By Sara Bir

In three hours, I have a chemistry exam I might fail. I say “might” because I could cram desperately in the three hours between this moment and the time of my probable failing, and I’d rather spend those three hours doing something useful. Cramming is a deceptive word for panicking.

This feeling of looming academic doom is familiar, and I’m skilled at managing it calmly. Somehow I passed chemistry when I took it in high school, over twenty years ago. (“Somehow” was actually Betsy, my saintly lab partner, who happened to be the daughter of a chemistry teacher.) I recall very little about our curriculum—octets and ions and moles—but I remember sitting close to the window, because through it I observed the antics of a brazen woodchuck that lived in the woods bordering the school grounds. I also remember looking at the graffiti on my desk, which read, “Paige and Erin are DIKES.” They were not, as I knew firsthand, because Paige and Erin were two of my best friends. I also knew how to spell dykes properly, with a Y instead of an I, but it took me a few weeks of staring at the doubly incorrect slur on the desk before I realized I could simply erase it. If high school chemistry had tested me on groundhogs and stupid rumors and the ability to sketch various martyred saints in my notebook while listening to the Doors, I would have received an A.

And now, this exam nears. All these years later, I thought I had learned my lesson about chemistry class. Unlike the first time, I have applied myself as much as possible, because the topic is genuinely interesting to me—or at least the parts that have to do with cooking, because I am a chef. I’m teaching a charcuterie class next week, and deadlines loom: finish typing up the recipe packet, order duck legs and duck fat, drive all over town to purchase ingredients. Chemistry and charcuterie both require my full attention. My heart is with the pig.

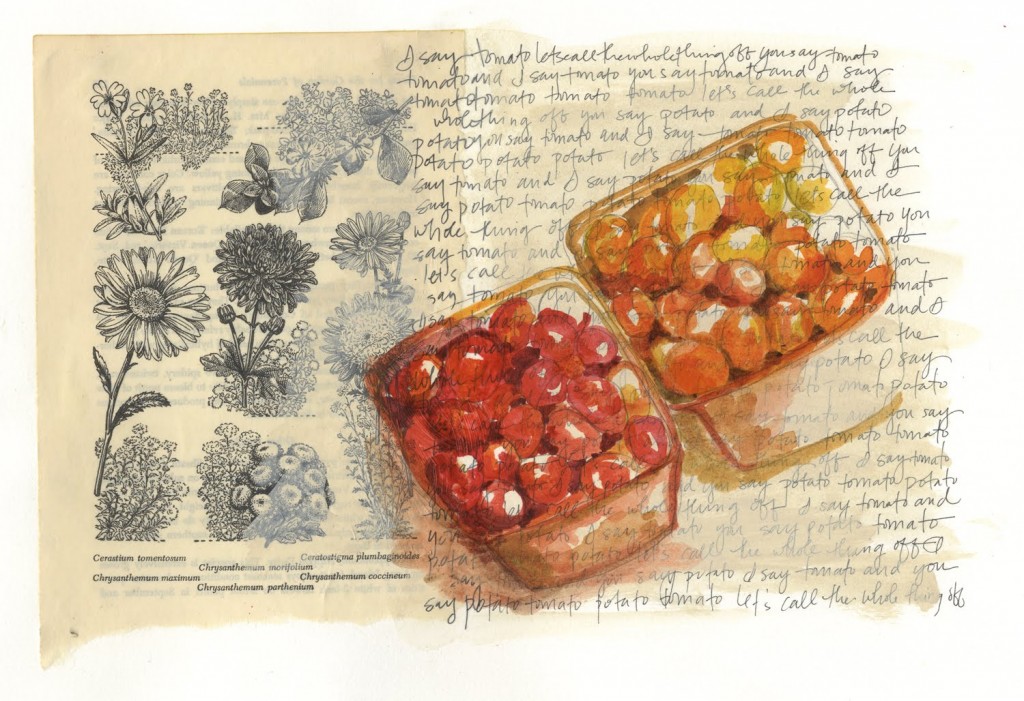

Charcuterie is the art of preserving meat, most often through curing, smoking, or drying. Different chemical reactions make it all possible, sodium and nitrogen compounds mingling and swapping electrons in atomic versions of French kisses and extravagant, multi-player sexual positions. NaCl. NaNO2. KNO3.

Of course, I can’t write balanced chemical equations for what happens when you rub kosher salt, brown sugar, and sodium nitrite on a slab of fresh pork belly and let it sit for a week or so (some juniper berries, peppercorns, sage, and bay leaves are helpful, too). I just know that it happens. You put the dry cure on, flip the belly over every day to make sure it cures evenly, and, five to eight days later, it’s bacon. (You can omit the sodium nitrite, and the myoglobins in the meat won’t turn that hammy pink color, but the end result will still be delicious.) Then you rinse off the dry cure, at which point you can smoke it or cook it off in the oven. It’s not rocket science, but it is chemistry. What you wind up with is different from what you started out with.

