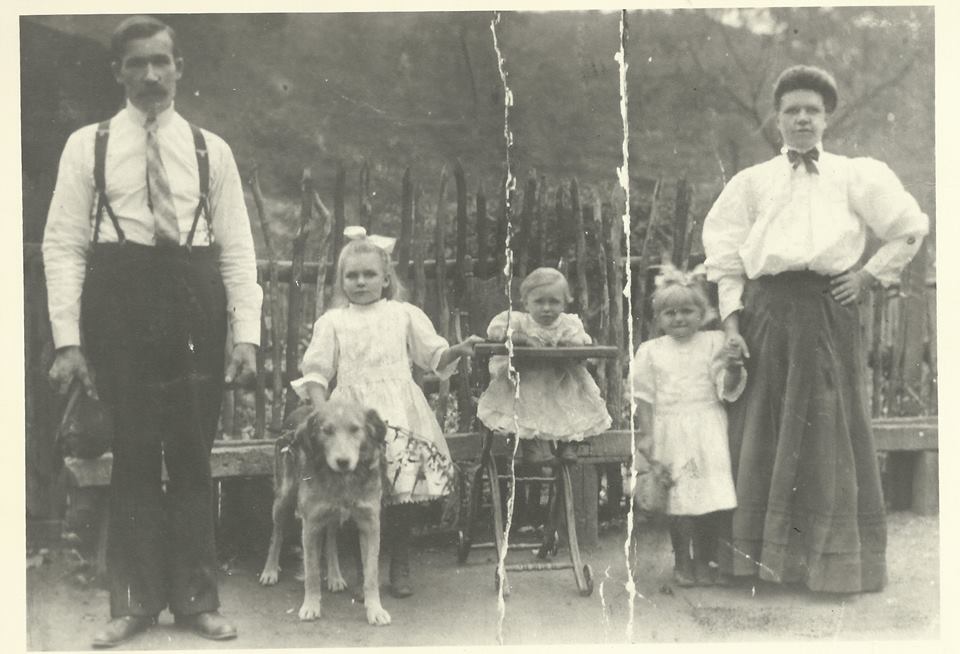

Mom and her sister did not finish high school. Their lives were plagued by turbulence and upheaval, never having enough stability to establish a rhythm to their schooling or to develop close friendships with other children.

Mom recalls instances in her youth of waking up in basement apartments, the floor flooded to her ankles, or life in sweltering attic units where her father could not stand erect. Because of her own father’s addictions and abuse, she wanted things for me that had never been afforded to her. Compared to the poverty she grew up in, our home on Killins Loop was palatial, and I, its beneficiary.

This house provided me with the foundation to finish high school, to be the first in the family to graduate college. As much as I had hated it, this house provided me with a stable platform to spring forth into the world and find my way.

•••

The realtor told us we could just leave our house keys on the kitchen counter and be out by the afternoon. But I burned with curiosity—who were these people that would occupy the space that had occupied me for so long? We arranged to hand over the keys to the new owners in person.

There is no logical place for us to wait for them. It is not really our house any more. This moment exists in a vortex, no longer part of our old life, the life that contained Killins Loop, and the new lives not yet created.

On this early September afternoon, simply remaining outside is most comfortable. The three of us—my mom, my husband and me—take a seat on the front concrete step.

The house never looked as good as it does today. The sun shines warm and inviting, not as overly intense as in the summer months. The sweet odor of freshly mowed lawn floats on the breeze and the branches of the apple tree hang heavy with Gravensteins. Mom swept the front porch, the sidewalk, and her window washings make the front of the house sparkle.

“What time is it?” Mom asks.

“5:05,” I reply.

“They’re late,” she says.

Another five minutes creep by before we notice a turquoise mini-van approach. This must be them. No other cars have driven by since we’ve been outside. The three of us stand with expectancy.

As the van pulls into the gravel driveway, I try to catch a glimpse, a precursor, of who is inside. After endless seconds, a clean-cut man in khaki pants and a woman wearing a sun dress, both in their early thirties, emerge. I spot a small face press up against the back window. The woman slides open the passenger side door and a jumble of little limbs and torsos, attached to four hearty children, tumble out.

We walk towards each other. Mom appears small, timid. She extends her hand to them, “I’m Becky,” she says.

The woman smiles with compassion and takes Mom’s hand in both of hers. “I’m Susan,” she says. “Is this your house?” She seems genuinely interested to meet Mom, as if she is grateful to her for this new home.

“Yes,” Mom replies, tears forming in the corners of her eyes.

Susan turns to the man beside her. “This is my husband, Dan, and we just love your house. We are so thankful. This will be our first house. Oh, and these—” she gestures to the four kids who appear to range in age from three to eleven, who brim with uncontainable enthusiasm, and who have already begun chasing each other around the front yard—“are Elizabeth, Stephanie, Jennifer and Jacob. He’s our youngest.”

We smile in acknowledgment and finish our introductions. We learn Susan and Dan are both schoolteachers. Their delight over having room for their children to play is demonstrable. They already talk about planting a garden.

“Can we walk through the house together?” Susan asks. Although the invitation is directed mostly to my mom, her offer provides me a needed moment of closure.

As the five of us enter the house, the kids run to catch up. They barrel through the front door and from the cramped interior hallway, drop down into the sunken living room. All four of them skipping in circles, unfettered, through the empty room, nimble feet on white carpet. I wonder how this family will use the living room. The children are so natural in the space, so joyful. As the eldest girl clasps the young boy’s hand, I pray for them. That they will gather in here, play games together, eat popcorn on couches, laugh with each other here, love each other here.

•••

MELISSENT ZUMWALT is an artist, advocate and administrator who lives in Portland, Oregon. Her written work has appeared or is forthcoming in the Whisk(e)y Tit Journal, Full Grown People, Oregon Humanities’ Beyond the Margins, Sisyphus, Pithead Chapel and elsewhere. She learned the art of storytelling from her mother, a woman who has an uncanny ability to recount the most ridiculous and tragic moments of life with beauty and humor. Read more at melissentzumwalt.com.

Follow

Follow