•••

Always chemistry awaits. Chemistry awaits because I don’t have a Bachelor’s Degree. I never wanted one, ever. I didn’t even understand the difference between an Associate’s Degree and a Bachelor’s Degree when I went off to college, because I thought college was for browsing for used cassette tapes at record stores and drinking gallons of coffee at noisy cafes while reading a stack of the local alternative weekly newspapers. I dropped out of college before I failed, which is like quitting a job right before they can fire you. This didn’t comfort my parents, whose money I had been wasting with great indifference. As it turned out, the money-wasting was merely an annoyance to them; their main concern, understandably, was my future.

My first paid writing job was for an alternative weekly newspaper, where I wrote music criticism. And so my parallel, independent course of study paid off somewhat, and for many years I was smug about it: I don’t have a traditional college degree and I never needed it, nah nah nah nha boo-boo! College was for amateurs, people who like to sit and talk. Working? That’s for pros. I’m a worker. I suck at sitting. That’s why I went to cooking school.

Writers sit a lot, however. Despite my deep love for alternative weeklies, I left that job and undertook a string of high-energy, low-wage positions that managed to more or less pay the bills. Chocolate factory. Cookwares store. Library. Introducing a daughter into this equation was financially irresponsible, but we did it anyway, on purpose.

Then I realized how flawed my logic was, and how pathetic and passive my budget-driven melancholy was. My husband, a likewise melancholic fellow with a meandering career background, was not going to bring home slabs of bacon, ever. I felt our lives slipping away from us as friends moved ahead into promised lands of financial security; we languished behind, tossing scraps at the incredibly persistent credit card balance we couldn’t knock out, no matter how many extra hours I picked up at whatever job I was working at the time. In order for our family to make it, I needed to become a different person, one who could gracefully eat shit. A person who could bite the bullet and follow directions she didn’t really want to follow.

•••

We don’t discuss charcuterie in chemistry. It’s an online class, which I chose because my work schedule is unpredictable. There’s a massive, poorly organized textbook, and we’re supposed to read the textbook, log in to the web portal, and take half a dozen quizzes every week. That’s it. When I emailed my instructor and asked her to recommend some resources outside of the book, she suggested I come to her lecture. “But I’m taking the class online,” I said. “The lecture is supposed to come to me.”

We do take our tests in person, and that’s when I see our instructor, who is perhaps my age, with a petite build, an awkward manner, and a head of fabulously curly blonde hair. She seems to have a genuine concern for the academic performance of her students and a genuine difficulty connecting to them conversationally. I think she’s as confident leading the class as I am taking it.

So there it is: I will probably fail the test, because instead of attending chemistry lectures after work, I’d rather rake leaves with my daughter and watch her jump in and out of the leaf piles with unmitigated three-year-old glee. I’d rather walk the dog before dinner with my husband, and we will push our daughter in the stroller with us even though she’s way too old for the stroller and has to be coaxed into it with tiny handfuls of raisins or almonds, because if my husband and I don’t move around and talk about our days in the neutral air of the outdoors, bad things will happen. I’d rather set a real table with cloth napkins and cook a real dinner, which we will sit down together to enjoy, because that’s what we do in our family. I’d rather get my proper eight hours of sleep most nights, because if I don’t, bad things happen.

Most of the kids in my chemistry lab could realistically be my kid. All these years later and I still can’t make myself care enough to pass. Or maybe I care too much. Every week that infernal textbook throws more and more concepts at us, just when the one we were covering started to get really good. If it were up to me, I’d overhaul first-year chemistry and rename it Periodic Table Studies. I love the periodic table. It’s like a beautiful map; with each examination, it reveals more intricacies, more patterns. There’s a mysticism to it, a leap of faith, because I don’t care how many experiments chemists have done over the past dozen centuries, we can’t see and touch the atoms of those elements the way we can, say, a handful of cumin seeds or a stick of butter. Or a slab of pork belly.

I spent hours making flash cards for each element, because our instructor said we’d need to memorize most of the table. My inner child leapt for joy—craft time! I wrote the Latin or Greek roots of the names, or the interesting places they were discovered, plus short descriptions of what each element looked or smelled like, so it could be more tangible. Each element had its own story. I like narratives, and so far chemistry had not given me any good ones. On the day of our second exam, I was dismayed to find we were in fact not tested on our knowledge of the periodic table, but had to fill out a long list of electron configuration problems. And yes, those do have to do with the periodic table, but not in the way I like. By the time we hurtled to those, I was still swooning over radium and rubidium.

•••

I went back to school with the ultimate goal of becoming a registered dietician. I have a culinary degree; I care about good nutrition; I love teaching cooking classes. I threw those things into a hat with my desired salary, spent a few weekends clicking away hopefully on the Occupational Outlook Handbook database, and—poof!—created my future, reasonably profitable career. The logic went like this: by the time I have my credentials, the job market for R.D.s will be extra-sweet because of the awful diets Americans have, my years of studying late into the night would pay off, and I’d be able take our family on nice vacations and finally fulfill my dream of pledging to multiple public radio stations.

I’ll be nearing fifty by then. Is it worth it? Foremost I am a chef and a writer; I intentionally cook with bacon grease and chicken fat, I use salt liberally but strategically, and I’d rather discuss how to get a good sear on a pan of mushrooms than how to best preserve their nutrient content. That many R.D.s don’t actually work with the public but create crummy, bland menus for giant institutions was something I chose to overlook.

Maybe failing chemistry is necessary. I’m stubborn, and I don’t like to accept that I can only accomplish so much in a given time frame. Those cloth napkins are one reason we have so much laundry to fold. I have quite an array. Some I purchased for a song on clearance. Some I sewed myself in the days when I did a lot of freelance writing. I thought sewing napkins was procrastinating, but it turns out it’s one of my preferred methods of prewriting. Ages have passed since I’ve made napkins, but I really enjoy using them. They make me feel especially civilized.

Using paper napkins would save me maybe a few hours of laundry chores every year, and I could use those hours to study chemistry. Instead, my pro-napkin actions have clearly voted against chemistry and all it stands for. Sometimes you can’t just dip your toe in. You have to wade up to your ankles and hang out for a while before you realize that body of water is not where you are supposed to be.

This morning, I saw my advisor so I could discuss my strategy for next semester: lighter class load, no sciences. “I am coming up on a place in my life where I won’t have the time available to excel in a demanding class the way I’d like,” I lied, because I’ve been in that place since way before I even contemplated going back to school.

My advisor suggested I take Cultural Geography to fill a requirement.

“It won’t bore me, will it?” I asked him. “Because some of my classes here have, and if I’m not engaged, I get surly and I sort of give up.”

“By showing up and doing your work during the lecture, you will get an A,” he said, which was his disguised way of confirming yes, it will bore me.

But I’m still looking forward to next semester, and the one after that. If the sad implosion of my performance in chemistry has taught me this much, what more thorny truths about myself could I discover? Class by class, I’ll wrestle with demons more terrifying and impossible than those run-of-the-mill academic ones.

I thought that understanding the reason for your past failures made you impervious to future failures of the same sort, but here I am, wrong yet again. I’ve dreamed of going back in time, armed with the knowledge of my terminally ill bank account to come, so I could excel in high school and college instead of drifting through. But now I know that I’d make the same mistakes, only with more flair. Your problems don’t go away, even when you acknowledge and accept them. They’re still there to deal with, no matter how grown-up or deserving of success you feel you may be.

You can’t just desire the result—in my case, the employment opportunities afforded by a fancy piece of paper with computer-generated calligraphy on it. You have to desire the process. There’s no point in making bacon at home if you aren’t enthralled with handling the meat, scrutinizing its progress as its flesh firms up in the dry cure, daydreaming of the savory lardons you will cut from it and fry up to top a salad of bitter greens. Making the bacon is the point; eating it is just the reward. I like learning about chemistry, but I love my family, and I can’t click pause on this part of our lives together. Chemistry wants more of me than I can give it, now or maybe ever.

I doubt I’ll go into nutrition. I’m much better at teaching people how to make pâté than I am telling them not to eat it. Wearing the costume of a future R.D. boosted my confidence a bit, but the outfit was ill-fitting. The only way I’ll ever get any kind of degree will be slowly, leisurely, the way I prefer us to eat dinner. To earn an A in my chemistry class, I’d have to rely on frozen pizzas and skip the bedtime stories I look forward to reading to my daughter. My brain and my time and my kid are too valuable to squander on half-assing anything. Maybe I’ll take chemistry twice. Not because I have to, but because I want to.

•••

SARA BIR got 68% on her latest chemistry exam and had a blast teaching her charcuterie class. Her writing has appeared in Saveur, The North Bay Bohemian, The Oregonian, and Section M. She’s currently drying a roll of pancetta in her basement and working on a vegan baking cookbook. Read more of her work at www.sarabir.com.

Follow

Follow